CLIMATE MODELS AND THE VALIDATION ... GREENHOUSE CHANGE THEORY by 1983

advertisement

CLIMATE MODELS AND THE VALIDATION AND PRESENTATION OF

GREENHOUSE CHANGE THEORY

by

James S. Risbey

University of Melbourne

1983

M.Sc., Massachusetts Institute of Technology

1987

B.Sc.(Hons),

Submitted to the

Center for Technology, Policy, and Industrial Development

in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of

MASTER OF SCIENCE

IN TECHNOLOGY AND POLICY

at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

February

©

Signature

1990

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 1990

of Author

Center for Technology, Policy and Industrial Development

tmospheic, and Planetary Sciences

Department of Earth,

February 14, 1990

Certified

byJudith Kildow

Thesis Supervisor

Certified by

Peter

Thesis

Accepted

by

Stone

Supervisor

Richard de Neufville

Chairman, Technology and Policy Program

K-A

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank my advisors, Peter Stone and Judith Kildow for

their longstanding support and guidance, and for providing the necessary

direction and emphasis to ensure completion of the thesis. Thanks are also due

to them for giving attention to the thesis, often under short notice, while I was

I am grateful to Mark Handel and Chantal

attempting to meet final deadlines.

Rivest who have been great resources and officemates, as well as suppliers of

Bill Clark

the necessary quantity of fine chocolate for working on a thesis.

and Tad Homer-Dixon were also important sources of resources and feedback.

and other students in the International

Peter Cebon, Peter Poole,

Environmental Issues Study Group have provided helpful stimulus in various

I thank my family for their support

ways throughout the course of the work.

Linda Murrow, Jane McNabb, Tracey Stanelum, and Daniel

from afar.

Leibowitz also provided invaluable support.

Funding was generously provided by NASA Goddard Institute for Space

Studies (GISS) for this research under grant 'NASA /G-g NSG 5113', and I am

GISS director James Hansen in particular was most

indebted to them.

understanding in continuing to provide financial support while I registered

in the Technology and Policy Program, which was a digression of sorts from

conventional straight science projects carried out in the department.

A number of people provided data and data support for this project, and

They include Bill Gutowski, W.C. Wang and

I am very grateful to them all.

David Salstein of AER, who provided most of the NCAR, GFDL, and GISS GCM data.

Reto Reudy of NASA GISS provided energy transport data, flux data, and

Richard Wetherald of GFDL provided

topographic data for the GISS GCM.

Robert Black of MIT provided topographic

additional data for the GFDL GCM.

data for the NCAR GCM. I thank NCAR, GFDL, and GISS GCM modelling groups

for allowing me to use output from their models.

CONTENTS

6

ABSTRACT

-7

LIST OF FIGURES

LIST OF TABLES

10

GLOSSARY OF PRINCIPAL SYMBOLS

11

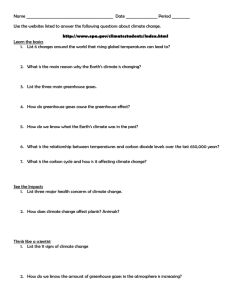

1.

1.1 Intent,

2.

12

INTRODUCTION

and thesis

background,

definition

20

GREENHOUSE THEORY

2.1 Greenhouse

effect

20

2.2 Greenhouse

change

21

23

2.3 Climate models and climate

3.

experiments

2.4 Greenhouse

change

modelling

2.5 Greenhouse

change

controversies

2.6 Greenhouse

problems

24

26

33

VALIDATION OF CLIMATE MODELS

34

3.1 Approach

34

validations

3.1.1

Internal

3.1.2

Perturbed-run

3.1.3

Control-run

validations

validations

3.2 NCAR, GFDL, GISS model validations

3.3 Energy

4.

12

validations

transport

38

40

43

46

hierarchies

4.2 One-dimensional

36

46

MODEL DESCRIPTIONS

4.1 Model

35

energy

4.3 NCAR, GFDL, GISS models

balance climate model

47

50

5.

