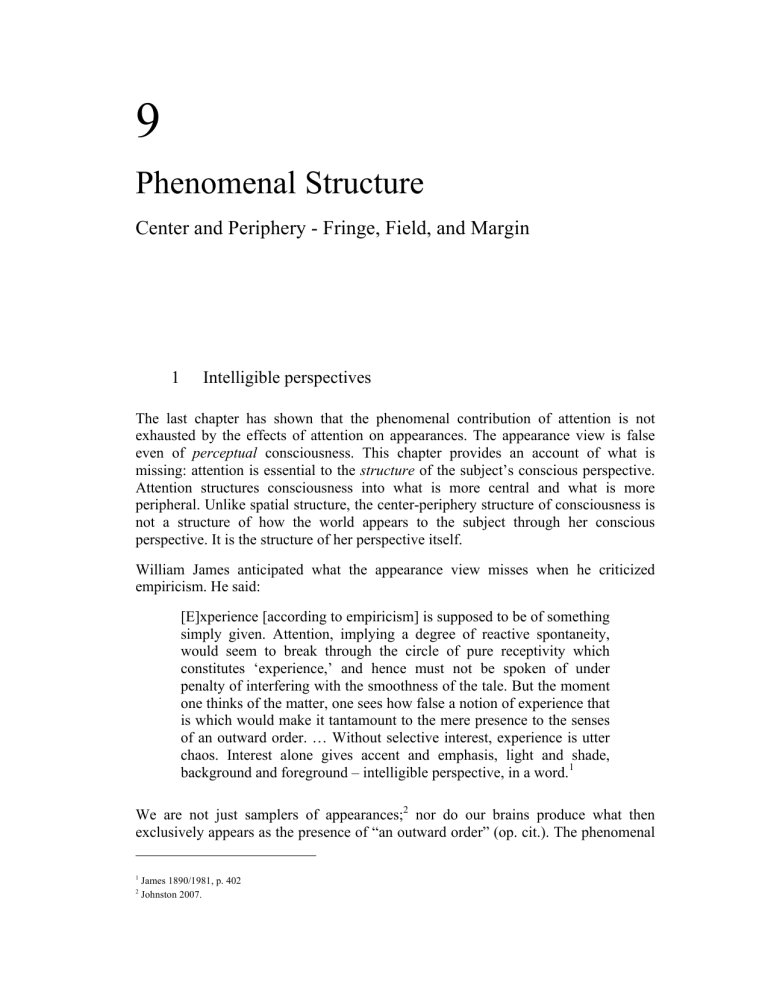

9 Phenomenal Structure Center and Periphery - Fringe, Field, and Margin

9

Phenomenal Structure

Center and Periphery - Fringe, Field, and Margin

1 Intelligible perspectives

The last chapter has shown that the phenomenal contribution of attention is not exhausted by the effects of attention on appearances. The appearance view is false even of perceptual consciousness. This chapter provides an account of what is missing: attention is essential to the structure of the subject’s conscious perspective.

Attention structures consciousness into what is more central and what is more peripheral. Unlike spatial structure, the center-periphery structure of consciousness is not a structure of how the world appears to the subject through her conscious perspective. It is the structure of her perspective itself.

William James anticipated what the appearance view misses when he criticized empiricism. He said:

[E]xperience [according to empiricism] is supposed to be of something simply given. Attention, implying a degree of reactive spontaneity, would seem to break through the circle of pure receptivity which constitutes ‘experience,’ and hence must not be spoken of under penalty of interfering with the smoothness of the tale. But the moment one thinks of the matter, one sees how false a notion of experience that is which would make it tantamount to the mere presence to the senses of an outward order. … Without selective interest, experience is utter chaos. Interest alone gives accent and emphasis, light and shade, background and foreground – intelligible perspective, in a word.

1

We are not just samplers of appearances; 2 nor do our brains produce what then exclusively appears as the presence of “an outward order” (op. cit.). The phenomenal

1 James 1890/1981, p. 402

2 Johnston 2007.

192 Phenomenal Structure character of conscious experience includes the actively structured point of view on the appearances. Our experience is organized and thus an “intelligible perspective”

(op. cit.). What it is like for us includes the way we are structuring consciousness into

“foreground and background” (op. cit.).

Of course, appearances need not be chaotic. The (apparent) world we encounter in phenomenal consciousness is organized spatially, temporally, and into distinct perceptual objects and properties. What would be “utter chaos” (op. cit.) is the subject’s experience (not what is present in that experience). Attention provides the structure of the subject’s subjective experiential perspective.

While the appearance view thus provides an account of phenomenal qualities , it overlooks that these qualities occur in a phenomenal structure that gives shape to the perceptual experiences that are the focus of the appearance view. The appearance view only accounts for the qualitative character of consciousness. By missing phenomenal structure it misses that conscious experience presents the world of appearances from a structured point of view . Because we look through our point of view to the world this element of “spontaneity” (op. cit.) is easy to miss. The centerperiphery structure of consciousness is never the object of conscious attention. It is our conscious attention.

The phenomenal character of conscious attention thus reflects the nature of attention: the relative priority of some psychological parts over others. Priority structures (the constitutive resultant states of attending) are reflected in conscious experience as phenomenal structure (we will get to the phenomenal reflection of the guidance of attention in the two chapters that follow the present one). Without attention, experience would be an unordered bundle of appearances while with attention it is structured. The parts of your experience are ordered from those that are most central to those that are peripheral. The proposal thus is the following.

3

Phenomenal Structuralism Complex experiences are structured by attention so that some of their parts are more central than others.

Phenomenal structuralism can account for the natural idea that attention has a single phenomenal core, i.e. what I have called the phenomenal uniqueness of attention (p.

170 ff). The type of phenomenal character that is common to all forms of attention is phenomenal structure, and not a type of appearance. The phenomenal structure of experience, of course, is not always the same. It may be simple or complex. There may be one central element or many, and the structure can take various forms including the shape of a complex “attentional landscape”.

4 The structure of experience is present whether attention is highly focused or divided or distributed.

The fact that your experience is centrality structured is what constitutes the phenomenal property shared by all conscious attention episodes.

3 I briefly discuss precursors of a view like this in the Appendix to this chapter (p. 219 ff).

4 Datta and DeYoe 2008

Structured building 193

2 Structured building

How then should we think of the relevant structure?

Consider your experience when looking at two letters: L on the left, and R on the right. Your experience is a complex phenomenal state E with at least two states as parts. First, there is a part that is intentionally directed at L (your experience of L ) : e

L

.

And second, there is a part that is intentionally directed at R (your experience of R): e

R

. Considered by themselves the phenomenal properties of each of these parts may be exhausted by their appearance properties. Let us call the parts of a complex experience that have such appearance properties the qualitative parts of that complex experience.

The subject’s complex experience E, then, is built from qualitative parts like e

L e

R

.

and

According to phenomenal structuralism the appearance view remained incomplete because of its overly simplistic account of that building relation, i.e. on the appearance view there is no structure to the way complex experiences are built from their parts.

The appearance view might, for example, see E as the mereological sum of phenomenally unified simple experiences. We would get something like the following (where ‘a + b’ depicts the mereological sum of phenomenally unified experiences a and b).

5

Mereological Building E = e

L

+ e

R

A certain version of the intentionalist interpretation of the appearance view could dispense with the mereological characterization in favor of a characterization of a single phenomenal state with a conjunctive content as follows (where c

L and c

R now are the contents represented by e

L

and e

R respectively and ‘x & y’ is a conjunctive operation on contents x and y).

