Women and the Extreme Right: • 164

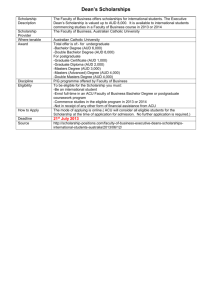

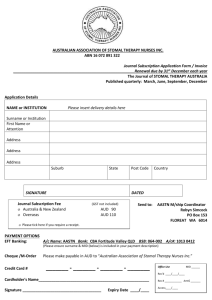

advertisement

e • 164 TERRORISM AND POLITICAL VIOLENCE - being 100 per cent ngainst immigracion’. 145. Fritt Forum, No. 1(1996). 146. According to Kathleen Uke (note 16), p.3, women in faci make racist organizations more dangerous, because they spread the ideology througb Iheir family, their personal networks and local contacts. This makes women’s inlluence often more extensive chan (be men’s. My analysis suggests thal Ihis might also hold for the Valkyrla woinen sincc. according to my observations, they have much more contact with friends ouiside the milieu than (be men do. (47. lnterview. 9 March 1996. 148. Martin Barker. The New Racism. Conservatives and the Ideology of (he Tribe (Frederick, MD: Univërsity Publications of America 1982)._ 149. Both women interviewed in Det Nye, No.l0 (Oct. 1995). 150. Det Nye, No.i0 (Oct. 1995). 151. Interview, 9 March 1996. For a discussion of the way male activists deal wiih the Holocaust, sce Fangen (note 50). (52. Kaplan and Bjørgo (note 36). 153. lnterview. 9 March 1996. Rune Gerhardsen, Labor Pany politician. Flead of Oslo Town Council. 154. Valkyrins lnstruction Manual. 155. Det Nye. No.iO (Oct. 1995). 156. Ibid. 157. Interview, 24 April 1996. 158. Fritt Forum, No.l (1996). 159. Koonz (ante 20). p450. 160. lnterview. 9 March 1996. 161. Ibid. 162. This argument was also commonly used by Nazi women in the l930s: see Koonz (note 20), p.449. 163. Jack ICjuus is the leader of Hvit Valgallianse (White Election Alliance). 164. I have desctibed the history of such views in Norway in the report ‘Rasismens historie og forhistorie (The History aud Prehistory of Racism), SFDH (Sogn og Fjordane College) report, No.1 (1993). 165. At times, tbe Women’s Klan portrayed itself as a social welfare organization. Sorne chapters collected food and money for the needy (typically K!an families), aud others ran free day-nurseries and homes for wayward giris; see Blee (note 16). p.4O. Similarly. Nazi women collecied money for poor national socialist families; see Koonz (note 20), p.463. 166. lCoonz (noce 19). 167. BIee (nole 16), p3. 168. lnterview, 24 April 1996. 169. Durham (note 37), p.279. Women and the Extreme Right: A Comment MARTIN DURHAM - Katrine Fangen’s article presents a thoughtful and well-informed account of the racist underground in Norway and the role of women within its ranks. Having achieved an impressive aceess to its activists, she gives us a portrait of a movement which, contrary to our expectations, does not simply contain men who dominate and women who accept their subordination. Instead, male activists are described as.proud that their movement contains strong women and even as contrasting their acceptance of gender equality with its rejeetion in other male-dominated subcultures.’ Nonetheless, the movement remains male-defined and in early 1995, in reaction to their secondary role, a number of women formed an all-female group. Organised in local cells, Valkyria functions as the ‘sister’ group of the Viking organisation and mns activities both with men and separately. Engaging in weapons training, involved in the inner circle directing the movement’s activities, Valkyria asserts the equal rights of women activists. But is this part of a broader trend within the international extreme right, or is this section of Norway’s extreme right an aberration within a tradition in whieh patriarchy is usually championed, not challenged? Here the article’s argumënt is tentative. The Ku Klux Klan in the l920s, Fangen notes, set up a women’s organisation which declared its support for women’s suffrage and opposed male domination. Women in the Nazi movement, she continues, were less likely to make claims of equaiity but, even in such an unpropitious environment, some were to be found who favoured an egalitarian stance. As for the modern period, neo-fascist women’s organisations exist in a number of countries but are frequently contined to being merely auxilaries of male organisätions.2 While not unique, Valkyria eertainly appears atypical and this, it is suggested, may well be linked with the national characteristics of Norway itself. According to a leading Swedish woman nazi, Norwegian NaÈism during the Second World War gave greater equality to its women activists than was the case in Sweden or Germany while today, Fangen argues, the sympatby for women’s equality among male extreme rightists demonstrates how pervasive the emancipation of women in Norway has become.3 This account raises Terrorism and Political Violeace, Vol.9, No.3 (Auwmn 1997). pp.165—lôS PUBLISHED BY FRANK CASS. LONDON i TERRORISM AND P0LITICAL V1OLENCE questions both about the distinctiveness of the Norwegian extreme right and the relationship between men and women on the extreme right more generally and it is to these that we will turn. As with the Nazis in (be past, modern extreme rightists have organised women in different ways. As part of an international skinhead subculture, Valkyria is different both in culture and age structure from tbe dominant wàmen’s organisations of the extreme right (those linked with the Front National in France and