Jaroslaw Kwapisz Center for Dynamical Systems and Nonlinear Studies Atlanta, GA 30332-0190

advertisement

On quotient-convergence factors.

Jaroslaw Kwapisz

Center for Dynamical Systems and Nonlinear Studies

Georgia Institute of Technology

Atlanta, GA 30332-0190

May, 1994

1

Introduction and statement of results.

Consider the following recurrence

(

x = x + x ; n = 0; 1; 2; :::

x = x;

n+1

n

(1)

n

0

where x 's belong to a certain linear space X over the eld of real numbers

R, is a linear operator on X and 2 R is xed. If is assumed to be

small (in the sense yet to be made precise), then one may think of (1) as

a perturbation of the problem y = y , y = x. It is expected then

that the behavior of the perturbed sequence (x ) resembles that of (y ). Our

main result, stated below and proved in Section 1, is a new instance of this

familiar situation.

n

n+1

0

n

n

n

Theorem 1 Suppose that (x ) satises (1) and that

n

: X ! R is an

arbitrary linear functional. If either

(U) lim !1 lim sup !1 j (

+1 x )= (

x )j = 0,

or

(P) lim !1 (

+1 x0 )= (

x0 ) = 0 and > 0, (

x0 ) > 0, k = 0; 1; 2:::,

then

lim

!1 (x +1 )= (x ) = :

k

k

k

n

k

n

k

n

1

k

n

k

n

n

Revised in September 1996.

1

The usefulness of Theorem 1 may be seen in the context of the waveform

relaxation (WR) method as considered in [1]. While the reader should consult

[1] for the details, let us recall that it deals with an initial value problem for

a functional-dierential system of the form y0(t) = f (t; y(); y0()), where

t 2 [a; b] and y(t) 2 R . The functional f takes as arguments functions

dened over [; b] for some a (thus allowing for delays) and is assumed

to satisfy the following Lipshitz condition with L 0, 1 > K 0 and k k

standing for the sup norm over [a; t]:

d

t

kf (t; y(); z()) f (t; y~(); z~())k Lky y~k + K kz z~k ;

for any continuous functions y; y~; z; z~ and t 2 [a; b].

t

t

(2)

The idea of the WR method is in decoupling the system by exploiting an

initial approximation to the solution | which allows for parallel numerical

integration of the dierent components | and then bootstrapping this procedure to construct an iterative scheme that renders consecutive approximations to the true solution. For example, by totally decoupling the components

of y the WR Gauss-Jacobi iteration is obtained:

z (t) = f (t; y (); :::; y (); y (); y (); :::; y ();

z (); :::; z (); z (); z (); :::; z ());

i = 1; :::; d, where z (t) = y (t), t 2 [a; b] and n = 0; 1; 2; ::: .

From (2), the error v (t) := kz

zk := sup kz (s) z(s)k

satises a bound v (t) u (t) exp (A(t a)) where u is dened via

(n)

i

i

(n

1

(n

1

1)

(n

1)

1)

1

i

(n

(n)

1)

1

i

(n

i+1

(n)

(n

i

i+1

1)

(n

(n)

1)

(n

(n)

(n)

t

a

s

u (t) = Ku

1)

t

(n)

iteration (see (2.4) in [1])

(n

1)

d

(n)

(n)

1)

d

(n)

d

dt

(n)

(n)

i

(t) + M

Z

t

a

u

(n

1)

(s)ds; n 2 N;

(3)

with the initial value u (t) = v (t) exp ( A(t a)) and A; M > 0 some

constants. In further reduction, the sequence

X n ! (M (t a)) K

;

(4)

(t) =

i

i!

(0)

(0)

n

i

(n)

n

i

i=0

which is exactly the solution of (3) for the initial data equal to 1, is used for

the majorization u (t) Z (t), Z := sup v (t); and the linear

convergence of the WR method derives from the following theorem.

(n)

0

(n)

0

2

(0)

a

t

b

Theorem 2 (Th. 2 in [1]) If (t) is dened by (4), then, for any t 2

(n)

[a; b],

lim

!1 (n+1)

n

(t)= (t) = K:

(n)

The key iteration (3) is clearly an instance of (1) with = K and =

,

Z

x(t) = x(s)ds; t a;

(Vol)

t

(Vol)

a

and = x under the initial condition x (t) = 1, t 2 [a; b]. By taking for

the functional of evaluation at a xed instant t, Theorem 1 yields Theorem

2 provided we can verify, say, hypothesis (P). For this we calculate:

(n)

0

n

k + 1)! = (t a)=(k + 1) ! 0:

(1)(t)=

(1)(t) = (t (at ) a)=(=k

!