6

Conjunctive Building E = experiencing c

L

& c

R

None of this captures the center-periphery structure of experience. In contrast to these proposals we need structured building. The way a complex experience is made up from simpler experiences is organized. The complex phenomenal state should be represented by an ordered pair where the relevant ordering is provided by a relation of relative centrality. Complex experiences are more than the sum of their parts. They are structured wholes; more like molecules than like heaps of pebbles. We can represent this as follows.

5 Bayne and Chalmers 2003 or Bayne 2010a.

6 See Tye 2003. If x and y are propositions then ‘&’ is propositional conjunction. If x and y are non-propositional (e.g. like

Burge’s (2010) complex demonstratives), then ‘&’ might function somewhat differently (we will have ‘This-F & This-G’).

194 Phenomenal Structure

Structural Building E = e

L

≻ e

R

7

Here x

1

≻ x

2

holds just if x

1

is more central in experience than x

2

. According to phenomenal structuralism the parts of experience thus bear phenomenally significant relations to each other. The ordering of the complex experiential episode would be lost when considering only mereological or conjunctive building. What the counterpart argument of the last chapter shows is that the ordering is phenomenally significant.

Phenomenal structuralism is compatible with much of the spirit of the appearance view. In particular, it is compatible with the claim that the phenomenal properties of each qualitative part of a complex experience consist in a certain way the world appears to the subject (i.e. appearance properties). When we consider a simple phenomenal state such as the experience of a color chip the appearance view might be the correct account of that episode considered, as it were, in isolation. Let us say that the appearance view is correct when restricted to phenomenal qualities .

What the appearance view misses is that besides phenomenal qualities there is also phenomenal structure that relates the parts of a complex phenomenal state. In particular, some of these parts are more central than others. This is what structuralism adds to the appearance view. A complex phenomenal state has an overall phenomenal quality (this is what the appearance view gives an account of), and it has an internal structure (this is what phenomenal structuralism accounts for). This structure, at least to first approximation, is given by the set of centrality relations ‘ ≻ ’ that hold between the various parts of the conscious experience (more in just a moment). We can call it the centrality structure of experience. The complete phenomenal property of a complex experience is thus constituted by (a) the phenomenal qualities of each of its qualitative parts, and (b) the phenomenal structure that relates these qualitative parts.

3 Priority and centrality

Why should we account for what the appearance view misses in terms of phenomenal structure? Why not account for it in some other way?

The answer is that the centrality ordering within a subject’s complex experience is a direct phenomenal reflection of the priority ordering that is constitutive of attention.

The reason we could find a counterpart for each effect of attention on the appearances was that all of these are mere effects or correlates of a certain distribution of attention. It was thus possible to replicate the relevant effects in a scenario with a different distribution of attention. Priority structures, by contrast, are not mere effects or correlates of attention. They are partially constitutive of attention. A phenomenal

7 This representation is somewhat misleading (since E is not the fact that e

L

is more central than e

R

.) E

L

is itself an event that is composed of two sub-events in such a way that one of them is more central than the other. A more precise representation might be E

L

= (e

L

, e

R

)

>

. Since the same problem of representation affects the mereological view, I chose the less precise but hopefully more intuitive representation.

Priority and centrality 195 contribution of a certain distribution of attention that is constituted by priority structures cannot be replicated with a different distribution of attention.

The simplest account of how centrality structure and priority structure hang together is identity. We would thus have the following.

Identity Mapping For x

1

≻ x

2

just is for x

1

> x

2 i.e. for one qualitative part to be more central in the subject’s experience than some other qualitative part just is for the qualitative part to be strictly prioritized over that other qualitative part.

According to the identity mapping view priority relations thus are phenomenal relations , i.e. relations whose obtaining makes a difference to what it is like for a subject. The holding of these phenomenal relations between the qualitative parts of a subject’s experience explains why what it is like to have an experience with one distribution of attention is different from what it is like to have an experience with a different distribution of attention.

The identity mapping view does not entail that attention is always conscious. As we will see in Chapter 12 there is empirical evidence that consciousness is not necessary for attention (and so attention is not sufficient for consciousness). The identity mapping view can account for this possibility. The holding of priority relations will make a phenomenal difference only if those relations relate qualitative part s, where a qualitative part, as I have said, is one that instantiates phenomenal qualities.

According to the identity mapping view priority relations are restricted phenomenal relations in the following sense.

Restricted Phenomenal Relation A binary relation x

1

Rx

2 is a restricted phenomenal relation just if, given that x

1

and x

2

instantiate phenomenal qualities, any world where x

1

Rx

2 holds is phenomenally different from a world where x

1

Rx

2 does not hold.

The relata that enter into the priority relation thus need to be suitable in order for the holding of the priority relation to make a phenomenal difference. If they are suitable then it necessarily makes a phenomenal difference. If they are unsuitable it does not make a phenomenal difference. Phenomenal structure depends on phenomenal qualities.

According to the view I will defend in Chapter 13, phenomenal qualities also depend on phenomenal structure. All phenomenal qualities are restricted phenomenal properties in the sense that there is something it is like to experience a phenomenal quality only if that quality is embedded in a centrality structure. On this view, then, there is symmetry between phenomenal qualities and phenomenal structure: neither contributes to what it is like for a subject without the other. Qualities and structure need to be put together to yield conscious experience. On the resulting view, conscious experience consists in the subject’s engaged perspective on an apparent world. Centrality structure is the form of that perspective. Phenomenal qualities are its matter .

196 Phenomenal Structure

But one does not have to accept this view in order to think that priority relations are restricted phenomenal relations. It is consistent to hold both that there is something it is like to experience a phenomenal quality even in the absence of any priority structure, and to hold that phenomenal structure makes a distinctive phenomenal contribution. Arguably, priority relations would then be like temporal or geometric relations: what it is like to experience first a headache and shortly thereafter experience nausea is different from what it is like to first experience the nausea and then experience the headache. The temporal relation between the headache and the nausea thus makes a phenomenal difference. But, of course, temporal relations make a phenomenal difference only if they are temporal relations between phenomenal experiences. The temporal relation between two unconscious mental states makes no phenomena difference.

According to the identity mapping view, the centrality structure of conscious experience can be straightforwardly identified with structure that is not always phenomenal structure.

The identity mapping view, of course, is not the only option. It is also possible to hold that the relationship between centrality structure and priority structure is less direct.

An extreme view might be called dualism about phenomenal attention.

On this view, relative centrality in conscious experience and relative priority are fully independent.

Dualism about phenomenal attention is one way to develop the idea that there is both a functional and a phenomenal notion of attention.

8 On this view, phenomenal attention is a structuring of experience in terms of centrality, and functional attention is a structuring of the mind in terms of priority. While phenomenal attention could be structurally isomorphic to functional attention, on this view there are no constraints, on how centrality and priority are related.

Dualism about phenomenal attention Whether x

1 whether x

1

> x

2

≻ x

2 is independent of

Dualism about phenomenal attention would allow for inversions between centrality and priority. On this view it would be (even) physically possible that x

1

≻ x

2

while x

1

< x

2

. That is, it would be physically possible that some qualitative part is prioritized over another, yet at the same time it is less central in the subject’s field of consciousness.

Dualism about phenomenal attention is a coherent position. But, in my view, it is not very attractive. Relative priority (and its correlates in attentional processing) and relative centrality in consciousness appear to go together at least in us. Unlike

(functionally indistinguishable) color inversion (where what looks phenomenally red to one creature will look phenomenally green to another functionally identical creature), centrality/priority inversion prima facie seems inconceivable. What would it be like to invert central and peripheral consciousness while keeping all functional

8 Smithies (2011) discusses this option. It has also been suggested by David Chalmers in personal communication (CHECK with him).