the Alleanza Nazionale, formerly the Movimento Sociale Italiano, in Italy).4 Other women’s organisations, such as the now defunct British Movement Women’s JDivision, have attempted to benefit from skinhead militancy but have tended to emphasise more ihe frequent extreme right equation of woman and family.5 The strongest comparison would seem to be with two countries referred to in the article, Germany and the United States. In Germany, as Mushaben has shown, amidst the diversity of opinion among women on the extreme iight can be founcl an insistence on equality within the movement and an impatience with assumptions of male superiority.6 This exists in different sections of the movement but of particular interest in the present context are the efforts of the Skingiri Front Deutschland and the German section of Women for Aryan Unity to oppose sexism within the neofascist skinhead subculture? As for the United States, when one skinhead-based group, the American Front, organised a women’s auxiliary, it took the name the Valkyries, while White Sisters, the newsletter of the Aryan Women’s League, also draws on an intemationally shared imagery in publishing drawings of skinhead women as ‘sword-wielding Nordic goddesses.. .fighting beside their men’.’ Similarly, the tendency for some women to be seen as mothers, some as fighters and yet others to be sexual trophies exists in all three countries, and that Valkyria activists criticise young women who play the last of these roles bears marked resemblance to the complaint of female supporters of the American Front that women they categorise as ‘sluts’ and ‘trash’ weaken the movement? Seen in this context, Valkyria may be best understood as a national manifestation of an increasingly international movement, linked by the Internet, the circulation of literature and face to face contact. How this has developed needs considerably more exploration, ideally by seholars in different countries, particularly in the light of Fangen’s references to Valkyria’s correspondence with women elsewhere and the presence ofsome of them at its camps (and, we might add, the attendance of the Norwegian group at the 1995 Rudolf Fless commemoration march in Gerrnany))° Among Norwegian racist skinheads, as with their counterparts in Germany, an ongoing dispute encompasses positions which range from female assertion to attempts to exclude women altogether.” The characteristics of Norwegian society, of particular youth cultures and of WOMEN AND TIIE EXTREME RIGHT 167 underground organisation all bring their imperatives, and debates in other strands of the Norwegian extreme right and in the extreme right in other countries will differ in important ways. But there are also common strands. In Britain, for instance, during the I 980s, an activist in one wing of the National Front, Jackie Griffin, argued that women should play a greater role in the movement while a member of the other wing, Caralyn Taylor, declared upon her election to the organisation’s National Directorate that women had ‘been brainwashed by male members into thinking that running the National Front is a “job for the boys”.’ Even the British National Party, led by the enthusiastically patriarchal former NF Chairman, John Tyndall, has published an articie in which a woman activist denounced male chauvinism and called for the organisation to prove itself to be one ‘of roughly equal rights’.” In recent years, amidst the National Front’s continued fragmentation and crisis in the British National Party, racist organisers have worked among skinheads in an effort to create an overtly National Socialist grouping. Overwhelmingly male, in these circles too tensions have been evident in the emergence of a Patriotic Women’s League whose newsletter, Valkyrie, declares its wish to emulate women’s organisations in America. Calling for women to ‘ride by the White man’s side and sing the racial song’, il also suggests that ‘our views’ might ‘in some cases. .differ from those of our menfolk’. One area ofespecial importance, it continued, was that of violence towards women.’3 In a number of countries and increasingly internationally, a burgeoning racist skinhead network has shifted the balance of forces between different strands of the extreme right. Such networks rarely display patience with the electoral strategy of established organisations, favouring instead a street politics which frequently takes the form of physical violence. Fangen’s articie shows a hitherto largely unexplored dimension of this movement in arguing that rather than simply exaggerating the machismo of fascismo, it is also developing a strong female role for some of its militants. At times, this argument can be contested; to claim, for instance, that an anti-pornography stance evidences a female agenda is problematic in light of the common ideological opposition to the sex industry of extreme right organisations as a whole.’4 But while not always agreeing with its argument, anyone concerned with the issue of women’s role in the extreme right will find this account both fascinating in its material and fundamental in the questions it raises and the avenues of inquiry it suggests. . NOTES I. KaLtine Fangen, ‘Separate or Equal? The Emergence of an All-Female Group in Norway’s Rightist Underground’. Terrorisni andPolirical Violence 9/3 (Autuma 1997) p143. 