Environment and Behavior

http://eab.sagepub.com

Predictors of Ideas about Seasonal Psychological Fluctuations

Tim Brennen, Catherine Hall, Bas Verplanken and Julia Nunn

Environment and Behavior 2005; 37; 220

DOI: 10.1177/0013916504269648

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://eab.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/37/2/220

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Environmental Design Research Association

Additional services and information for Environment and Behavior can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://eab.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://eab.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations (this article cites 24 articles hosted on the

SAGE Journals Online and HighWire Press platforms):

http://eab.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/37/2/220#BIBL

Downloaded from http://eab.sagepub.com at OSLO UNIV on February 13, 2007

© 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

ENVIRONMENT

10.1177/0013916504269648

Brennen

et al. / SEASONAL

AND BEHA

PSYCHOLOGICAL

VIOR / March 2005

FLUCTUATIONS

PREDICTORS OF IDEAS ABOUT

SEASONAL PSYCHOLOGICAL

FLUCTUATIONS

TIM BRENNEN is professor of cognitive psychology at the University of Oslo, Norway. His studies of cognition over the annual cycle are an example of his interest in

applied and theoretical aspects of cognitive psychology.

CATHERINE HALL participated in this study as part of her psychology degree at

Goldsmiths College, University of London. She is now studying for her degree in medicine at the University of Newcastle.

BAS VERPLANKEN is professor of social psychology at the University of Tromsø,

Norway. His main research interests are attitude-behavior relationships, consumer

behavior, health behavior, and decision making.

JULIA NUNN is senior lecturer in the Department of Psychology, Goldsmiths College, University of London. Her main research interest is the cognitive neuroscience

of memory.

ABSTRACT: This article reports a study of attitudes and beliefs about seasonal psychological cycles in a sample of 160 people living in London. Participants rated their

perceptions of seasonal fluctuations on cognitive, emotional, physical, and social

functioning in themselves, in others at the same latitude, and in the Arctic population

by means of the Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire and a specially designed

questionnaire. They also completed a test of astronomical knowledge, a test of knowledge about seasonal affective disorder, and an instrument measuring the Big Five personality dimensions. Seasonal mood swings correlated positively with SAD

knowledge and extraversion and negatively with the respondents’ emotional stability

and knowledge of astronomy. Perception of seasonal change in others appeared to be

mediated by their perceptions of their own seasonal fluctuations. Generally, participants did not have unwarranted negative predictions about the impact of the annual

cycle on psychological swings in the Arctic.

Keywords:

seasons; psychological functioning; seasonal affective disorder; Arctic; personality

ENVIRONMENT AND BEHAVIOR, Vol. 37 No. 2, March 2005 220-236

DOI: 10.1177/0013916504269648

© 2005 Sage Publications

220

Downloaded from http://eab.sagepub.com at OSLO UNIV on February 13, 2007

© 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Brennen et al. / SEASONAL PSYCHOLOGICAL FLUCTUATIONS 221

First, some facts: The Earth makes a full revolution on its axis once a day,

and the angle at which it rotates is tilted by 23.5 degrees relative to the perpendicular of its orbit around the sun. The Earth orbits the sun every

365.2422 days (Kaler, 1994). These facts in combination give rise to the different seasons on Earth by causing differences in day length over the annual

cycle. Between the spring and the autumn equinox, places in the northern

hemisphere have more day than night, whereas between the autumn and the

spring equinox they have more night than day, and the converse is true for

places in the southern hemisphere. Furthermore, the farther a place is from

the equator the more extremely the light conditions vary over the annual

cycle, culminating in the fact that at the North and South Poles, each annual

cycle consists of 6 months of daylight followed by 6 months with the sun

below the horizon. From March to September, there is daylight at the North

Pole; from September to March, there is daylight at the South Pole.

These astronomical facts are relevant to the present study in two ways, as

will become evident below. First, the changes in day length are presumed to

have effects on psychological functioning. Modern psychiatry describes a

condition known as seasonal affective disorder (SAD). Individuals with SAD

have recurrent episodes of depression occurring during winter, with complete remission of the symptoms in summer. The initial report from

Rosenthal et al. (1984) aroused great interest, and there has since been published upwards of 1,000 articles on the topic. Much less research has investigated cognitive swings over the annual cycle (see Brennen, 2001; Brennen,

Martinussen, Hansen, & Hjemdal, 1999; Taylor & Duncum, 1987).

In the present study, a sample of participants living in London, at 51

degrees north, was asked about the seasonal fluctuations in psychological

functioning that they themselves experience as well as about their intuitions

about what other people living at the same latitude experience and about what

people living north of the Arctic Circle (66.5 degrees north) experience. The

study also investigated what other beliefs and knowledge states are associated with beliefs about seasonal psychological fluctuations. Specifically, a

questionnaire was devised to test participants on their grasp of facts about the

solar system.

PSYCHOLOGY AND THE SEASONS

SAD

According to DSM-IV criteria, to qualify for a diagnosis of SAD, sufferers must demonstrate a clear association between the onset of major

Downloaded from http://eab.sagepub.com at OSLO UNIV on February 13, 2007

© 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

222 ENVIRONMENT AND BEHAVIOR / March 2005

depression at a regular and particular time of year, show remission of symptoms at a characteristic time of year, have had at least two episodes that have

occurred at the same time of year, and the seasonal depressive episodes must

outnumber the nonseasonal episodes of depression that may have occurred in

an individual’s lifetime. Although the majority report such episodes of

depression occurring during the winter months, SAD is also reported to

occur in the summer, but it is much less common.

