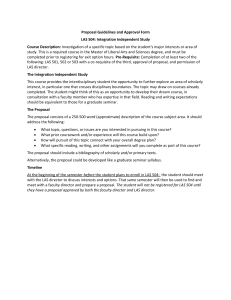

Human Development

advertisement