Document 11436808

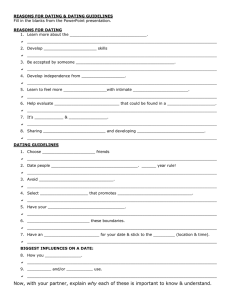

advertisement