In this way Theorem 2 is a manifestation of a more general phenomenon

regarding quotient-convergence factors | as the limits involved are often

referred to, see Denition 9.1.1 in [3]. One advantage of this approach may

be that it applies to the iteration (3) with less stringent initial conditions

deprived of an explicit formula like (4). Indeed, the following fact, proved in

Section 2, veries the hypothesis of Theorem 1 (in the WR context) under

more general circumstances.

k +1

k +1

k

k

Fact 1 If x (t) is dened by (1) with = and > 0, then

n

o

j

x

(

t

)

=

x

(

t

)

j

= 0;

lim

sup

!1

(Vol)

n

k

n

k +1

2N

k

n

n

under either of the two following assumptions on the initial condition

(i) x0 (t) is non-decreasing and positive for t 2 (a; b);

(ii) x0 (0) 6= 0 and x0 (t) is continuous for t 2 [a; b).

Finally, let us note here that it is standard and much easier to show

a weaker form of Theorem 2 concerning the root-convergence factors (see

Denition 9.2.1 in [3]). Namely, for x = and = K , we have

qn

lim

!1 x (t) = :

n

n

n

3

(n)

The limit on the left-hand side is, in fact, equal to the spectral radius (T )

of T := Id+

with respect to the sup-norm over the interval [a; t].

(This follows for example from Theorem 9.1 in [2].) Thus, we recognize the

above equality as an instance of the following well known theorem: if is

a scalar and is a linear operator with (

) = 0, then ( Id + ) = .

One may think of Theorem 1 as an analog of the above result. Actually,

for the spectral radius a more general statement holds : if and are two

commuting linear operators and (

) = 0, then (+

) = (). This is an

immediate consequence of sub-additivity of the spectral radius on commuting

operators (see e.g. chapt. 2, equ. 5.2 in [2]).

Nevertheless, the analogous statement for the quotient-convergence factors is most likely not true. More specically, there should be a linear space

X , two commuting linear operators and , a linear functional and

x 2 X , such that, for x := ( + ) x, the quotients (

x )= (

x )

and ( x )= ( x ) converge uniformly in n to and 0 respectively, but

(x )= (x )'s does not converge to . The author does not know any such

examples.

(Vol)

(Vol)

(Vol)

k +1

n+1

n

k

k +1

n

n

k

n

n

n

n

Section 1: Proof of Theorem 1.

Let us rst argue that hypothesis (P) implies hypothesis (U). By the

binomial formula, we have

X n!

(5)

x = ( + ) x =

j x:

n

n

n

n

0

j

j

0

j =0

Inserting this formula into (

(x ))= (

(x )) we get a quotient of two

sums. Since all the terms are positive, we can dominate it by the maximum

of quotients of corresponding terms i.e. max f (

x )= (

x )g.

Now, hypothesis (P) implies that these maxima converge to 0 as k tends to

innity | (U) follows.

In what follows we will prove the assertion of Theorem 1 under hypothesis

(U). Note that we may assume that = 1. Indeed, otherwise one can force

this condition by substitution x~ := x . Set

k +1

k

n

n

n

j =0

n

n

n

x := x ; k; n = 0; 1; 2; ::: :

k

n;k

n

4

j +k +1

0

j +k

0

From (1) we have

x

n+1;k

=x +x

n;k +1

n;k

; k; n = 0; 1; 2; ::: :

(6)

So, to investigate the quotients (x )= (x ) we may represent them as

1 + , where

:= (x )= (x ):

We have to prove that converges to zero as n ! 1.

Using (6) one can see that 's satisfy the following recurrence equation

(7)

= 11++ :

This kind of recurrence relation guarantees strong ties between the limit

behavior of the two sequences involved. The following lemma, which we

prove later, is critical for our argument.

n+1;k

n;k

n;k

n;k +1

n;k

n;k

n;0

n;k

n;k +1

n+1;k

n;k

n;k

Lemma 1 If a > 1, n = 1; 2; 3; ::: and reals z satisfy

n

n

a;

= z 11 +

(8)

+z

then minf0; lim inf a g lim inf z lim sup z maxf0; lim sup a g:

z

n

n+1

n

n

n

n

n

n

Denote lim sup !1 and lim inf !1 by and respectively.