DATA

53

5.1 Climate model output

53

5.2 Observational

5.3 Surface

5.4 Sea

energy

56

derivation

temperature

5.4.1

Lapse rate data

5.4.2

Topographic

5.4.3

Sea level

56

57

data

57

temperatures

5.5 Satellite data

58

5.6 Sea ice data

58

5.7 Journal literature

6.

56

data

air temperature

level

55

data

transport

and media

59

accounts

VALIDATION OF MODEL FUNDAMENTALS: ENERGY TRANSPORT

61

6.1 Energy transport and its role in climate

61

6.2 Procedure to calculate energy transport in the models

6.3 Comparison of direct and indirect transport calculation

62

method

66

6.4 Results

7.

65

6.4.1

Annual radiative fluxes at the top of the atmosphere

6.4.2

Energy

6.4.3

Atmospheric

energy

6.4.4

Temperature

structure

66

68

transports

71

transports

73

MODEL CLIMATE SENSITIVITY

76

7.1 Introduction

76

7.2 Climate sensitivity to the energy transport

77

7.3 Equivalent

79

EBM parameterization

7.3.1

Parameterization

7.3.2

Mean annual

79

technique

meridional distribution

of solar radiation

80

and solar constant

7.3.3

Iceline latitudes

7.3.4

Outgoing

7.3.5

Albedos

and sea level temperatures

longwave

7.4 Equivalent EBM results

7.5 Discussion

7.6 GCM validation implications

radiation

_81

82

83

_85

89

90

5

8.

GREENHOUSE CHANGE VALIDATION FRAMEWORK

96

8.1 Introduction

96

outline

8.3 Validation

components

103

8.3.1

Uncertainty

105

8.3.2

Credibility

107

8.3.3

Useability

110

8.4 Greenhouse

9.

97

8.2 Framework

change

characteristics

112

GREENHOUSE CHANGE VALIDATION PRESENTATIONS

116

9.1 Introduction

116

9.1.1

Approach

118

9.1.2

Background

119

9.2 Discussion of scientific papers on or implicated in detection of

greenhouse

change

9.3 Characterization

9.4 Science

of the media coverage

presentation

9.4.1

General

9.4.2

Scientific

9.5 The

121

standards

guidelines

science-media

standards pre and post presentation

interface

9.6 Conclusions

130

131

131

133

138

139

10. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

142

FIGURES

147

REFERENCES

178

CLIMATE MODELS AND THE VALIDATION AND PRESENTATION OF

GREENHOUSE CHANGE THEORY

by

JAMES S. RISBEY

Submitted to the

Center for Technology, Policy, and Industrial Development

in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of

Master of Science in Technology and Policy

ABSTRACT

We identified problems in validating greenhouse change theory

We focused on GCMs, noting the heavy reliance

science-policy context.

As a case study

3-D GCMs for developing greenhouse change scenarios.

validation, we analysed simulation of energy transports in the three

GCMs used in greenhouse climate studies of NCAR, GFDL, and GISS.

in a

upon

GCM

major

Comparison of energy transports in the GISS GCM calculated directly

from model motions and indirectly from the net flux of radiation at the top of

The

the atmosphere indicated that the indirect technique is satisfactory.

atmospheric energy transports calculated using the indirect technique were

found to be similar in all GCMs, but too efficient, being much larger than

For the total energy transports significant differences were

observations.

obtained between the three GCMs in the NH, with NCAR and GFDL less than

We used a 1-D EBM to

observations and GISS greater than observations.

demonstrate that the climate is potentially quite sensitive to the energy

To test implications of the differences in energy transport between

transport.

GCMs, we parameterized the EBM with output from the GCMs and observational

Using an increase of solar constant by 2% as a

data, separately in each case.

proxy for CO 2 doubling in the EBMs, similar sensitivities were obtained

between equivalent EBM representations for each GCM and with the GCM

The differences in energy transport between GCMs

doubled CO 2 sensitivities.

were apparently compensated for in the equivalent EBM representation,

though the sources of compensation are not yet clear.