Since the discovery of SAD, a milder form has been identified. Labelled

subsyndromal SAD (S-SAD) by Kasper, Rogers, et al. (1989) and winter

blues by Rosenthal (1998), this milder form is diagnosed when individuals

report seasonal changes in mood that cause mild dysfunction and vegetative

symptoms similar to SAD but below the level of clinical significance. More

generally, the tendency to experience seasonal swings in mood and behavior

is called seasonality.

Even people who do not qualify for the criteria for S-SAD report changes

in mood in winter. For instance, Kasper, Wehr, Bartko, Gaist, and Rosenthal

(1989) reported that in the United States, 92% of their sample reported seasonal fluctuations in mood and behavior. Therefore, seasonal mood fluctuations can be thought of as a dimension, with those suffering from SAD at one

end and those experiencing no seasonal changes at the other end, with S-SAD

between the two extremes (Kasper, Rogers, et al., 1989).

PREVALENCE OF SAD

Estimates of SAD prevalence vary from 0% to 15% among studies, and

this may be due to methodological differences between studies. The disorder

appears less prevalent among 20-year-olds and 50-year-olds than among

those at ages in between (Booker & Hellekson, 1992; Eagles et al., 1999).

Women have a higher incidence of SAD (Hodges & Marks, 1998; Kane &

Lowis, 1999; Lee & Chan, 1998; Magnusson & Stefansson, 1993; cf. Han

et al., 2000).

LATITUDE AND MOOD

The fact that human mood can fluctuate in response to the seasons has

indicated that this specific affective disorder may have a biological etiology

and could be a physiological response to the reduction in the amount of daylight, possibly by disturbing circadian rhythms in melatonin release

(Schlager, 2001; Thompson & Isaacs, 1988). If light is the underlying cause

of SAD, one would expect that higher latitudes, which get less daylight in

winter, would be associated with higher prevalence of SAD. A large study by

Downloaded from http://eab.sagepub.com at OSLO UNIV on February 13, 2007

© 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Brennen et al. / SEASONAL PSYCHOLOGICAL FLUCTUATIONS 223

Rosen et al. (1990) examined the relationship between prevalence of SAD

and latitude in the United States. At four latitudes ranging from 27 degrees

north to 42.5 degrees north, prevalence ranged from 1.4% to 9.7%, and the

correlation between prevalence and latitude was .11. As the authors acknowledge, the sampling procedure may overestimate SAD incidence and, in any

case, the association is weak.

Recent reviews of the studies of the association between SAD prevalence

and latitude show an overall correlation of .001 (Mersch, 2001; Mersch,

Middendorp, Bouhuys, Beersma, & van den Hoofdakker, 1999b). Furthermore, Europe, most of which is north of the United States, has a significantly

lower mean prevalence. However, within Europe and the United States separately, there were positive correlations of 0.54 and 0.9, respectively. This

shows there must be many factors more important than latitude in determining SAD prevalence.

Hansen, Jacobsen, and Husby (1991) showed that living at a very northerly latitude does not necessarily lead to a high prevalence of mood problems.

They tested about 50% of the population living in Tromsø (69 degrees north),

a sample of over 7,000 people, and found few problems with sleeping, mood,

and coping in the middle of winter. Only 7% of participants reported more

than one of these being a problem.

Over the past 4 decades, the psychosocial well-being of scientists and support staff living for the winter months on research stations on Antarctica has

been closely monitored (Suedfeld & Weiss, 2000). A simple interpretation of

the latitude hypothesis would be that SAD symptoms should be widespread

among these groups. This was only partially confirmed by Palinkas, Houseal,

and Rosenthal (1996) who examined the relationship between mood fluctuations and latitude prospectively in a clinically normal group of 70 men and

women with no history of SAD who spent the winter on Antarctica. The prevalence of S-SAD increased from 10% to 30% over the winter; however, only

one case of SAD was reported. Furthermore, Palinkas and Houseal (2000)

described the seasonal changes in mood of workers at Antarctic research stations in stages of challenge, accomplishment, and exhaustion, which has a

qualitatively different feel to the symptomatology of SAD.

There is evidence, however, that winters at high latitude cause a variety of

sleep-related problems. Studies in the north of Norway and on Svalbard, at 80

degrees north, have demonstrated the occurrence of insomnia, an inability to

fall asleep, repeated waking during the night, and the lack of feeling rested in

the morning (Husby & Lingjærde, 1990; Nilssen et al., 1997). Similarly, for

eating problems, the dark polar winter appears to cause eating disturbances in

a significant proportion of the population at high latitude, with a common

Downloaded from http://eab.sagepub.com at OSLO UNIV on February 13, 2007

© 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

224 ENVIRONMENT AND BEHAVIOR / March 2005

symptom being overeating of carbohydrates (e.g., Perry, Silvera,

Rosenvinge, Neilands, & Holte, 2001).

LATITUDE AND COGNITION

There has been relatively little examination of the effects of the seasons on

cognition in normal individuals. Taylor and Duncum (1987) reported that,

among a sample spending the winter in Antarctica, there were no observed

deficits on objective tests of cognitive performance, although there were selfreports of mental sluggishness. Brennen, Martinussen, Hansen, and Hjemdal

(1999) investigated whether cognition was cyclical in a nonclinical sample

living at 69 degrees north, testing participants both in summer and winter on a

wide range of cognitive tasks that included verbal memory, attention, and

reaction times. They found that people actually demonstrated winter advantages in four of the tests and a winter disadvantage in only one test. Also,

Brennen (2001) showed that these results were independent of gender and

the proportion of one’s life lived in northern Norway. Furthermore, the four

winter advantages were for simple online attentional processing tasks, with

very little memory load. Therefore, the best current conclusion is that memory processing does not have an annual rhythm in normal individuals,

whereas attentional processing has a weak annual rhythm, with an advantage

in winter.