2. Fangen (note I) pp.l25—7. — TERRORISM AND POLITICAL VIOLENCE 168 3: Fangen (nole 1) pp.l30. 160. 156. 4. Italy has not been well served in the exisling literature but for a discussion of different strands on the French exlreme right. see Fiammetla Venner, ‘Le militantisme féminin d’extréme droite: “Une autrc manièrt d’étre féministe” V. French Politics aud Sociery 11/2 (Spring 1993) pp.33—54. 5. For women in Ihe British Movement. see Veronica Ware; Women and fire National Front (Birmingham: Searchlight, n.d.. c1978) pp.l6—lB; Britons in Revolt (Deeside: British Movement 1980). 6. Joyce Marie Mushaben. ‘The Rise of Femi-Nazis? Female Participation in Right-Extremist Moveineots In Unified Germany’, paper prepared for presentation at the Annual Meeling of che American Political Science Associationr Chicago, 1995. A revised version appears in Gernian Polities 5/2 (Aug. 1996) pp.24O—6l. 7. ‘Frauen in der faschistischen Skinheadszene’. Antifa-Info. Mai—iune 1993. 8. ‘/illage Voice. 28 April 1992; Klanwatch Intelligence Report, June 1991 reproduced in Procreating White Suprernacy: Wonren aud lite Far Rigirt (Atlanta: Center for Democratic Renewal 1996). 9. Fangen (note I) pp.l49—SO; Village Voice (note 8). 10. Fangen (nole I) pp.l’48. 146; Searchliglrt. Oct. 1995. Il. Fangen (note I) pp.I4O—4l; see Antifa-lnfr (Note 7) re ;he Anti Frauen Organisation in Germany. 12.: Martin Durhani. ‘Women and the British Extreme Right’. in L. Cheles et at (eds). The Far Righi in Western aud Fastern Europe (London: Longman 1995) pp.2&l, 282. 285. 13. Valkyrie, I. nd.. c1995. 14. Fangen (nole I), pp.l45. 154—5. Book Reviews Mbrdechai Bar-On, In Pursuit of Peace: A History of the Israeli Peace Movement, Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press, 1996. Pp.470. biblio. ISBN 1-878379-53-4. Mordechai Bar-On has writtên an overview of the Israeli peace movement from the birth of the Slate in 1948 up to the Rabin—Arafat handshake on the White House lawn in September 1993. li is therefore essentially a well-researched chronological record — a documentation rather than an analysis. It is also an account of how both the nationalist dreams of Eretz Israel and Filastin had to be compromised such that both peoples could attempt to share the land in peace. To outsiders this may seem a self evident solution that should have been agreed long ago, hat those in the grip ofconflict would argue that iL was clearly a matter of survival. The kar of the ‘other’ overrode all other preoccupations. Jews as well as Palestinians have become the prisoners of their history and sometimes the perpeLratorS of historical myth. Even 50, two thousand years of Jewish existence at history’s margins as civilisation’s scapegoat was a psyehological baggage which could not be disposed of overnight. Add to this, both Arab rejection of partition and the Jewish desire to create a homeland in 1920 (San Remo Conference), 1921 «be separation ofTrans-Jordan), 1937 (Royal Commission), 1947 (UN Resolution) as well as the isolation and murder of the Jews in the Holocaust — aud the barrier towards even the môst elementary dialogue became insurmountable. This conjunction of events would have tested even the most rational and moderate of lsraelis in locating a pathway through the morass of emotions and suffering to establish a dialogue with Palestinian partners. Through the declassification and opening of state archives in the 1980s, lsraeli writers such as Benny Morris have indicated that there were groups, often centred around the leftist Zionist party Mapam which .wished to entertain a peace option both during and in the aftennath of the war of independence in 1948, in government and in the military. Significantly, an Israeli Peace Committee composed of’ Mapam leaders, members of the Communist Party and several intellectuals was formed in 1949. lt was essentially a mouthpiece for the Sovjet controlled World Peace Council and therefore its causes were cold war neutrality, stopping German reannament and banning nuclear weapons. The pertinent issue of ending the Israeli—Arab confrontation was unceremoniously circumvented. As Bar-On comments, it was psychologically too sensitive and too controversial a proposition for Jsraelis to contemplate at a time of state-building. By 1948. Ben-Gurion had effectively come round to accepting the position which his Revisionist rival, Vladimir Jabotinsky. bad stipulated in his famous article The Iron Wall over a guarter of a century previously in that there was an intrinsic contradiction between Arab and Israeli interests. Yet Ben-Gurion’s more strident policies were sometimes opposed by his Foreign Minister and later his temporary replacement as Prime Minister, Moshe Sharett. Peace, however, at that time in the 1950s was an illusion. As Bar-On remarks ‘Sharett, Mapam and the other moderates could at most present a pious conviction that by refraining from aggravating the conflict through aggressive initiatives, Israel might lay the foundation for reconciliation sometime in the remote aud forseeable future.’ The shedding of the Stalinist era forced many leftist