We described a framework for validating GCMs and greenhouse change,

comparing and contrasting the approach and requirements of science and

We noted potential mismatches in operation and

policy communities.

requirements between the communities, and the current inability to

We

incorporate uncertainties in critical evaluation of greenhouse change.

considered communication of validation information from science to policy by

Instances of

analysing science journal literature and its media interpretation.

to a

partly

attributed

and

identified

were

media

the

in

misinterpretation

journal

the

in

audience

a

broader

to

appropriate

context

failure to provide

We argued that the addition of context is required when science

literature.

journal literature has clear policy implications and is undergoing scrutiny by

the media.

Thesis Supervisors: Dr. Judith Kildow and Dr. Peter Stone

Titles: Professor of Technology and Policy, and Professor of Meteorology

LIST OF FIGURES

5.1

Zonal mean 850mb - 950mb lapse rate from Oort (1983) data

147

5.2

GISS topography on the GISS grid

148

5.3

NCAR CCM1 R15 surface geopotential height

149

5.4

NCAR (N) and GISS (G) zonal mean topography

150

5.5

NCAR (N), GFDL (P), and GISS (G) control run surface

temperatures (solid lines) and sea level temperatures

(dashed lines)

151

6.1

Annual mean zonal mean total meridional (northward) energy _152

transport (T), atmospheric energy transport (A), and ocean

energy transport (0) for Carissimo et al. (1985) observations

(dashed lines), and calculated directly from the GISS control

run model motions (solid lines)

6.2

Annual mean zonal mean total northward energy transport

calculated directly from the GISS model motions (D), and

indirectly from the net flux of radiation at the top of the

atmosphere in the GISS model (I) (control run)

153

6.3.16.3.6

Annual mean zonal mean shortwave flux at the top of the

atmosphere (SWTP), longwave flux at the top of the atmosphere

(LWTP), shortwave flux at the surface (SWSF), longwave flux at

the surface (LWSF), sensible heat flux at the surface (SHSF),

and latent heat flux at the surface (LHSF) for the NCAR (N1,N2),

GFDL (P1,P2), and GISS (G1,G2) models. The numbers '1' and '2'

refer to equilibrium results for 1 x CO 2 and 2 x CO 2 simulations

154

6.3.7

Annual mean zonal mean net radiative flux at the top of the

atmosphere from NCAR (N), GFDL (P), and GISS (G) model

control runs, and from Stephens et al. (1981) observations (0)

156

6.4.16.4.3

Annual mean zonal mean total northward energy transport for

NCAR, GFDL, and GISS models (control run). The curves

labelled 'N' are for integrations starting at the north pole, the

curves labelled 'S' are for integrations starting at the south

pole, and the curves labelled 'C' are corrected curves. The

dashed curve is from Carissimo et al. (1985) observations (0)

157

6.4.4

Corrected annual mean zonal mean total northward energy

transport for NCAR (N), GFDL (P), and GISS (G) models (control

run), and for Carissimo et al. (1985) observations (0)

_157

6.5

Annual mean zonal mean northward atmospheric energy

transport for NCAR (N), GFDL (P), and GISS (G) models (control

run), and for Carissimo et al. (1985) observations (0)

_158

7.1

Iceline latitude (xs) versus ratio of the solar constant to the

current solar constant (q/qo) for the 1-D EBM

159

7.2

Meridional energy transport flux as a function of the sine of

latitude (x) for the 1-D EBM

160

7.3.17.3.3

Maximum energy transport flux, second component of

outgoing longwave radiation (I2), and iceline latitude (xs) as

functions of the dynamical transport efficiency (D) for the

1-D EBM

161

7.4

Iceline latitude (xs) for NCAR (ncarnh, ncarsh, ncargl), GFDL

(gfdlnh, gfdlsh, gfdlgl), and GISS (gissnh, gisssh, gissgl)

models (control run), and from Alexander and Mobley (1976)

observations (obsnnh, obsnsh, obsngl).