Assumption (U) of Theorem 1 guarantees that lim !1 = lim !1 = 0.

In particular, for suciently large k, > 1, and we can use Lemma 1

with a := and z := to conclude that

n;k

n

n

+

n;k

k

k

k

+

k

k

k

k +1

n

n;k +1

n

n;k

minf ; 0g minf ; 0g maxf ; 0g maxf ; 0g:

+

k +1

k

+

k +1

k

Note that necessarily > 1, so we can get analogous inequalities with k

replaced by k 1 by invoking Lemma 1 again with a := , z := .

Repeating this k times leads to

k

n

n;k

n

n;k

1

minf ; 0g minf ; 0g maxf ; 0g maxf ; 0g:

k

+

0

0

+

k

In the limit k ! 1, we get = lim !1 = 0 and = lim !1 = 0.

This ends the proof of Theorem 1. 2

+

0

k

5

+

k

0

k

k

Proof of Lemma 1. First let us make a technical observation that, due

to a > 1, we have z > 1 for large enough n. Indeed, if for some n we

have z 0 < 1, then z 0 = z 0 nn00 1 + a 0 > 0. On the other hand,

again from (8), we see that once z > 0, then z > 0 for k = 1; 2; 3; ::: .

If z converged, then, by passing to the limit in (8), we would see that so

does a and lim a = lim z | we would be done.

Denote by I the interval with the endpoints a ; 0 and let I be an arbitrary

interval such that min I < lim inf min I lim sup max I < max I . Clearly

I I for large n. We would be done if we could see that almost all z sit

in I . Let us assume for now the following claim.

n

n

n

n

0

1+a

+1

n

n

1+z

n+k

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

Claim 1 The following alternative holds for z > 1 :

(*) if z 62 I , then z z ;

(**) if z 2 I , then z z max I .

n

n

n

n

n

n+1

n

n

n+1

n+1

∞

∞

a<0

a>0

a

a

0

0

Action of iterates of f on the points of the circle of reals.

a

Observe that, if for some large n , z 0 2 I , then either z 0 < min I or

z 0 2 I . Indeed, otherwise z 0 min I and z 0 62 I , which means that

z 0 > max I . This however is incompatabile with neither (*) nor (**) of

Claim 1. Moreover, once z < min I then by (*) we have z z min I ,

so, by induction, z < min I for almost all z 's.

0

n

+1

n

+1

n

n

n

+1

n

n+1

n

n

n

6

+1

+1

n

In this way, if z hits I and subsequently leaves it, then z never comes

back to I again. Thus, either almost all z sit in I and we are done, or almost

all z lie outside I . In the later case, by (*), we see that z is non-increasing,

so it is convergent | and we are done as well. 2

Proof of Claim 1. According to (8) we have z = f n (z ), where f (z) :=

(1 + a)z=(1 + z). For a > 1, this map has two xed points z = 0 and z = a.

If I is the interval with endpoints at these xed points and z > 1, then

f (z) z for z 2 I , and f (z) z for z 62 I . Simple verication is left for

the reader. 2

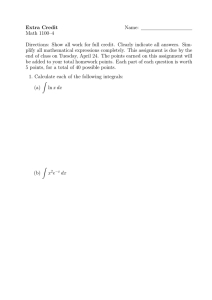

The proof of Lemma 1 is technical. One can gain an intuitive picture of

what is going on by thinking of z as lying on the circle of real numbers with

1 that is acted upon by the Mobius transformations f (z) := (1 + a)z=(1 +

z); a = a > 1. Each of these transformations has dynamics depicted

in the gure. Of course the fact that a 's are not constant adds diculty

to understanding how points z move along the circle, but one thing which

should be fairly clear (at least for small a 's) is the following: as n increases,

z either goes once around the circle and then must stay near maxf0; a g, or

it persists near minf0; a g. This is, very roughly, the idea of Lemma 1.

Let us indicate here that, if one is interested only in the case where a 's

and z 's are positive (as encountered in hypothesis (ii) or [1]), then Lemma

1 has the following stronger analogue with a more esthetic proof.