Phenomenal structure or modes of consciousness? 197 characteristics intact? Inversion with respect to relative centrality seems more like pleasure/pain inversion than like red/green inversion. While the latter seems prima facie conceivable the former seems prima facie inconceivable. While most of what I will say in what follows is consistent with dualism about phenomenal attention, I will thus assume that it is rejected (proponents of dualism about phenomenal attention will need to replace my talk of the nature of attention with “the nature of phenomenal attention).

There is a more subtle revision of the identity mapping view, though. This view rejects the possibility of centrality/priority inversions, but allows for the possibility of attention specific zombies . Consider a creature whose mind contains qualitative parts that are priority related to each other and yet those priority relations make no difference to what it is like for that creature. While in us the priority relations between the relevant qualitative parts contribute to our overall phenomenal experience, in this attention specific zombie they make no phenomenal contribution. The identity mapping view rules out the metaphysical possibility of such an attention specific zombie, since it identifies centrality with priority. Let us then consider a view that allows for the possibility of attention specific zombies, but rejects centrality/priority inversions. According to a weak mapping view, the connection between priority and centrality is one of natural law and not of metaphysical necessity. We thus get the following.

Weak mapping Given that x

1

and x

2

are qualitative parts:

(a) With metaphysical necessity: if x

1

≻ x

2, then x

1

> x

2

,

(b) With natural necessity: if x

1

> x

2

, then x

1

≻ x

2

The weak mapping view could still hold that priority structures are metaphysically necessary for conscious experience, but they won’t be metaphysically sufficient even if they embed phenomenal qualities. The decision between the weak mapping and the identity mapping view is likely independent of any attention specific arguments. It will depend on one’s general views about the strength of conceivability arguments. If

– in general – one finds it conceivable that a molecule for molecule duplicate of me lacks conscious experience, and if one finds persuasive that the relevant conceivability entails the possibility of such a zombie duplicate, then attentional zombies will be possible too. In this case, one should accept only weak mapping. By contrast, if one is not persuaded of dualism by general conceivability arguments then one should probably accept the identity of relative priority and relative centrality and thus the identity mapping view. Since it is not the goal of this book to engage with conceivability arguments, and since the choice between weak mapping and identity mapping won’t matter for my purposes, I will thus leave open whether weak mapping or identity mapping is the correct view.

4 Phenomenal structure or modes of consciousness?

How does phenomenal structuralism compare to alternatives?

198 Phenomenal Structure

One apparent alternative is to suggest that attention contributes a particular mode of consciousness (this may have been Husserl’s view, which we encountered at the end of the last chapter). Modes of consciousness here are different ways of being intentionally directed at some object, property or content. Consider, for example, impure intentionalism that holds that the phenomenal properties of an experiential episode supervene on the bearing of intentional attitudes (or modes) towards contents.

9 Arguably, the phenomenal differences between the sensory modalities such as vision and touch, or phenomenal differences between perception and conscious thought, are partially explained in terms of differences in the mode of consciousness.

10 Maybe, then, the phenomenal contribution of attention – insofar as it goes beyond appearances – is captured by an attention mode of consciousness?

If attention most fundamentally were an intentional attitude or mode, this view would have considerable attraction. The first half of this book has argued for a different view of the nature of attention: attention is not an intentional attitude. It is a structure of the mind. This considerably weakens the attractions of the mode view. This weakness can be put in terms of a dilemma. On the first horn consider a view on which the relevant mode of consciousness is independent of the nature of attention. In this case, the same mode of consciousness would be compatible with different distributions of attention. And so a variant of the counterpart argument can be constructed. Two phenomenal episodes that share the same appearances and the same modes of consciousness but have different distributions of attention will be phenomenally distinguishable. On the second horn, consider a view on which the relevant mode of consciousness is (partially) constituted by the nature of attention. In this case, given that attention constitutively involves priority structures, the relevant mode of consciousness must be (partially) constituted by priority structures. But now the mode view will not be a real alternative to phenomenal structuralism. A mode of consciousness that is partially constituted by priority structures will have to be constituted by phenomenal structure (if dualism about phenomenal attention is rejected) since phenomenal structure is determined by priority structure. So, the mode view at best will be an extension of phenomenal structuralism. So, if one accepts the priority structure view about the nature of attention and if the counterpart argument is sound, then phenomenal structuralism seems forced on us.

Let us flesh out this dilemma with some examples.

Consider the view that the alleged attentional mode of consciousness is a conscious thought about the attended object. Wayne Wu has recently suggested such a view.

11

He says

[P]henomenal salience [Wu’s term for the distinctive phenomenal contribution of attention] associated with conscious perception derives in part from cognition: the phenomenal salience of an attended object

9 Equivalently, some speak of supervenience on intentional mode and intentional content (see Crane 2001, 2007).

10 Among others see Crane 2001, 2003; or Chalmers 2004.

11 Wu 2011a, p. 95f. A similar view is also mentioned in Pautz 2010 (and Stazicker 2011a for voluntary attention).

Phenomenal structure or modes of consciousness? 199 correlates with one’s perceptual-based demonstrative thought about it, specifically a demonstrative awareness that one is attending to that object.

On this view, attention cannot make a distinctive phenomenal contribution in the absence of a difference in cognition. The phenomenal difference between attending to the sound of the piano and attending to the sound of the saxophone would consist in thinking that I am attending to this [rather than that] sound.

Wu’s cognitive model seems overly intellectualistic. Consider a first phenomenal episode where the subject’s attention is (passively) drawn to the sound of the saxophone, and a second phenomenal episode where her attention is (passively) drawn to the sound of the piano. Suppose, for example, that her system of psychological saliences has been motivationally penetrated (see the Appendix of

Chapter 6, p. 138 ff): in one case our subject has been rewarded for saxophone sound detection, and in the second for piano sound detection. There could clearly be (and often is) a phenomenal difference between the saxophone episode and the piano episode in such a case of passive attention. But in a scenario like this the subject often will not engage in any form of demonstrative thought. She is not thinking; just listening. Further, consider that a subject might think that she is attending to the computer screen, while in fact she is attending to the scene outside. The phenomenal character of such an experience is partially determined by what one is in fact attending to and not by a thought about what one is attending to (maybe the thought makes an additional phenomenal contribution). These are phenomenal differences that the cognitive model cannot capture.

Now consider as generalization of the cognitive model any view on which attention contributes a mode of consciousness that is distinct from the perceptual mode. Such a view conflicts with what in Chapter 4 (p. 70) I have called the dependency claim: in order to attend to something that thing has to be intentionally given in some attention independent way (you have perceive it, thinking about it, be angry at it, etc.). Any such alleged mode of consciousness thus wouldn’t reflect the nature of attention, and in principle could be instantiated in the absence of attention.

These consideration lead to a view that takes into account those problems. On this view attention isn’t a separate mode of consciousness. Rather it is a determination of other modes of consciousness. Call views in this category mode modification views .

The mode of consciousness contributed by perceptual attention, according to a mode modification view, would be a way of perceptually experiencing the attended object.

Maybe you just perceptually experience something more or less attentively (a sui generis account). Or maybe, attention modifies how much a particular aspect of the subject’s apparent world is phenomenally present to her. On the last view attentional modes of consciousness are determinations of phenomenal presence (arguably the attentively-experiencing view and the degree of presence of are just verbal variants: the object must be phenomenally present in the attention-related way).

200 Phenomenal Structure

Given that attention can look, as it were, inside propositional attitudes (we attend to objects and properties, but not – at least not often – to propositions; see Chapter 5

Sec. 2.3, p. 99 ff), the modes of consciousness that attention modifies will have to be non-propositional modes. Specifically, they are going to be exactly the same mental states that I have called the qualitative parts of a subject’s experience.