In each case, 'nh' is

for the Northern Hemisphere, and 'sh' is for the Southern

Hemisphere.

The global (gl) values are averages of the

hemispheric values in each case

162

7.5

As in fig. 7.4, but for the sea level temperature at the iceline

latitude.

Temperature observations are from Sellers (1965)

162

7.6.17.6.6

Annual mean zonal mean planetary albedo (ALBEDO), net

flux of longwave radiation at the top of the atmosphere (I),

and sea level temperature (T) for NCAR (N), GFDL (P), and GISS

(G) models (control run), and from Stephens et al. (1981)

observations (0 for Albedo and I) and Sellers (1965)

observations (0 for T). The curves are plotted separately for

the Southern Hemisphere (SH) and Northern Hemisphere (NH)

as a function of the sine of latitude (x)

163

7.7.17.7.2

As in fig. 7.4, but for parameterized values for A and B from the

temperature - outgoing longwave radiation parameterization

I = A + BT in the equivalent EBMs.

164

7.8.17.8.2

Parameterized outgoing longwave radiation (I) as a function of _165

the sine of latitude in Southern and Northern Hemispheres (SH

and NH) for NCAR (N), GFDL (P), and GISS (G) models, and for

observations (0). I is calculated via I=A+BT with the

parameterized A and B values and with the actual zonal mean

temperatures for each case (not with the two mode Legendre

representation of the temperature)

7.9.17.9.3

As in fig. 7.4, but for parameterized values for the albedo

components ao, a2, and 8 in the equivalent EBMs

7.10.1Parameterized albedo as a function of the sine of latitude (x) in

7.10.2 Southern and Northern Hemispheres (SH and NH) for NCAR (N),

GFDL (P), and GISS (G) models, and for observations (0)

7.11

Outgoing longwave radiation at the iceline latitude (Is) from

each of the twelve equivalent EBMs

166

167

168

7.12

Dynamical transport efficiency (D)

equivalent EBMs

from each of the twelve

168

from

169

Outgoing longwave radiation components

7.13.17.13.2 each of the twelve equivalent EBMs

Temperature components

7.14.17.14.2 equivalent EBMs

(I)

and (12)

(TO) and (T 2 ) from each of the twelve

170

Sea level temperature from the original NCAR, GFDL, and GISS _171

7.15.17.15.8 GCMs and observations (solid lines), and calculated via the

equation T(x)=To+T 2 P 2 (x), where the To and T2 have been taken

from the equivalent EBMs (dashed lines). The results are

plotted as a function of the sine of latitude (x) for each

hemisphere

7.16

Energy transport flux maximum from the equivalent EBMs

(solid bars) and from the original GCMs and Carissimo et al.

For the latter the global

observations (cross hatched bars).

'gl' values are averages of the hemispheric values

172

7.17

Iceline latitudes (xs) as input to the equivalent EBMs in each

case (solid bars), and as calculated in the equivalent EBMs

when the solar constant was increased by 2% in each case

(cross hatched bars)

173

7.18

Climate sensitivity calculated from the equivalent EBMs

174

8.1

Greenhouse

change

validation

framework

175

10

LIST OF TABLES

5.1

Latitudinal spacing of the zonal mean data in the NCAR, GFDL,

and GISS models, in Carissimo et al. (1985) observations, and in

Sellers (1965) observations (NO and S*)

6.1

Sea level temperatures

at 550 and 25* in each hemisphere

_

60

_

75

_

95

derived from GCMs and Sellers (1965) observations. AT is the

temperature difference per degree of latitude over this range

of latitudes

7.1

In each

Inputs and outputs from the twelve equivalent EBMs.

case the first four letters denote the model or observations, and

the last two letters denote the hemisphere (Northern

Hemisphere or Southern Hemisphere) or average of the

Results are given for both the current

hemispheres (Global).