SEASONALITY AND PERSONALITY

Murray, Hay, and Armstrong (1995) were the first to look for steady internal individual differences that may be associated with seasonality. With a

sample of 258 Australian female twins, they found that self-reports of seasonality correlated positively with neuroticism. On the other hand, Gordon,

Keel, Hardin, and Rosenthal (1999) administered a personality questionnaire

to a sample of 45 SAD patients and found that neuroticism did not correlate

with seasonality. However, by testing SAD patients, they restricted the range

of seasonality to the upper end of the scale, thereby reducing the chances of

finding a link between neuroticism and seasonality. In the present study, we

also administered a personality questionnaire to our respondents to shed

some light on this issue. The present sample is not selected on the basis of

seasonality, and so on the basis of Murray et al.’s (1995) results, we predicted

a negative association between seasonality and emotional stability (a factor

that, in the questionnaire used here, is the converse of neuroticism).

In sum, research on the psychology of high latitudes has produced counterintuitive evidence. There is at best weak evidence for a correlation of SAD

Downloaded from http://eab.sagepub.com at OSLO UNIV on February 13, 2007

© 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Brennen et al. / SEASONAL PSYCHOLOGICAL FLUCTUATIONS 225

with latitude, and the vast majority of people living in polar regions have no

serious problems with mood in winter. In terms of cognitive performance, the

little available evidence suggests that cognition may be sharper in winter. On

the other hand, sleeplessness is a common problem in the winter months at

high latitudes.

THE PRESENT STUDY

Widespread incorrect negative intuitions about polar life can have pejorative economic consequences for the Arctic. Businesses may be less inclined

to invest, tourists may be unduly reluctant to visit, and, because no capital cities are located in the polar regions, residents of the Arctic may suffer from

underinvestment as a result of distorted, incorrect beliefs among decision

makers. An inappropriate belief that latitude correlates strongly with SAD

prevalence tends to give a clinical diagnosis to a whole region, which is

nontrivial considering that it is estimated that, worldwide, over 2 million people live north of the Arctic Circle. Consequently, it would be interesting to

explore individual beliefs and perceptions about the effects of the annual

changes on human performance.

The present study investigated participants’ experience of seasonal

swings in a range of cognitive, mood-related, and everyday behaviors. It

explored the concept of seasonality by asking participants also to estimate

what sort of seasonal swings are experienced by other people at the same latitude (51 degrees north) and by people living in the Arctic Circle (north of

66.5 degrees north). Furthermore, and this is where we come to the second

use we make of the astronomical facts in the opening paragraph, we have

noted informally that many people do not possess knowledge of basic facts

about the solar system. In the absence of a firm grasp of astronomical knowledge, seasonal changes may seem more capricious, and this study investigated astronomical knowledge to see what relationship, if any, it has with

beliefs about the psychology of the seasons. It is known that during the first

years of schooling, children tend to offer an explanation of the day-night

cycle consistent with their knowledge derived through observation that the

sun and moon are above the Earth, that their movements cause day and night,

and that the Earth is flat. Later, as they are taught the Copernican model of the

Earth rotating around the sun, children’s explanations seem to be based on a

combination of their intuitive model and the scientific one, and this occurs by

the age of 11 or before (Diakidoy, Vosniadou, & Hawks, 1997; Roald &

Mikalsen, 2001; Vosniadou & Brewer, 1992, 1994). The present study tested

adults’ grasp of the implications of the Copernican model for Earth in

conjunction with the Earth’s axis being at an angle to the path of the orbit.

Downloaded from http://eab.sagepub.com at OSLO UNIV on February 13, 2007

© 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

226 ENVIRONMENT AND BEHAVIOR / March 2005

METHOD

PARTICIPANTS

One hundred and sixty people participated in this study, which was conducted between October and December, 2000. Participants were drawn from

among undergraduate psychology students at Goldsmiths College, University of London, who took part to gain credits as part of their first-year undergraduate course requirements. Participants were also recruited from the

general population of London. Their age ranged from 18 to 87, with a mean

age of 31.9 (SD = 15.3); 47 were male (mean age = 39.4, SD = 17.1), and 113

were female (mean age = 28.7, SD = 13.3).

PROCEDURE

The undergraduate psychology students were recruited using posters

advertising the study on the university campus. The posters provided basic

details about the study, including that it was an investigation of mood and

cognition, and invited interested participants to sign up for one of the available time slots and to meet the researcher in a quiet room situated on the

university campus.

Before being asked for written consent, all participants were then told that

the study would take about 45 minutes in total, that all information would be

treated confidentially, and that they could withdraw from the study at any

stage. They were then instructed to complete the battery of tests in the following order: Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire, followed by the Cognition, SAD, and Astronomy Questionnaire, and then the personality

questionnaire. On completion of the questionnaires, participants were fully

debriefed and given an information sheet giving an outline of the study, background information, and references for further information on the topic area.

The remaining participants were recruited in public places in London, and

questionnaires were either distributed by hand or sent out in packs with

instructions on the order in which to complete them. Most of these questionnaires were not filled in immediately but were handed back later in person or

sent back in the post. On receipt of the questionnaires, these participants were

either debriefed in person or via e-mail.