What we end up with then is an account of phenomenal structure, and not an alternative to phenomenal structuralism. The best version of the mode modification view says this:

Mode Modification The fact that x

1 intentional object of of x

2 x

1

≻ x

2

is fully determined by the fact that the

has more phenomenal presence as the intentional object

In the end, then, the debate between the view that attention contributes a mode of consciousness and phenomenal structuralism thus isn’t really a debate about intentionalism. For illustration, consider the following two views of conative attitudes: 12 according the view that corresponds to phenomenal structuralism, a subject’s most fundamental conative attitude is preference: she prefers option A over option B. According to the view that corresponds to the mode modification view the most fundamental conative attitude is something like desire: she desires option A more than she desires option B. According to the second view preferences can be reduced to degrees of desire; according to the first view degrees of desire can be reduced to preferences. The difference between those two views has nothing to do with whether “intentionalism about value” is true (i.e. the view that a subject’s values supervene on her intentional attitudes). It is a dispute about relationalism vs. absolutism about value.

The same holds in the present case. The difference between the mode modification view and phenomenal structuralism amounts to a difference between absolutism and relationalism about priorities. It is debate about the nature of attention, and so I refer the reader back to the relevant discussion in Chapter 5 Sec. 2.2 (p. 95). There, I have argued that we should accept relationalism, and it is for this reason that we should prefer phenomenal structuralism over mode modification views (a central reason was that absolutism cannot allow for the possibility of intransitive priorities). We should thus take the centrality relations between qualitative parts (which are determined by priority relations) as our primitive notion and not attempt to reduce it to degrees of phenomenal presence.

5 Centrality systems: center, field, and fringe

Once we have the notion of centrality relations in experience, we can characterize the phenomenal structure of consciousness.

12 See Chapter 5, p.

Centrality systems: center, field, and fringe 201

As our primitive we should take the notion of weak centrality (which will be either weakly or identity mapped to weak priority). We define it as follows.

Weak Centrality x

1

≽ x

2

=

Def x

1

is at least as central in experience as x

2

Weak centrality, like weak priority, is reflexive: every qualitative part will be at least as central in experience as itself.

Two qualitative parts might be equally central, or as I will say co-central in a subject’s experience:

Co-centrality x

1

is co-central with x

2

in experience =

Def x

1

≽ x

2

& x

2

≽ x 1 i.e. both qualitative parts are equally central in experience.

Each qualitative part, of course, will be trivially co-central to itself. But this will not be the only case. Consider watching two objects o

1

and o

2

that spin around each other

(consider also focusing your attention on an electrical plug in its socket). In such a case, two perceptual objects are in the focus of your attention. Both your experience of o

1 and your experience of o

2

are equally central. In cases like this the two cocentral qualitative parts present something like a single Gestalt. But this need not be the case: attention may be split between two qualitative parts even though they do not present a single phenomenal Gestalt.

With weak centrality as our primitive we can also define the anti-reflexive notion of strict centrality with which I originally introduced the idea of the centrality structure of consciousness:

Strict Centrality x

1

≽ x

2

& not ( x

2

≽ x

1

is strictly more central in experience than x

2

( x

1

≻ x

2

) =

Def x

1

) i.e. one qualitative parts is as least as central as the second qualitative part, but the second is not at least as central as the first qualitative part.

Strict centrality has a natural converse. If one qualitative part is strictly more central than another qualitative part, then the latter is in the phenomenal periphery of the former, or – as I will say – is peripheral to the former in the subject’s experience:

Peripherality x

1

is peripheral to x

2

in experience ( x

1

≺ x

2

) =

Def x

2

≻ x

1 i.e. one qualitative part is peripheral to a second qualitative part just if the second is strictly more central than the first.

With the help of the centrality structure we can also make sense of the idea that some part of your experience might be further in the periphery than some other part. While you look at this page with the left L and the right R, and while you focus your attention on L, you might also be visually aware of the edge of your computer screen.

Call your experience of this edge e

Edge

. In this case then: e

L

≻ e

R

and e

L

≻ e

Edge and e

R

≻ e

Edge

. That is, your experience of the edge is peripheral to both your experience of L

202 Phenomenal Structure and your experience of R . In this sense, it is more peripheral than your experience of

R .

We can apply this idea not just within a single sensory modality, but also crossmodally. While you look at the screen, you might be dimly aware of some music in the background. Maybe e

Music

is peripheral even to e

Edge.

In terms of the centrality relation, we can – just like in the case of priority – define the notion of a centrality system , where all qualitative parts are centrality connected to each other (the equivalence closure of centrality).

13

Centrality System Some qualitative parts xx form a centrality system =

Def are centrality connected.

all xx

Centrality systems have some interesting properties.

First, centrality systems are phenomenally unified in the following sense: the qualitative parts of a centrality system will compose a single experience of which they are all parts.

14 There is something it is like to experience those qualitative parts together . This is because weak centrality is an external phenomenal relation, i.e. a relation between qualitative parts that makes a phenomenal contribution that does not supervene on the intrinsic phenomenal qualities of those qualitative parts. There is something it is like to experience x and by what it is like to have x

2 centrality system where x

1 it is like to instantiate x

2

.

≽ x

2

1

≽ x

2

that is not fixed by what it is like to have x

1

. At the same time what it is like to instantiate a

holds does fix what it is like to instantiate x

1

and what

Second, and by the same token, centrality systems are, we might say, phenomenally entangled . What it is like to instantiate a centrality system is not exhausted by what it is like to instantiate the phenomenal qualities of all of it qualitative parts. The phenomenal character of the whole centrality system includes which centrality relations those parts bear to each other.

Because of phenomenal entanglement, centrality systems are more than the sum of their qualitative parts. We can show this by showing that the phenomenal character of a centrality system goes beyond the phenomenal character of what Chalmers and

Bayne 2003 have called the conjunction of its qualitative parts: 15 the conjunction of some phenomenal states xx is a mental state such that necessarily a subject is in that mental state just if the subject is in each of the xx s. Now let S be a centrality system composed of qualitative parts xx , and let C be the conjunction of the xx s. Being in C does not exhaust the phenomenal character of being in S, since C is compatible with a number of phenomenally distinct centrality systems S

1

, S

2

, etc. that differ in the centrality relations that hold between the relevant qualitative parts. And so it is possible to be in C without being in S (in the terminology of Chalmers and Bayne: C

13 The definition parallels the one for the equivalence closure of priority (p. 87).

14 See Chalmers and Bayne 2003, and Bayne 2010a for this notion of phenomenal unity.

15 Following Chalmers and Bayne 2003.

Centrality systems: center, field, and fringe 203 does not entail S; by contrast S does entail C, i.e. it is impossible to be in S without being in C).

In Sec. 8 I will suggest that a subject’s total experience is a single centrality system.

That experience entails all of the subject’s phenomenal states, but is not entailed by the conjunction of its qualitative parts. In Chapter 13 I will argue centrality relations are what builds total experiences or subjective perspectives.

16 For now let us just assume that a subject has a unified experience that forms a single centrality system.

We can now define what it is to be a center of the subject’s conscious experience. The center of the subject conscious experience corresponds to her top priority.

Phenomenal Center A qualitative part x

1

is a phenomenal center of experience E

=

Def

not∃ x ( x is a qualitative part of E & x ≠ x

1

& x ≻ x

1

) i.e. no qualitative part other than x

1

is strictly more central in experience E.

The notion of a phenomenal center has a natural dual. It is naturally called the fringe of consciousness. It is defined as follows.

Phenomenal Fringe A qualitative part x

1

is a phenomenal fringe of experience E

=

Def

not-

∃ x ( x is a qualitative part of E & x

≠ x

1

& x ≺ x

1

) i.e. i.e. no qualitative part is peripheral to x

1

in experience E.