The

solar constant and for the solar constant increased by 2%.

climate sensitivity calculated for each case is also shown

GLOSSARY OF PRINCIPAL SYMBOLS

symbols of physical

The principal

and mathematical

quantities used in

Some symbols formed from principal symbols by

this report are listed below.

adding subscripts, and others that are used in only one place are not listed.

Some quantities are denoted by two different symbols for clarity of notation in

Usage should be unambiguous in any given section.

different sections.

Symbol

Name or Definition

a

Radius of the earth

A

Longwave

-

temperature

parameter

B

Longwave

-

temperature

parameter

D

Dynamical

transport

F

Meridional

energy

FTA

Net downward flux of radiation at the top of the atmosphere

Hn

Insolation

I

Outgoing longwave radiation at the top of the atmosphere

Pn

Legendre

q

Solar

R

Radius of the earth

S

Meridional

T

Sea

TT

Total

x

Sine of latitude

z

Geopotential

a

Albedo

efficiency

transport

flux

component

polynomial

constant

distribution

of solar radiation

level temperature

meridional

Climate

Lapse

energy

transport

height

sensitivity

rate

parameter

6

Albedo

0

Latitude

a

Stefan

<p

Longitude

- Boltzmann

constant

12

1

definition

thesis

and

background

Intent,

1.1

INTRODUCTION

theory, its validation

The subject material for this thesis is greenhousel

here

to

to

refer

the

of whether

question

in

changes

with

associated

is used

theory

the

We consider the problems associated with the

and

science

greenhouse

support policy

to

enough

from

obtained

the information

is credible

models

Greenhouse

presentation.

of knowledge

body

greenhouse effect.

atmospheric

climate

and subsequent

models,

in climate

Long

decisions.

the

domain of the scientist, greenhouse theory is now also part of the purview of

the politician,

the policy

analyst,

The

examines

thesis

of

problems

involves

the

growing

links

between

theory

greenhouse

validating

link between

basic

in developing

greenhouse

in

and

science

policy

about

of thinking

for the purpose

a framework

and

scientific

the

communication

validation

in

process

science

of validation information

etc.)

is uncertain,

from

given to assessing how well

scientists

arenas

supports

theory,

what is knowable,

Attention

to policymakers.

scientific information

and policy

(what

what undermines theory, what is known, what is unknown,

what

change

greenhouse

in validating greenhouse change theory in science and policy.

issues involved

A

the

will present

We

domains.

used

proletarian.

and the

These links will be highlighted through a consideration of

greenhouse policy.

the

models

climate

and explores

scenarios,

owner,

the property

on validation

will be

is presented

to the policy community.

The

impacts

associated

with

current

greenhouse

small part of the greenhouse issue is considered.

change

policy measures

implemented

in

from

We examine the theory of

the point of view of what matters

involving public expenditures

response

to

require some justification to act.

greenhouse

are

In the thesis however, only a

potentially serious, and warrant much attention.

greenhouse

predictions

for policy.

and lifestyle changes

predictions,

They will need

tw

then

If

are to be

policymakers

know if the theory

is

1The term 'greenhouse' is objectionable to some, primarily on the grounds that the physics associated

with the workings of a glass greenhouse are not very analogous to those associated with the atmospheric

The term is widespread however, and the analogy does have some merit (see

greenhouse effect.

discussion in Bohren, 1987), so its usage will be continued here.

