The International Investigations Review

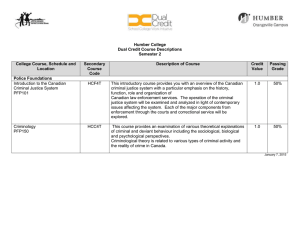

advertisement