While nothing is more central in the subject’s experience than a center, nothing is more peripheral than what is at the fringe. In our example, your experience of the music might be at the fringe of your consciousness. Just as for the center nothing in the apparatus guaranties that every experience has a phenomenal fringe. Yet, it seems more plausible that experiences all do have fringes and that centrality structure thus is bounded from below.

Between the centers of consciousness and the fringe lies the field of consciousness.

17

We can define it as follows.

Phenomenal Field A qualitative part x

1

lies within the phenomenal field of experience E =

Def

∃ x , y (x and y are qualitative parts of E & x ≠ y & x ≻ x

1

& x

1

≻ y ). i.e. in experience E some qualitative parts are strictly more central than x

1 others are peripheral to x

1

.

and

16 It is thus in Chapter 13 where the (at least for some readers) rather obscure discussion in Chapter 5 (Sec.2.2, p. 95 ff) of whether priority is an internal or an external relation will make a crucial difference.

17 See Chudnoff (2013).

204 Phenomenal Structure

What is in the phenomenal field thus is neither at a center of consciousness, nor is it at the phenomenal fringe. The qualitative parts that are in field of consciousness are peripheral to some qualitative parts and central to some others.

According to phenomenal structuralism, the differentiation of consciousness into center, field and fringe is a structural feature of consciousness. What it is for some qualitative part to be at a center of consciousness or at the fringe of consciousness is given by the centrality relations this qualitative part bears to the other parts of the subject’s conscious experience. The appearance properties of fringe experiences thus need not be characteristically different from the appearance properties of central experiences.

Often, of course, fringe qualitative parts will differ from central qualitative parts also with respect to those appearance properties: attentional priority, after all, as we have seen, is correlated with a variety of effects on the appearances. What is at the fringe of consciousness and what is in the field thus often will present less spatially determinate appearances, or less saturated colors; in some cases temporal resolution will be higher at the fringe compared to the center (in other cases it might be lower).

Given that attention affects feature binding, unbound features that are not experienced as bound to perceptual objects are more likely found in field and fringe experiences than in central experiences. And given that attention affects figure-ground segregation and the experience of perceptual Gestalts, experiences of perceptual figures are more likely found at a center of consciousness than in the field or fringe. None of these correlates of occupying particular positions in a subject’s centrality system should be mistaken though for what it is for an experience to be central, in the field, or at the fringe of consciousness. The correlates will vary from cases to case, are likely different in different sensory modalities, or in different animals. Center, field and fringe are structural and not qualitative features of conscious experience.

6 Phenomenal structure in conscious thought

William James, as we have seen in the quote at the beginning of this chapter, was interested in how attention structures consciousness and in how it contributes to our unique perspectives on the world. Without attention, as we have seen, experience is supposed to be “utter chaos” and only with attention we have an “intelligible perspective.” In other work James says

Accentuation and Emphasis are present in every perception we have

… A monotonous succession of sonorous strokes is broken up into rhythms, now of one sort, now of another, by the different accent which we place on different strokes … The ubiquity of the distinctions, this and that , here and there , now and then , in our minds

Phenomenal structure in conscious thought 205 is the result of our laying the same selective emphasis on parts of place and time.

18

In this quote from James as well as in the examples that I have so far concentrated on, we see how attention structures perceptual consciousness.

Phenomenal structure, though, as James emphasized as well, is not only present in conscious perception. It is present in conscious thought as well.

As a beginning consider what linguists describe as focus marking.

19 Suppose, to use an example from William James (1920), that you are uttering the sentence “Columbus discovered America in 1492.” (maybe you assert it believing it to be true; maybe you use the sentence as an example of biased historiography). An utterance of that sentence might differ in focus or emphasis. There is a difference between (i)

“ Columbus discovered America in 1492”, (ii) “Columbus discovered America in

1492”. One question, one widely studied in linguistics, about the difference between

(i) and (ii) concerns how to theoretically capture the difference in what is conveyed to a listener by the respective utterances.

20 Another question, the one relevant for our present purposes, concerns the phenomenal difference between someone who understands or thinks what is expressed by the respective sentences. That difference is a difference in the respective focus of attention. While the focus of attention is on

Columbus in (i), it is on discovery in (ii). This difference in intellectual attention, just like the difference in perceptual attention, will be associated with difference in phenomenal qualities (maybe you utter “Columbus” sub-vocally a little more loud when you think (i) to yourself?). But those differences in phenomenal qualities are not essential to the phenomenal difference made by focus marking. There will be counterparts that mimic the differences in qualities yet lack the respective attentional structure. In order to capture phenomenal differences in conscious thought we need phenomenal structure, just like we did for conscious perception. In (i) a qualitative part intentionally directed at Columbus will be phenomenally central. By contrast, what is phenomenally central in (ii) will be a qualitative part intentionally directed at the relational property of discovery.

21

William James observed a second element of phenomenal structure in conscious thought. Conscious thought, according to James, does not simply move from one topic or content to another. Any topical thought is surrounded by what he calls a fringe or halo of associated images, feelings, dim memories, etc. Here is one way

James describes this idea.

18 James 1920, p. 170

19 E.g. Rooth 1992.

20 Rooth 1992.

21 See Chapter 5 (Sec. 2.3, p. 109 ff) for how attentional structure and propositional structure may induce distinct divisions in the same mental episode. As far as I can tell the points made in this section about the phenomenal structure of conscious thought do not depend on the view that there is a sui generis phenomenology of propositional thought (as in Pitt 2004). Someone who believes that the phenomenal character of thought reduces to, say, the phenomenal character of sub-vocal inner speech and associated mental images (e.g. Tye & Wright 2011, Prinz 2012) would be able to re-captured most of what I said in terms of the phenomenal structure of that sub-vocal speech and the relevant mental images

206 Phenomenal Structure

Every definite image in the mind is steeped and dyed in the free water that flows round it. With it goes the sense of its relations, near and remote, the dying echo of whence it came to us, the dawning sense of whither it is to lead. The significance, the value, of the image is all in this halo or penumbra that surrounds and escorts it, – or rather that is fused into one with it and has become bone of its bone and flesh of its flesh; leaving it, it is true, an image of the same thing it was before, but making it an image of that thing newly taken and freshly understood.

Let us call the consciousness of this halo of relations around the image by the name of ‘psychic overtone’ or ‘fringe’ 22

To illustrate, let us elaborate our example. If I consciously think the thought that

Columbus discovered America in 1492 I might, for example, have associated images of ships, dim thoughts of the brutal murder of Native Americans, surrounding mental images of slaves, images of festivities at Columbus day, and others. Indeed, the phenomenal difference between those of my readers who cringed at the first use of the Columbus example a few paragraphs ago, and those who read it as just another philosophical example is a difference in exactly that peripheral fringe described by

James.

According to James the significance of a thought in a specific subject’s mental life largely depends on the surrounding psychic overtone. When someone utters the sentence “Columbus discovered America in 1492” whether aloud or sub-vocally what is thought, according to James, has always a “delicate idiosyncrasy” (ibid.), since the

“whole sentence [is] bathed in that original halo of obscure relations, which, like an horizon, then spread about its meaning.” (ibid.).

Phenomenal structuralism helps to explain these Jamesian ideas. The ‘psychic overtone’ or ‘fringe’ are qualitative parts that form the periphery or field of a conscious thought that is at a phenomenal center. What it means for you to think a specific thought (it’s significance for you) largely depends on the associations that are in the periphery of your field of consciousness when that thought is at its center.

In order to show that we indeed need phenomenal structure to account for the phenomenal difference made by the Jamesian fringe, I will draw on an argument by

Anders Nes.