13

from

predictions

the

whether

is

that

'valid';

theory

the

are

and

credible

A climate model is valid to the extent that it is plausible and produces

At some other levels of

results at some levels of aggregation that are useful.

aggregation the results will not be very useful because the model is not

designed to resolve certain scales or processes, or contains assumptions that do

useful. 2

not

we

as

set

implicitly

In a validation

under certain conditions.

hold well

to

seek

are

range

of

any

is

there

whether

determine

study, bounds

3

aggregation of output results that can be considered credible and useful.

thesis,

this

In

analysis

largely

confined

be

will

the

to

of

issue

credibility, and we will not consider actual policies that might be implemented

The credibility of greenhouse theory with

in response to greenhouse change.

regard to policy has not been directly addressed since beginnings were made

in U.S. National Academy of Science reports in 1979 and 1982 (NRC, 1979/1982).

that

Given

greenhouse

of credibility

assessment

of credibility,

varying degrees

accord

scientists

different

predictions

with

by non-scientists

in

No attempt is made to answer the

the policy domain is bound to be difficult.

That assessment largely

question of credibility definitively for policy makers.

boils

to

down

collectively

greenhouse

judgement,

the problems

and

science

value

by interpreting

on

focus is

a

policy

issue

that

available

be

must

made

be

knowledge through

of assessing

arenas,

can

and

credibility

and

on

identifying

used

by

science

individually

value systems.

of greenhouse

and

characteristics

policy

and

The

theory

in

of

the

communities

to

establish a basis for examining policy credibility.

Greenhouse

of uncertainty,

scientists

warming is a complex issue characterized by a high degree

making policymakers particularly sensitive to the way that

present information

relevant to establishing

credibility

in the issue.

Scientific inputs initiate the policy process, alerting society to the existence of

a problem (potential greenhouse warming) and the need for policy responses.

We take a practical approach (considering what is useful) rather than a philosophical approach (i.e.

can a model or theory ever be validated) to the problems of validating theory, since this is more

immediately applicable to the policy making process.

3

This definition is general enough to apply to validation in science or policy arenas, though in science

it may occasionally be irrelevant, since we are sometimes only interested in understanding processes

in models and do not care about the validity of the results otherwise.

2

1

Introduction

14

Once a scientific issue takes on policy dimensions

research

further scientific

is stimulated and the results continue to filter through to the policy

The presentation of these results shapes the policy process by

bolstering

or

We

response.

the perception

reducing

will

carry

to

attempt

been

have

of the

problem

presenting

in

which

scientists

greenhouse

change

theory to the policy community.

manner

assessment

validation

problems

in

encountered

assessing

the

a

of the

information

in

The first is to

Thus far, essentially two tasks have been constructed.

highlight

either

case for

and the

out a preliminary

arena.

credibility

of

greenhouse

and policy arenas, and to identify links to facilitate closer

To this end, the second task

coupling of information between the two arenas.

involves assessing how well scientists are doing at translating knowledge on

validation of greenhouse theory from the scientific domain to the public

theory in scientific

domain.

This

consideration

is

still

far

too

of fundamentals in

broad,

so

the hope

we reduce

both

problems

that narrow but basic

to

a

approaches

to the problem serve some utility.

Assessing the credibility

of greenhouse theory from

the point of view

of policy entails analysing the nature of predictions from the theory, since it

is the predictions that are the ultimate input of the science to the policy

For greenhouse theory, the 'prediction inputs' to policy take the form

4

of 'how big a temperature rise or precipitation change, how fast, and where?'

By and large, these predictions come from three-dimensional general

5 As

circulation climate models (hereafter simply 'climate models' or 'GCM's').

process.

More correctly, it is probably the impacts on social systems associated with these predictions that is

meaningful to policy makers, and not so much the predictions themselves. In other words, 'so what if

In practice however, the impacts are incredibly

the temperature rises five degrees on average?'

In addition,

difficult to determine accurately, and add another layer of uncertainty to the problem.

the predictions from the models are by no means totally uniform, so that it is difficult to agree on a

climatic scenario on which to study impacts. For these and other reasons, policymakers still find it

useful to focus on the raw climatic predictions.

5

The terminology is a little confusing, since 'GCM' is used to refer to both general circulation weather

models used in weather forecasting, and general circulation climate models used in climate studies.

