Susan K. Murray-Ritchie for the degree of Doctor of Education... on April 29. 1998. Title: Autistic Conflict in Higher Education.

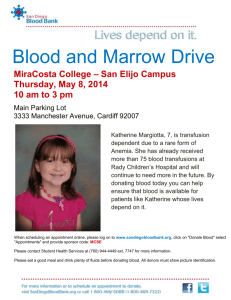

advertisement