NUCLEAR NONPROLIFERATION NNSA's Threat Assessment Process

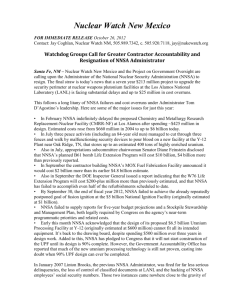

advertisement