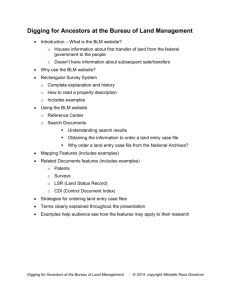

GAO URANIUM MINING Opportunities Exist to Improve Oversight of

advertisement