Land Use and Remedy Selection: Experience from the Field – The

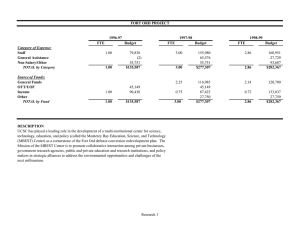

advertisement