23 Consider three subjects who sub-vocally utter the same sentence. First, there is Ashamed. Her sub-vocal utterance is surrounded by the imagery described above. Second, there is Proud. His sub-vocal utterance is surrounded by a feeling of pride and adventure; images of victorious soldiers; and the like. There is a clear phenomenal difference between Proud and Ashamed. This phenomenal difference consists in a difference in the associated mental images. The explanation of the phenomenal difference between Proud and Ashamed need not appeal to any phenomenal structure. The phenomenal qualities of their respective mental images,

22 James 1920, p. 166 (emphasis in original).

23 Nes 2011. Nes develops the argument in much more detail than I do here. I refer the interested reader to his work.

Center, thematic field, and margin 207 after all, are clearly different too. Let us then consider a third character, Dispirited.

Dispirited has the same mental images as Ashamed. But she does not understand

English: she can parse the sentence ‘Columbus discovered America in 1492’ and subvocally repeat those words. But she does not know what that sentence means. The mental images that surround Ashamed’s thought merely happen to float through

Dispirited’s head while she repeats a sentence she does not understand. There is a clear phenomenal difference also between Ashamed and Dispirited. While Ashamed’s experience has a phenomenal center in whose periphery those images occur (Nes speaks of a theme that unites the relevant mental images), Dispirited’s attention is evenly distributed across those images. There is no phenomenal center to her conscious experience. In order to capture the phenomenal difference between

Ashamed and Dispirited we thus need phenomenal structure in conscious thought

(arguably, we also need to account for thematic unity ; I will turn to this in the next section).

What is in the periphery of conscious thought, just like what is in the periphery of conscious perception, will often be rather indeterminate, or “vague” as James sometimes says. Yet, just like for the case of perception these are mere correlates of peripherality. The Jamesian fringe is constitutively a structural feature of conscious thought and not a matter of vagueness, indeterminacy or un-articulated-ness.

7 Center, thematic field, and margin

So far my characterization of the phenomenal structure of consciousness is rather simplistic. In this section, I will show how to elaborate phenomenal structuralism so as to account for more subtle structural differentiations in a subject’s conscious perspective.

Begin by considering that the distinctions between phenomenal center, phenomenal field and phenomenal fringe are not yet adequate to capture a central idea in James’ notion of the halo of a phenomenal center. James speaks of the halo as “surrounding and escorting” the center. This suggests a form of relevance of the halo of thought to the qualitative part that is at the center. One might plausibly think that not everything that is simultaneously experienced with the conscious thought that Columbus discovered America in 1492 will be part of what surrounds and escorts that center.

Consider a slight headache or my visual experience that accompanies my conscious thought. While these are peripheral qualitative parts, one might think that they are merely peripheral to the center, while the escorting images are experientially more intimately connected to my central conscious thought.

The difference between what is relevant to a central experience and what is merely peripheral was central to the phenomenologist Aron Gurwitsch’s view of the field of consciousness.

24

24 Gurwitsch 2009 [1929].

208 Phenomenal Structure

According to Gurwitsch the field of consciousness is organized into theme, thematic field, and margin. He summarizes the distinction as follows.

The first domain is the theme, that which engrosses the mind of the experiencing subject, or as it is often expressed, which stands in the

“focus of his attention.” Second is the thematic field , defined as the totality of those data, copresent with the theme, which are experienced as materially relevant or pertinent to the theme and form the background or horizon out of which the theme emerges as the center.

The third includes data which, though copresent with, have no relevancy to, the theme and comprise in their totality what we propose to call the margin.

25

Gurwitsch’s theme , then, corresponds to a phenomenal center (or rather: the intentional object of such a phenomenal center). Both what is in the thematic field and what is at the margin of consciousness, by contrast, is peripherally experienced.

Gurwitsch criticizes James for muddling this structural feature of consciousness by confusing it with vagueness or indeterminacy. He says

Suppose we look at a picture hanging on the wall and take the picture as our perceptual theme. At the same time, we perceive, though they are not our themes, other pictures on the same wall, books, papers, the lamp on our desk, the bookshelf on the one side, and the window on the other … The field from which the perceptual theme is singled out and emerges, consists of well circumscribed and delimited things, detached from one another rather than presenting the aspect of a sensible total, devoid of differentiation and structure, as described by

James.

The distinction between what is theme and what is not theme for Gurwitsch like on the present account is an organizational feature of consciousness.

26 Gurwitsch says that he “intend[s] to present a formal invariant of all fields of consciousness”, which is “independen[t] of content” such that “fields of consciousness of highly different descriptions prove isomorphic” 27 to each other.

Gurwitsch’s views about the field of consciousness thus seem roughly aligned with the view I have been proposing. Yet, drawing on and elaborating James’ idea of conscious halos he adds an important distinction that my account has so far neglected.

This is the distinction between thematic field and margin , both of which are in the periphery of a phenomenal center. In the quoted introduction to this distinction, as well as throughout his work, Gurwitsch, like James, draws the distinction between the

25 ibid. p. 4

26 ibid. p. 4.

27 ibid. p. 53.

Center, thematic field, and margin 209 thematic field and the margin of consciousness in terms of what is relevant to the theme.

But what exactly is it for some qualitative part in the periphery to be relevant to a phenomenal center?

There seem to be a number of different aspects to how one qualitative part could be relevant to another qualitative part.

First, the mental images that surround the thought about Columbus form a type of associative cluster.

For a particular subject thoughts about Columbus, images of murder, images of Columbus day festivities, etc. will tend to come together. The relevant images are relevant to the central thought for a particular subject in the sense that images with those phenomenal qualities will tend to co-occur with a central thought about Columbus. By contrast, headaches and visual experiences of a particular office space, while at this moment in the periphery of my Columbus thought, have no general tendency (even for me) to come together with thoughts about Columbus. On a different occasion a central thought about Columbus will be accompanied with similar images but a different visual experience and no headache.

One might thus try to characterize what is in the thematic field of a phenomenal center in terms of what I call the associative periphery of that phenomenal center.

Associative Periphery A qualitative part x

1

of an experience E is in the associative periphery of a qualitative part x

2

just if

(a) x

1

≺ x

2

, and

(b) the phenomenal qualities of tend to be co-instantiated. x

1

and the phenomenal qualities of x

2

The notion of an associative periphery picks out a mixed category: it has a structural aspect ( x

1

≺ x

2

) and it has an aspect related to phenomenal qualities (the association in the phenomenal qualities of x

1

and x

2

). To discover the associative periphery of a subject’s conscious thoughts certainly would amount to discovering a significant aspect of her mental life.

Yet, the notion of an associative periphery seems not enough to capture the intimate way in which Gurwitsch’s thematic field is unified with its center. Consider that, in a specific subject, visual experience of trees will tend to come together with visual experiences of the sky. Sky experiences, for that subject, then plausibly are in the associative periphery of tree experiences. But this may just be because the subject’s environment is set up in this way (trees in front of skies). It is not due to any “delicate idiosyncrasy” of our subject.

Here is a better try. Experiences in the thematic field seem to somehow “color” the central experience (consider also James’ metaphor of “bathing” a thought in its psychic overtone). Because of the different surrounding images, the way Columbus is presented to Ashamed in her experience is different from the way he is presented to

Proud. Gurwitsch describes this as follows

210 Phenomenal Structure

[T] he tinge derived by the theme from the thematic field [is] the perspective under which, the light and orientation in which, the point of view from which, it appears to consciousness… [the thematic field affects] not that which appears, but the mode in which it appears.

