Document 11404818

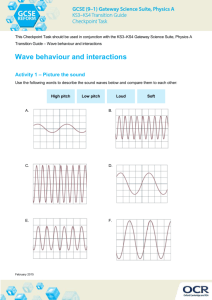

advertisement