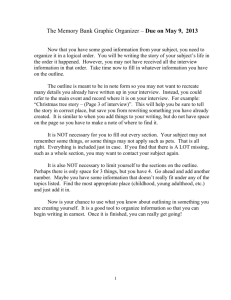

From Generation to Generation:

advertisement