PSYCHOMETRICS

The battery of tests consisted of the Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire, a personality questionnaire, and two questionnaires developed for

Downloaded from http://eab.sagepub.com at OSLO UNIV on February 13, 2007

© 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Brennen et al. / SEASONAL PSYCHOLOGICAL FLUCTUATIONS 227

this study that were specifically designed to look at annual seasonal psychological rhythms in self and others and to tap basic knowledge about the solar

system.

Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire. The Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire (Rosenthal et al., 1984) is a widely used instrument that

can be self-administered and that retrospectively evaluates over the course of

a year at what time people feel at their worst and best, the degree to which

such changes are perceived a problem, changes in dietary and sleep patterns,

and the extent of seasonal variation in mood, appetite, weight, sleep, energy,

and socialization. These six latter scales provide the Global Seasonality

Score (GSS), ranging from 0 to 24: the higher the score, the greater the degree

of seasonal change. Rosenthal’s (1998) version of the Seasonal Pattern

Assessment Questionnaire was used in this study.

Seasonal psychological changes in self and others. We compiled a questionnaire to examine seasonal psychological changes in the sample in

domains such as cognitive, emotional, physical, and social functioning. It

also examined beliefs about the effect of the seasons on the functioning of

others living in London and of people living in the Arctic.

For each attribute, participants were asked whether they noticed any seasonal changes (no change, slight change, moderate change, marked change,

extremely marked change), at what time of the year the change occurred, and

if it was a positive or negative change.

Knowledge of SAD. The next part of the questionnaire consisted of

multiple-choice questions and assessed participants’ knowledge of SAD.

SAD knowledge was calculated by the number of correct responses to these

questions, and each respondent was given a score out of five.

Knowledge of astronomy. The final part of the questionnaire consisted of

10 multiple-choice questions about astronomical knowledge, with the correct answer and three distracters. More specifically, the questions tested

knowledge of the relationship between the Earth, the sun, and the seasons.

Astronomical score was calculated by the number of correct responses out

of ten.

The Five Factor Personality Inventory (FFPI). The FFPI consists of 100

questions shown to measure five personality dimensions: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and autonomy. Each scale

appears to be stable, valid, and internally consistent (Goldberg, 1990;

Downloaded from http://eab.sagepub.com at OSLO UNIV on February 13, 2007

© 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

228 ENVIRONMENT AND BEHAVIOR / March 2005

Hendriks, Hofstee, & de Raad, 1999). This instrument consists of 100 items.

Respondents rate on 5-point scales the degree to which each is applicable to

them, and each of the five personality dimensions is measured by 20 items.

RESULTS

DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS

The sample’s education level and occupation status are presented in

Table 1.

PREVALENCE OF SAD, S-SAD, AND GSS

Using Kasper, Rogers, et al.’s (1989) and Kasper, Wehr, et al.’s (1989) criteria, the proportion of participants with SAD was 4.4%, made up of 6

females and 1 male. A further 24 (15%) had S-SAD, a group that was composed of 4 males (9%) and 20 females (18%). The remaining 129 (81%) did

not report problematic seasonal changes, and there was no report of summer

SAD. Diagnosis by questionnaire may well lead to overestimation of SAD

rates, and on the basis of these prevalence data, we wish only to claim that this

sample is within normal range of what might be expected in a general

population.

Although seasonality appeared stronger in women, a chi-square test

revealed no significant gender differences in SAD status, χ2(2) = 3.27, p =

.195. Of those qualifying for a diagnosis of SAD, the mean age was 37.86

(SD = 13.2), and the mean age for S-SAD was 28.33 (SD = 9.2).

The mean overall GSS was 9.23 (Range = 1-24, SD = 5.1). This figure is

higher than previous studies in Britain and similar latitudes (e.g., Eagles,

Mercer, Boshier, & Jamieson, 1996; Mersch, Middendorp, Bouhuys,

Beersma, & van den Hoofdakker, 1999a), where the mean GSSs were just

under 6. As found previously (e.g., Eagles et al., 1996), females (M = 10.5,

SD = 4.7) scored significantly higher than did males (M = 6.3, SD = 4.8,

t(158) = 5.06, p < .001).

KNOWLEDGE OF SAD

Affirmative responses were received from 134 (84%) of respondents to

the following question: “Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) may be a subtype of depression in which individuals feel depressed in the winter, but

Downloaded from http://eab.sagepub.com at OSLO UNIV on February 13, 2007

© 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Brennen et al. / SEASONAL PSYCHOLOGICAL FLUCTUATIONS 229

TABLE 1

Participant Demographics

Demographic

Education level

No formal qualifications

Left school at 16

Left school at 18

University graduate

Postgraduate degree

Occupation status

Unemployed

Retired

Student

Housewife

Semiskilled

Skilled

Intermediate

Professional

%

2

8

47

38

6

0.6

4

44

4

9

6

8

23

recover in the spring and summer. Have you heard of this disorder?” Females

(88%) were more likely to have heard of the disorder than were males (72%),

t(158) = 2.2, p < .029. There was general uncertainty about the underlying

etiology of the disorder. Of the 26 people who had not heard of the disorder,

half did not hazard a guess at the possible cause of SAD, and only 6 (23%)

said it might be to do with light. Among those who had heard of it, 86 (64%)

mentioned changes in the amount of sunlight and only 15 (11%) did not speculate about a cause. In line with the (limited) support for the latitude hypothesis, the majority of the sample identified that winter SAD would be less of a

problem for those living at the equator (78%) and a greater problem for people living close to the North Pole (70%). Most of the sample correctly

reported that women were more likely to suffer from the disorder (60%), with

36% guessing no difference between the sexes and with 4% guessing that

men suffered more. Only 28% of the sample thought that people under 40

would suffer most from SAD, which is what the scientific literature in fact

suggests, whereas 41% of the sample incorrectly believed that SAD was

equally prevalent among all age groups. Finally, whereas 43% thought that

SAD was a medical disorder, a fairly large proportion (30%) believed it was a

social construction.

