GAO CHEMICAL WEAPONS FEMA and Army Must

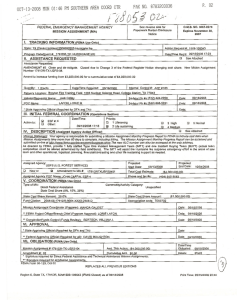

advertisement