28

The central idea thus seems to be that the thematic field affects the way the intentional object of the central experience is presented to the subject. This idea could be developed in a number of ways. Here is a natural one. Let us take the modes of appearance of what is at the focus of attention just as the appearance properties of the relevant phenomenal center. The way Columbus (or his discovery) appears to our subject in her conscious thought about him are the appearance properties of that conscious thought. So, we can define what I call the coloring periphery as follows.

Coloring Periphery A qualitative part x

1 periphery of a qualitative part x

2

(a) x

1

≺ x

2

, and

just if

of an experience E is in the coloring

(b) the fact that x

1

≺ x

2

affects the appearance properties of x

2

What is in the coloring periphery of some qualitative part then will not just be peripheral to that qualitative part but also affect which specific appearance properties this qualitative part instantiates. The coloring periphery is again a mixed category.

Is the notion of a coloring periphery enough to capture Gurwitsch’s idea of a thematic field?

I believe that we need to add something else. Consider that the overall lighting conditions and shadows (of which I am dimly aware) affect the apparent brightness or color appearances of the objects in my surroundings. One might think that my experience of those lighting conditions still is merely peripheral (in Gurwitsch’s margin of consciousness), and not a thematic field for whatever I visually experience.

What needs to be added, I believe, is that what is in the thematic field does not just tend to accompany and color a phenomenal center, but also affects the fact that it is a phenomenal center . The Jamesian fringe of my thought about Columbus sustains the centrality of that thought: I would not keep on intellectually focusing on Columbus were it not for those peripheral images. This is missing in the lighting conditions case: my experience of the lighting conditions affects the apparent color of the desk that is the focus of my attention, but I do not keep on focusing on that desk, because of those lighting conditions. By contrast, my peripheral experience of the clutter of papers on that desk is part of what makes me focus on the desk. What we need is the notion of a sustaining periphery. We can define it as follows.

Sustaining Periphery A qualitative part x

1

of an experience E is in the sustaining periphery of a qualitative part x

2

just if

(a) x

1

≺ x

2

, and

28 ibid. p. 349. See also Yoshimi 2004.

Centrality systems: local or global? 211

(b) if it were not the case that x

1

≺ x

2

E.

, then x

2

would be less central in

Phenomenal centers thus counterfactually depend for their centrality on their sustaining periphery.

We can now define a notion that seems to capture Gurwitsch’s idea of a thematic field as follows.

Thematic Field A qualitative part x

1

of an experience E is in the thematic field of a qualitative part x

2

just if x

1

is in the coloring and sustaining periphery of x

2

.

How important is the notion of a thematic field?

Gurwitsch, as we saw, seems to have thought that thematic fields are an invariant in all conscious experiences.

29 Here is one argument for the view that every experience that has a phenomenal center also has a thematic field that one might extract from

Gurwitsch. One might suggest that the thematic field just is the mode of appearance of the intentional object at the phenomenal center. If that were right, then if every experience presents something under some mode of appearance, then thematic fields must be an aspect of every experience with a phenomenal center.

30

I don’t believe that this argument is convincing. While what is in the thematic field affects the mode of appearance of its center, I fail to see why we should accept that the only sense in which something could be presented with a certain mode of appearance consists in having a certain thematic field. Something could look a certain way to me, even if that way of looking is not affected by what else I experience. I thus reject Gurwitsch’s claim that thematic fields are an invariant in all conscious experiences.

31

Nevertheless, thematic fields are an important aspect of much of our experience. An adequate account of the structure of human experience thus should include them. In addition thematic fields lead to a certain kind of local holism in experience. This holism, while again not present in all conscious experience, is an important aspect of much of our experience.

8 Centrality systems: local or global?

All of the notions discussed in this chapter are relative to a centrality system, i.e. a collection of qualitative parts that are all centrality connected. A phenomenal center is a center of a centrality system, a phenomenal fringe is the fringe of a centrality

29 See also Prettyman 2014, who argues that the relevant structure is present in “all possible perceptual experiences in the actual world” (p. 101).

30 Both Gurwitsch (op. cit.) and Prettyman (op. cit.) make this suggestion (though Prettyman restricts it to perceptual experiences).

31 See Chapter 13 (Sec. 5) for more on modes of appearance and their relationship to the essential character of consciousness.

212 Phenomenal Structure system, a thematic field is a field within a centrality system, etc. How big are those centrality systems?

Just like for the case of priority systems, big centrality systems may have interesting parts that are also centrality systems. We may, for example, consider a subject’s visual centrality system that includes all and only the qualitative parts of the subject’s visual experience. There may be a phenomenal center within that visual centrality system to which all other qualitative parts of the subject’s visual experience are peripheral, which is not a phenomenal center of a larger centrality system that extends the visual system. When you are the Jazz concert your visually most central experience might be your visual experience of the saxophone player, even thought that visual experience is peripheral to your auditory experience of the sound of the saxophone. Do subjects have several distinct centrality systems that are not extendable to a single all-encompassing centrality system?

When I have discussed the size of priority systems, I argued that the evidence is most consistent with the claim that subjects normally have a single priority system. Does this show that subject’s also have a single centrality system? Almost, but not quite.

Suppose that there is unconscious attention (as there is, see Chapter 12). In this case a priority system may have, as we might say, phenomenal holes : psychological parts that do not instantiate phenomenal qualities. Indeed such a phenomenal hole might be of top priority, when the subject focuses attention on something that she is not consciously aware of. A priority connected priority system with a phenomenal hole might not be centrality connected. Priority connectedness might be established only through the unconscious psychological part – an unconscious connector as we might call it. Most phenomenal holes will not be unconscious connectors. Centrality relations will, as it were, flow around that phenomenal hole: all the qualitative part s of the priority system will remain centrality related to each other even though some parts of that priority system are phenomenal holes. I take it that this is what happens in the cases of unconscious visual attention I will discuss in Chapter 12: while the subject is not conscious of the focus of her attention, the parts of her visual experience she is conscious of are all centrality related to each other. For now I will assume that there aren’t any unconscious connectors and that subjects thus have a single centrality system. I will return to the relevance of this assumption in Chapter

13 when I discuss the relationship between attention and consciousness in detail.

9 Phenomenal holism?

32

Centrality systems, as we have seen, form a phenomenally unified and phenomenally entangled whole. In the closing section of this chapter, I will consider the question whether phenomenal holism follows from this entanglement.

Before we can answer this question, let us get clear on what the question actually is. I will assume that both the relevant phenomenal whole (the centrality system) and its

32 This section is largely drawn from Watzl 2014a. [CHECK]

Phenomenal holism? 213 qualitative parts exist . Whether holism is true concerns what is more fundamental: the qualitative parts or the phenomenal whole?

33

To illustrate, consider again Franz Brentano’s two hemispheres of a spherical indivisible atom.

34 These are the kind of part that exists only in virtue of the whole of which they are parts. They are not independent existents, out of which the whole is constructed, but mere abstract divisions within the whole. A heap of some pebbles, by contrast, seems different. Here it is the heap that exists in virtue of the existence of the pebbles. Its existence is fully explained by the existence of the pebbles and not the other way around. So are the qualitative parts of a centrality system more like the pebbles or more like the hemispheres?

Let us then consider whether the following thesis is true.

Centrality System Holism The fact that a qualitative part of a centrality system exists is grounded in the fact that this centrality system exists.

If centrality system holism were true, and if a subject’s total experience indeed is a single centrality system (as suggested in the previous section), then phenomenal structuralism would lead to phenomenal holism, i.e. the view that the parts of a subject’s experience exist in virtue of the fact that her whole experience exist. This, certainly, would be an interesting claim (a view like this, indeed, has been defended in recent work by Elija Chudnoff).

35

To see whether centrality system holism is true, let us start by asking whether phenomenal structuralism is consistent with the following atomism about consciousness.