Individuals’ SAD knowledge was calculated on their correct response to

the five questions about SAD. The mean score for SAD knowledge was 3.02

Downloaded from http://eab.sagepub.com at OSLO UNIV on February 13, 2007

© 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

230 ENVIRONMENT AND BEHAVIOR / March 2005

(SD = 1.2). Females (M = 3.2, SD = 1.1) were more knowledgeable of the

basic facts of SAD than were males (M = 2.7, SD = 1.3, t[158] = 2.23, p <

.027).

KNOWLEDGE OF ASTRONOMY

Individuals’ astronomical scores were calculated on their correct

responses to the 10 remaining questions. The mean astronomical score, with

chance giving an expected score of 2.5 out of 10, was 6.82 (SD = 2.3, range 110), with females (M = 6.32, SD = 2.2) demonstrating less knowledge of

astronomy than males (M = 8.02, SD = 2.0, t[158] = 4.59, p < .001).

The majority of participants correctly identified that (a) in England the

length of days and nights are roughly the same during spring and autumn

(71%); (b) the Earth rotating on its axis is responsible for day and night

(67%); (c) it takes a year for the Earth to revolve around the sun (70%); (d) in

summer the North Pole receives daylight 24 hours a day (64%); (e) the 21st of

June is the shortest day in Australia (71%); (f) Australia is in the southern

hemisphere (93%); (g) London is 51 degrees north rather than east, south, or

west (60%); (h) midnight sun would mean there would be daylight 24 hours a

day (71%); and during the two winter months in northern Norway there

would be some daylight around noon (64%). Only 51% correctly identified

that days and nights at the equator are of approximately the same length.

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN GSS, ASTRONOMICAL KNOWLEDGE,

SAD KNOWLEDGE, PERSONALITY, AND EDUCATIONAL LEVEL

Knowledge of SAD was positively correlated with GSS (r = 0.21, p <

.007), and this relationship remained significant when controlling for education (r = 0.19, p < .014). The Pearson correlation coefficient revealed a small

but significant association between SAD knowledge and SAD status (r =

0.158, p < .047). Furthermore, the level of educational attainment was positively correlated with SAD knowledge, indicating that those with greater

educational attainments had a greater knowledge of SAD (r = 0.157, p <

.047).

The amount of astronomical knowledge was positively correlated with

educational achievements (r = .21, p < .001). There was no significant relationship between SAD status per se and astronomical knowledge (r = 0.07,

p > .1), but GSS was negatively correlated with level of astronomical knowledge (r = –0.16, p < .038). The mean GSS for the 20 people who got all the

astronomical questions correct was 7.2 (SD = 4.5). The mean GSS for the 14

people scoring 1, 2, or 3 on the test was 11.1 (SD = 2.9). Correct answers on 9

Downloaded from http://eab.sagepub.com at OSLO UNIV on February 13, 2007

© 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Brennen et al. / SEASONAL PSYCHOLOGICAL FLUCTUATIONS 231

out of the 10 astronomical questions correlated negatively with GSS, whereas the other only correlated +0.02.

There was no relationship between GSS and educational level (r = –0.11,

p = 0.181). SAD knowledge and astronomical knowledge were positively

correlated (r = 0.22, p < .02). Controlling for education, the relationship

remained significant (r = 0.19, p < .05).

To further explore the relationship among astronomical knowledge, SAD

knowledge, and GSS, a multiple regression analysis was conducted. With

education held constant, SAD knowledge was a significant predictor of GSS,

t(2, 157) = 2.74, p < .01, explaining 4% of the variance in GSS. Adding astronomical knowledge increased the variance explained to 7%, F(3, 156) = 2.48,

p < .05.

For each participant, a score on the five personality dimensions measured

by the FFPI (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and autonomy) were calculated and then correlated with GSS. There

was a significant negative correlation between emotional stability and GSS

(r = –.19, p < .02) and a positive correlation between extraversion and GSS

(r = .19, p < .02).

