Document 11386065

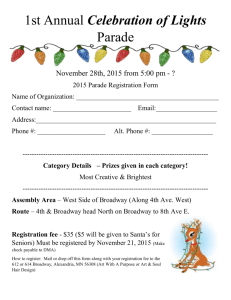

advertisement