GAO NONPROLIFERATION U.S. Agencies Have Taken Some Steps,

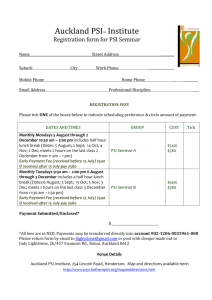

advertisement