PERCEPTION OF CHANGE IN PSYCHOLOGICAL FUNCTION IN SELF,

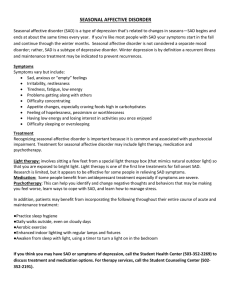

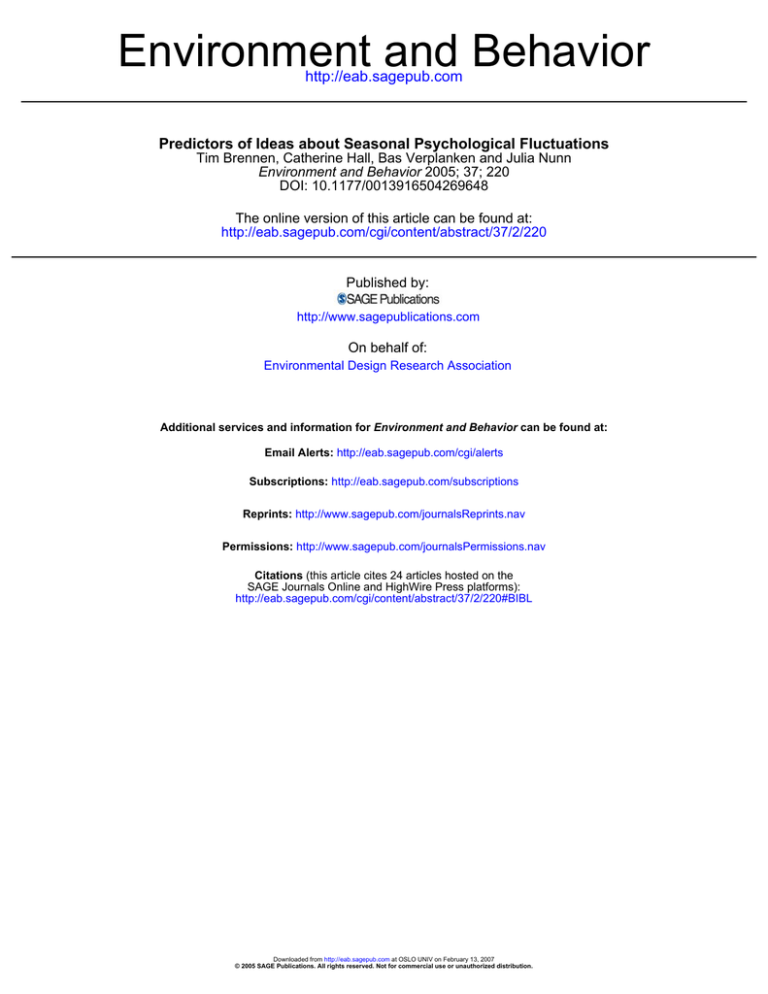

OTHERS IN ENGLAND, AND OTHERS IN THE ARCTIC CIRCLE

Very few times did a participant claim annual variation in any attribute

was other than slight or moderate. Separately for SAD-related attributes and

cognitive attributes, Figure 1 presents a summary of the proportion of participants reporting no change and winter or summer advantages for themselves,

for other Londoners, and for Arctic dwellers, collapsing over slight and

moderate responses.

For each of the three scales, alpha coefficients were calculated. To use

scales of sufficient reliability, three items (general appetite, consumption of

alcohol, and consumption of drugs) were excluded. The alpha coefficients

for the resulting three scales were as follows: self = 0.72, other Londoners =

0.70, Arctic = 0.76.

Correlations were calculated between perceptions of change in oneself

and perceptions of change in other people living in London and the Arctic.

Pearson correlation coefficients revealed significant relationships between

self and others in England (r = 0.412, p < .001), between self and those in the

Arctic (r = 0.312, p < .001), and between others in England and the Arctic (r =

0.475, p < .001).

The three conditions for mediation were satisfied (Baron & Kenny, 1986),

and so a mediation analysis was conducted to gain a more precise picture of

Downloaded from http://eab.sagepub.com at OSLO UNIV on February 13, 2007

© 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

232 ENVIRONMENT AND BEHAVIOR / March 2005

100

80

60

% of sample

40

No change

20

Summer advantage

Winter advantage

0

ic

ct

Ar

D

s

er

SA

on

nd

Lo

D

SA

lf

se

D

tic

SA

rc

A

s

ve

er

iti

on

gn

nd

co

Lo

ve

iti

gn

co

lf

se

ve

iti

gn

co

Figure 1: The Percentages of Participants Rating No Change or a Seasonal

Advantage on Cognitive and SAD-Related Dimensions in Themselves,

Other Londoners, and People Living in the Arctic

the relationship of self perceptions and perceptions of others on the perception of Arctic people. We hypothesized that perception of others would mediate the relation between self-perception and perception of Arctic people.

There were significant relationships between self-perception and perception of Arctic people (the criterion) and self-perception and perception of

others (the mediator). Regressing perception of Arctic people on both selfperceptions and perception of others yielded a nonsignificant beta for selfperceptions (β =.14, t = 1.8, p > .05) and a significant beta for perceptions of

others, (β =.42, t = 5.4, p < .05). Therefore, in this sample, respondents based

their ideas about those in the Arctic primarily on how they think other people

in England are affected by the seasons, which is again based on how they

themselves are affected.

DISCUSSION

This study explored participants’ reports of seasonal psychological fluctuations and their personality, their knowledge of SAD, and their knowledge

of basic astronomy. The results demonstrated links among seasonality,

Downloaded from http://eab.sagepub.com at OSLO UNIV on February 13, 2007

© 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Brennen et al. / SEASONAL PSYCHOLOGICAL FLUCTUATIONS 233

personality, and knowledge of SAD and astronomy. They also showed that

people retain inaccurate beliefs about the physical environment and its potential effect on human functioning.

Performance on the test of astronomical knowledge correlated negatively

with GSS, which raises the interesting possibility that knowledge of the

Earth-sun system in some way protects against seasonal mood swings, perhaps by providing an explanation for winter’s relatively dark and cold environment as well as assurance that it will soon be replaced by spring.

Knowledge about SAD, unlike astronomical knowledge, correlated positively with GSS. Possibly, greater knowledge of SAD assists people in the

identification and classification of symptoms, which increases the likelihood

of report. Alternatively, learning more about SAD may actually cause people

to be more likely to experience and report the symptoms, or experiencing

strong seasonality may lead people to seek out more information about SAD.

