THE BUSINESS CASE FOR MANAGING ROAD RISK AT

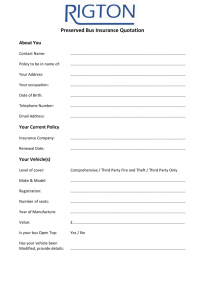

advertisement