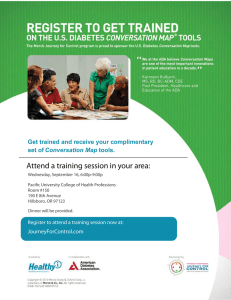

The Blue Ridge Academic Health Group Health Professions Education:

advertisement