Land Use and Remedy Selection: Experience from the Field – Kris Wernstedt

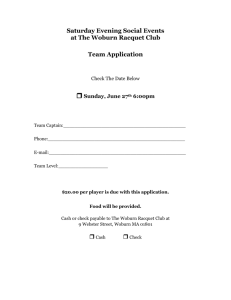

advertisement