Our data are consistent with Murray et al.’s (1995) report of a link between

neuroticism and the tendency to worse emotional functioning in winter. The

question of causality remains open, and two possibilities suggest themselves

to us. Firstly, it may be that high scorers on neuroticism have a tendency

toward more self-report of winter mood swings, possibly as part of a tendency to report more of both ailments. Secondly, and not mutually exclusively, Gordon et al. (1999) point out that there is a genetic locus that has been

implicated in both SAD and neuroticism, which opens the possibility that the

two measures are linked by a common cause. This will be an interesting topic

for future research. In this context, it is interesting to note that staff who are

selected to winter over on polar research stations are significantly lower on

neuroticism than are control participants (Steel, Suedfeld, Peri, & Palinkas,

1997).

Furthermore, in our data, GSS also correlated positively with extraversion. This builds up a picture of high GSS scorers as emotionally labile

extroverts who know less than average about the physical causes of the

annual cycle on Earth but more than average about the condition of SAD.

There were some interesting patterns in perceived swings in psychological functioning in oneself compared to those perceived in others and those

assumed in Arctic dwellers. The mediation analysis suggested that people

base their predictions of how the behavior of others at the same latitude varies

over the annual cycle on the ratings of their own swings and in turn base the

predictions about life in the Arctic on their predictions of others.

On the cognitive attributes, there was very little difference between the

seasonal swings participants reported for themselves and those they predicted for others, even those living in the Arctic Circle. This is consistent with

Downloaded from http://eab.sagepub.com at OSLO UNIV on February 13, 2007

© 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

234 ENVIRONMENT AND BEHAVIOR / March 2005

the available evidence from cognitive psychology that suggests there is little

seasonal variation in cognitive performance.

For the SAD-related attributes, few thought mood would be better in winter, and the most frequent response was that there would be no general seasonal change in mood, consistent with the growing consensus in the scientific

literature that season does not have a big effect on mood. On the other hand,

inconsistent with the literature on seasonal eating patterns in the Arctic,

although almost half the participants thought there was an increase in appetite in winter for themselves and others in London, only 7% thought there was

a similar increase for Arctic dwellers. Another misunderstanding of the

effect of the Arctic environment on humans was found in the questions on

sleep. During the polar winter, there is evidence that sleep patterns become

disturbed: People sleep longer, and the sleep is of lower perceived quality.

However more participants predicted this pattern for Londoners than for

Arctic people.

Generally, however, our sample did not have unduly pessimistic ideas

about mental life north of the Arctic Circle, which from the Arctic perspective is an uplifting conclusion. Consistent with the scientific evidence, the

modal response was for no seasonal variation in cognition or mood. Indeed,

just under half the sample said that there would not even be mood swings over

the annual cycle for people living in the Arctic. Other behaviors were

assumed to have similar sorts of swings in the Arctic as at London’s latitude.

Conversely, the sample as a whole failed to predict the well-established disturbances of sleep and eating during the Arctic winter.

The study also strengthened the link between personality and seasonality:

Highly seasonal people were low on emotional stability and high on extraversion. Furthermore, seasonality correlated negatively with astronomical

knowledge and positively with SAD knowledge.

REFERENCES

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173-1182.

Booker, J. M., & Hellekson, C. J. (1992). Prevalence of Seasonal Affective Disorder in Alaska.

American Journal of Psychiatry, 149, 1176-1182.

Brennen, T. (2001). Seasonal cognitive rhythms within the Arctic Circle: An individual differences approach. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21, 191-199.

Downloaded from http://eab.sagepub.com at OSLO UNIV on February 13, 2007

© 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Brennen et al. / SEASONAL PSYCHOLOGICAL FLUCTUATIONS 235

Brennen, T., Martinussen, M., Hansen, B. O., & Hjemdal, O. (1999). Arctic cognition: A study of

cognitive performance in summer and winter at 69°N. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 13,

561-580.

Diakidoy, I.-A., Vosniadou, S., & Hawks, J. D. (1997). Conceptual change in astronomy: Models

of the earth and of the day/night cycle in American-Indian children. European Journal of

Psychology of Education, 12, 159-184.

Eagles, J. M., Mercer, G., Boshier, A. J., & Jamieson, F. (1996). Seasonal affective disorder

among psychiatric nurses in Aberdeen. Journal of Affective Disorders, 37, 129-135.

Eagles, J. M., Wileman, S. M., Cameron, I. M., Howie, F. L., Lawton, K., Gray, D. A., et al.

(1999). Seasonal affective disorder among primary care attenders and a community sample

in Aberdeen. British Journal of Psychiatry, 175, 472-475.

Goldberg, L. R. (1990). An alternative “description of personality”: The Big-Five factor structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 1216-1229.

Gordon, T., Keel, J., Hardin, T. A., & Rosenthal, N. E. (1999). Seasonal mood change and

neuroticism: The same construct? Comprehensive Psychiatry, 40, 415-417.

Han, L., Wang, K., Cheng, Y., Du, Z., Rosenthal, N. E., & Primeau, F. (2000). Summer and winter

patterns of seasonality in Chinese college students: A replication. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 41, 57-62.

Hansen, V., Jacobsen, B. K., & Husby, R. (1991). Mental distress during winter. An epidemiologic study of 7759 adults north of the Arctic Circle. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 84,

137-141.

Hendriks, A. A. J., Hofstee, W. K. B., & de Raad, B. (1999). The Five-Factor Personality Inventory (FFPI). Personality and Individual Differences, 27, 307-325.