Phenomenal Atomism The fact that a phenomenal whole exists is fully grounded in the fact that the qualitative parts that compose that whole exist.

According to phenomenal atomism the existence of phenomenal wholes can be fully explained in terms of facts about their parts. The idea thus is that once we have a particular collection of experiences, there is nothing more to the whole than is already given by the parts.

Atomism plausibly implies a modal claim. If the existence of the whole is fully grounded in the existence of the parts, then each of these parts could have existed without the whole (because – given the asymmetry of grounding – its existence does not depend on the existence of the whole). This form of atomism thus is one way of articulating what might be meant by Hume (1739/2000) when he said that what we call a mind, is nothing but a heap or collection of different perceptions … every perception … may be consider’d as

33 See Schaffer 2010 and Lee forthcoming for this way of formulating the question.

34 Brentano 2012 [1874], p. 121ff

35 See Chudnoff 2013.

214 Phenomenal Structure separately existent … there is no absurdity in separating any particular perception from the mind 36

If some experiences form a centrality system, then phenomenal atomism cannot be true of them. For there is more to the whole than the parts, namely the structure of centrality relations that connect them. This is entailed by phenomenal entanglement.

In the stack image: you cannot know just by considering each book in a stack which one will be on bottom and which one on top. The order of the books is an additional piece of information you will need in order to account for the whole. Phenomenal structuralism thus is inconsistent with phenomenal atomism.

Someone might object: but aren’t the phenomenal centrality relations themselves qualitative parts of centrality systems? If so, then it would seem that phenomenal atomism could be rescued.

In reply, consider first that in the end (Chapter 13) I would like to argue that centrality relations are what builds conscious perspectives. If that is so, then we should not consider them to be parts of the phenomenal whole. For comparison consider the following (see Johnston 2006). Consider that hydrochloric acid molecules are formed by a chemical bonding relation between a hydrogen and a chloride ion. Is the chemical bonding relation a part of this hydrochloric acid molecule? If so, vicious regress threatens: in order to form a whole the two ions need to be bound by chemical bounding. But what binds the chemical bounding part to the two ions? We would need another binding relation. But by the principle that suggested that chemical bonding is part of the molecule, this new binding relation would seem to be a part of the whole too. So, we need another one. Etc.

37

Second, even if we were to think of centrality relations as parts of centrality systems, they would not be qualitative part s. The holding of a centrality relation between two qualitative parts is not modally separable from those qualitative parts. It cannot – as a phenomenal relation – exist independently of its relata: the relation depends for its phenomenal contribution on something that it relates, and so unlike the relata it is not an independent experience that “may be consider’d as separately existent” (Hume, op. cit.).

So, we are right to reject phenomenal atomism.

Does the rejection of atomism imply centrality system holism? No. Consider our stack of books again. It would be wrong to think that the existence or identity of the individual books, for example, depended on the whole in which they are stacked. But the stack isn’t a mere plurality of books either. The stack is a structured plurality. In order to account for facts about the whole, we need the facts about the parts as well as

36 Hume 1739/2000, sec. 1.4.2, p. 137f

37 This, of course, just is a version of Bradley’s regress (for recent overview of such solutions see Maurin 2012). There might be ways of solving this issue (e.g. to say that the bond of instantiation of properties and relations by particulars does not need a further principle of unity).

See Paul (2002).

Phenomenal holism? 215 the facts about the relations between the parts. This suggests an attractive picture for how to think about centrality structured experiences. It is the following.

Phenomenal Construction The phenomenal properties of a centrality system S are fully grounded in (a) the phenomenal qualities of the qualitative parts of S, and

(b) the centrality relations between those parts.

Phenomenal construction is compatible with both the claim that centrality connectedness is a contingent feature of experiential wholes, as well as with the claim that it is an essential feature of such wholes. On the contingency conception, attention is a mental capacity that is distinct from the capacity for experience. It simply adds structure to experience. On the essentialist conception, by contrast, the capacity for attention would be essential for the capacity for experience. Attentional structure would be for experience what chemical binding is for molecules. It is part of what it is for something to be an experience.

I will argue for the essentialist conception in Chapter 13. What matters for present purposes is that on either interpretation phenomenal construction is not a form of holism: the existence or identity of the books is independent of the stack in which they are embedded; and the existence and identity of a molecule’s atoms is independent of the molecule of which they are a part. Similarly, the existence of the parts of a centrality system would be independent of the centrality system in which they are embedded. The relata of a centrality system (the experience of the saxophone, the experience of the itch, etc.) thus could have existed without that centrality system, and so they are not grounded in the existence of the centrality system.

Chudnoff (2013) offers an argument that the phenomenal construction claim is mistaken. I will now consider this argument.

The argument is based on a phenomenological observation. Think of one specific peripheral experience of the sound of a saxophone. This experience has a highly specific phenomenal character. There is the specific subjective loudness and timbre of the saxophone, the particular distance at which I am experiencing it, etc. Further, and importantly for present purposes, it seems that the peripherality of the experience strongly contributes to its phenomenal character as well. It would seem to have been a quite different experience, had I focused my attention on the saxophone instead of focusing it on my itch. For this reason Chudnoff thinks that it is plausible that “an experience has its phenomenal character in part because of its location in the centrality ordering [=centrality system].” 38 On the basis of this phenomenological observation Chudnoff holds the following.

Phenomenal Holism The fact that a qualitative part has the phenomenal properties it has is partially grounded in the fact that it has a specific position in a centrality system.

38 Chudnoff, op. cit., p. 572.

216 Phenomenal Structure

We have seen above that attentional connectedness is an external relation, i.e. its instantiation is not fully grounded in the intrinsic properties of the relata. If this is true, and if phenomenal holism is also true, then the phenomenal properties of an experience cannot in general be intrinsic to it since they depend on its centrality relations to other experiences. The phenomenal character of each experience in a centrality system will be partially determined by its position in the centrality system.

The parts of a total experience thus would turn out to be a little bit like monads – carrying within them already the whole system. Each of them would have had a different phenomenal character if even one of them went out of existence.

Chudnoff continues his argument for holism with the assumption that its phenomenal properties are essential to an experience. That is: with different phenomenal properties it would be a different experience. This assumption is plausible (it also follows if we individuate experiences as triples of phenomenal properties, subjects and times). So, its phenomenal properties are essential to an experience but not intrinsic to it. Centrality thus, on Chudnoff’s view, turns out to be a relation that while external is essential to its relata. Schaffer (2010b, p. 349) calls such relations internal essential

. He defines the notion as follows:

Internal

Essential

R is internal essential exists iff Rx

1

… x

N

) & … &

=

Def

( x

N

∀ x

1

… x

N

(if Rx

exists iff Rx

1

… x

N

1

…

))) x

N

then necessarily (( x

1

And so each qualitative part of a centrality system exists only if the centrality system exists. We thus have holism.

On Chudnoff’s conception none of my current experiences could have existed with even the smallest difference in my attention. For each experience, its position in the centrality system in which it is embedded is essential to it.

This might seem too strong, even if one is attracted to the general picture. The position can be weakened though, and holism might still follow. Consider the claim it is essential to a fringe experience that it is a fringe (and so nothing is peripheral to it), while its exact position in the centrality system is not essential to it (it is not essential, for example, how many other experiences are less peripheral than it, or whether exactly one experience is central). Generally, one might hold – following Chudnoff’s line of thought – that it is essential to the phenomenal character of an experience whether it is a phenomenal center, in the phenomenal field or at a phenomenal fringe.

Since each experience is either center, field or fringe, we would have modal constraints on any two experiences within a centrality system. Consider a central itch experience e c

and a field-like saxophone experience e f

: there is no possible situation in which both e c and e f