Lemma 2 (positive case) If a > 0; n = 1; 2; 3; ::: and z > 0 satisfy

(9)

z = z 11 ++ az ;

then lim inf a lim inf z lim sup z lim sup a :

n

n

n

n

n

n+1

a

a

n

a

a

n

a

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n+1

n

n

n

n

n

n

Proof of Lemma 2. Choose a ; a arbitrarily so that lim sup a <

a ; lim inf a > a . If the sequence (z ) had a limit, (9) would yield

lim z 1 1++limliminfz a lim z lim z 1 +1 +limlimsupz a ;

+

n

+

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

and we would be done by comparison of the numerators and denominators

above. Dividing term by term in (9), we get

minfa ; z g z maxfa ; z g:

n

n

n+1

7

n

n

Let us deal with lim sup-part of our lemma | for the lim inf-part the

analogous argument works. If z a for some large n, then z maxfa ; z g a . Repeating this argument, we see that z a ,

k = 1; 2; 3; :::, so lim sup z a , as required. If z a for all large n, then

in particular z a and, by the right inequality, we see that z z .

Thus z is eventually non-increasing, so it has a limit | we are done. 2

+

n

n

n+1

+

n

n+k

+

n

n

+

+

n

n+1

n

n

n

Section 2: Proof of Fact 1.

Since there is no danger of ambiguity, we will abbreviate to . Also,

setting a = 0 and b = 1 will simplify the notation without compromising

generality. Let us rst deal with (i). It is easy to see that all of x (t) are

positive and non-decreasing in t. Hence, we will be done by showing the

following fact.

(Vol)

n

Fact 2 If x(t) is positive and non-decreasing for t 0, then

(

x)(t)=(

x)(t) kt :

k

k

1

Proof of Fact 2. Dene operators A by

Z

(A x)(t) := k=t x(s)s ds; t 0; k = 1; 2; 3; ::: :

k

t

k

k

k

1

0

Note that the right hand side above is an average. Thus we have

sup j(A x)(s)j sup jx(s)j:

s

k

t

s

(10)

t

In particular, A sends non-decreasing functions to non-decreasing ones.

Also, a straight-forward verication conrms that

k

= kt ! A A

In this way, we can write

k

k

k

(

x)(t)=(

x)(t) = t (A A

k

k

1

k

k

k

1

8

k

1

::: A :

(11)

1

::: A x)(t)=(A

1

k

1

::: A x)(t):

1

Inequality (10) yields (A A ::: A x)(t) (A ::: A x)(t), and we

conclude that

(

x)(t)=(

x)(t) t : 2

k

k

1

1

k

k

1

k

1

1

k

We will deal with (ii) now. With no loss of generality we can assume that

x (0) > 0. It is a routine to see that

0

Z

Z

(

x)(t) = (k 1 1)! x(s)(t s) ds = kt ! tk x(s)(t s) ds:

t

k

k

k

1

t

k

0

k

1

0

For xed t, the kernels k (t s) , s 2 [0; t], approximate the delta-mass

distribution concentrated at 0, so

!

t

lim

(

x )(t)= k! x (0) = 1:

(12)

!1

k

k

t

k

k

k

0

0

Hence, we have

!

!

t

t x (0) = 0:

lim

(

x

)(

t

)/(

x

)(

t

)

=

lim

x

(0)

=

!1

!1 (k + 1)!

k!

k +1

k

k +1

k

0

0

0

k

Now, using binomial formula (5), we can write

P

n

(

x )(t)=(

x )(t) =

k +1

k

n

k

n

j =0

P

n

j =0

n

(13)

!

n (

x )(t)

j !

:

n (

x )(t)

j

j +k +1

j

n

0

j

j +k

0

0

Note that, due to (12), for large enough k, all terms in the numerator and

the denominator are positive. This makes it possible to divide term by term

to get the following estimates

(

)

)

(

(

x

)(

t

)

(

x

)(

t

)

min (

x )(t) (

x )(t)=(

x )(t) max (

x )(t) :

n

j +k +1

j =0

j +k

0

k +1

n

k

n

n

0

j =0

j +k +1

j +k

0

0

It follows by (13) that (

x )(t)=(

x )(t) converges to 0 uniformly in

n, as k ! 1. 2

k +1

k

n

9

n

References

[1] Z. Jackiewicz, M. Kwapisz, and E. Lo, Waveform relaxation methods for

functional dierential systems of neutral type, J. Math. Anal. Appl. 207

(1997), 255{285.

[2] M. A. Krasnosel'skii, G. M. Vainikko, P. P. Zabreiko, Ya. B Rutitskii, and

V. Ya. Stetsenko, Approximate solution of operator equations, WoltersNoordho Publishing, Groningen, 1972.

[3] J. M. Ortega and W. C. Rheinboldt, Iterative solutions of nonlinear equations in several variables, Academic Press, New York and London, 1970.

10