Hodges, S., & Marks, M. (1998). Cognitive characteristics of Seasonal Affective Disorder: A

preliminary investigation. Journal of Affective Disorders, 50, 59-64.

Husby, R., & Lingjærde, O. (1990). Prevalence of reported sleeplessness in northern Norway in

relation to sex, age and season. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 81, 542-547.

Kaler, J. B. (1994). Astronomy! New York: HarperCollins.

Kane, A., & Lowis, M. J. (1999). Seasonal Affective Disorder and personality, age, and gender.

South African Journal of Psychology, 29, 124-127.

Kasper, S., Rogers, S. L. B., Yancey, A., Schulz, P. M., Skwerer, R., & Rosenthal, N. E. (1989).

Phototherapy in individuals with and without Subsyndromal Seasonal Affective Disorder.

Archives of General Psychiatry, 46, 837-844.

Kasper, S., Wehr., T. A., Bartko, J. J., Gaist, P. A., & Rosenthal, N.E. (1989). Epidemiological

findings of seasonal changes in mood and behaviour. Archives of General Psychiatry, 46,

823-833.

Lee, T. M. C., & Chan, C. C. H. (1998). Vulnerability by sex to seasonal affective disorder. Perceptual & Motor Skills, 87, 1120-1122.

Magnusson, A., & Stefansson, M. D. (1993). Prevalence of Seasonal Affective Disorder in Iceland. Archives of General Psychiatry, 50, 941-946.

Mersch, P. P. A. (2001). Prevalence from population surveys. In T. Partonen & A. Magnusson

(Eds.), Seasonal Affective Disorder: Practice and research (pp. 121-141). New York: Oxford

University Press.

Mersch, P. P. A., Middendorp, H. M., Bouhuys, A. L., Beersma, D. G., & van den Hoofdakker, R.

H. (1999a). The prevalence of seasonal affective disorder in the Netherlands: A prospective

and retrospective study of seasonal mood variation in the general population. Biological Psychiatry, 45, 1013-1022.

Downloaded from http://eab.sagepub.com at OSLO UNIV on February 13, 2007

© 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

236 ENVIRONMENT AND BEHAVIOR / March 2005

Mersch, P. P. A., Middendorp, H. M., Bouhuys, A. L., Beersma, D. G., & van den Hoofdakker, R.

H. (1999b). Seasonal affective disorder and latitude: A review of the literature. Journal of

Affective Disorders, 53, 35-48.

Murray, G. W., Hay, D. A., & Armstrong, S. M. (1995). Personality factors in seasonal affective

disorder: Is seasonality an aspect of neuroticism? Personality and Individual Differences, 19,

613-617.

Nilssen, O., Lipton, R., Brenn, T., Høyer, G., Boiko, E., & Tkatchev, A. (1997). Sleeping problems at 78 degrees north: The Svalbard study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 95, 44-48.

Palinkas, L. A., & Houseal, M. (2000). Stages of change in mood and behavior during a winter in

Antarctica. Environment and Behavior, 32, 128-141.

Palinkas, L. A., Houseal, M., & Rosenthal, N. E. (1996). Subsyndromal Seasonal Affective Disorder in Antarctica. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 184, 530-534.

Perry, J. A., Silvera, D. H., Rosenvinge, J. H., Neilands, T., & Holte, A. (2001). Seasonal eating

patterns in Norway: A non-clinical population study. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology,

42, 307-312.

Roald, I., & Mikalsen, Ø. (2001). Configuration and dynamics of the Earth-Sun-Moon system:

An investigation into conceptions of deaf and hearing pupils. International Journal of Science Education, 23, 423-440.

Rosen, L. N., Targum, S. D., Terman, M., Bryant, M. J., Hoffman, H., Kasper, S. F., et al. (1990).

Prevalence of Seasonal Affective Disorder at four latitudes. Psychiatry Research, 31, 131144.

Rosenthal, N. E. (1998). Winter blues (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford.

Rosenthal, N. E., Sack, D. A., Gillin, J. C., Lewy, A. J., Goodwin, F., Davenport, Y., et al. (1984).

Seasonal affective disorder, a description of the syndrome and preliminary findings with

light therapy. Archives of General Psychiatry, 41, 72-80.

Schlager, D. S. (2001). Melatonin. In T. Partonen & A. Magnusson (Eds.), Seasonal Affective

Disorder: Practice and research (pp. 175-186). New York: Oxford University Press.

Steel, G. D., Suedfeld, P., Peri, A., & Palinkas, L. A. (1997). People in high latitudes: The “Big

Five” personality characteristics of the circumpolar sojourner. Environment and Behavior,

29, 324-347.

Suedfeld, P., & Weiss, K. (2000). Antarctica: Natural laboratory and space analogue for psychological research. Environment and Behavior, 32, 7-17.

Taylor, A. J., & Duncum, K. (1987). Some cognitive effects of wintering-over in the Antarctic.

New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 16, 93-94.

Thompson, C., & Isaacs, G. (1988). Seasonal Affective Disorder—A British sample. Journal of

Affective Disorders, 14, 1-11.

Vosniadou, S., & Brewer, W. F. (1992). Mental models of the Earth: A study of conceptual

change in childhood. Cognitive Psychology, 24, 535-585.

Vosniadou, S., & Brewer, W. F. (1994). Mental models of the day/night cycle. Cognitive Science,

18, 123-183.

Downloaded from http://eab.sagepub.com at OSLO UNIV on February 13, 2007

© 2005 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.