Though the two types of models have many similarities (indeed, some climate models are modified

The differences stem from the need to consider

weather models), there are also crucial differences.

different time scales and therefore different physical processes in one type that are not important in

the other type. In this work, the usage of GCM as climate model is always intended. Sometimes climate

models are further classified as atmospheric (AGCM) and oceanic (OGCM), or as a coupled oceanatmosphere GCM.

4

1

Introduction

15

noted

in the

thesis, in a philosophical

sense the predictions

(and levels

of

confidence associated with them) are not purely the result of the 3-D GCMs.

Input to the 3-D models and interpretation of the results is aided by a host of

simpler

changes

is

it

however,

past

of

observations

to

necessary

a

use

GCM

climatic

about future

quantitative predictions

In order to make reasonable

behaviour.

climatic

and

reasoning,

physical

models,

to

incorporate

anything like the full degree of complexity of the climate system. 6

(1983)

that

notes

of

use

assessment

comprehensive

necessary

for

a

mechanisms

feedback

Hence,

climate change.

distribution of greenhouse

Congressional

of various

influence

of the

is

of climate, as well as for simulating the latitudinal

upon the sensitivity

geographical

GCM's

three-dimensional

Manabe

and

much of the

on greenhouse change has been by GCM

testimony in the U.S.

modelling groups on the results of their model predictions. 7

Representatives

of various modelling groups considered in this work have all testified before

U.S.

GCM's

in

determining

greenhouse

three

major

Research (NCAR),

NASA

Goddard

dimensional

climate

will

focus

on GCM's

Institute

of

data

Space

for

was

Modelling

in

In particular, we will analyse data from

the

National

Center

for Atmospheric

the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (GFDL),

models,

intercomparison.

models

we

predictions,

assessing the credibility of theory.

the

Because of the central role of

Congress on greenhouse change predictons.

Studies

available

made

groups

(GISS).

at

the

in

United

8

a

and the

For these fully three

form

Kingdom

that

facilitated

Meteorological

6

Note that the raw output of an individual 3-D climate model is generally not considered to be a hard

forecast or prediction. Rather, the output is the result of a sensitivity study, say to doubling of carbon

dioxide in the atmosphere. Results of sensitivity studies effectively become predictions or projections

when people start to have confidence in certain aspects of the results. Confidence may come through

consistency with theoretical principles or observations, or confirmation through other sources (other

3-D models or simpler models). This is typical of the way that science works, and should not be

The forecast does not consist of every tiny detail yielded by the model

considered unusual.

experiment, but usually just of the broader scale features, or those features that seem to be grounded

In a weather forecast model, the

on plausible physical mechanisms, or appear- as an overall trend.

patterns yielded on a particular day are intended to be predictions for that day. Climate however, is

really only meaningful in an average sense, and model patterns for individual years are not intended to

be forecasts for those particular years.

7

Readers may well be familiar with the recent testimony of Hansen (1989) (Director of the NASA GISS

climate group) which received media attention (New York Times, 1989d) after being altered on fairly

blatant ideological grounds by the Office of Management and Budget.

8

Running a 3-D climate model requires large resources in financial, technological, and intellectual

capital, and there are currently few 3-D climate models worldwide. The best known climate modelling

groups are listed here. To aid the reader in identifying the groups in subsequent discussion, members

of the groups who are prominently featured as authors on most of the groups papers are listed as well:

NCAR (Washington), GFDL (Manabe), GISS (Hansen), UKMO (Mitchell), and OSU (Schlesinger). UKMO is

the United Kingdom Meteorological Office, and OSU is the Oregon State University.

1

Introduction

16

Office

and

(UKMO)

Oregon

University

State

greenhouse climate experiments,

also

performed

in

are not directly included

but their results

For UKMO, output from the CO 2 experiments was not available at

analysis here.

The OSU model has severly limited

the time thesis research was undertaken.

vertical

have

(OSU)

(2

resolution

levels)

is

and

therefore

well

not

suited

for direct

comparison with the other 3-D models.

and

intents

purposes just

impossible to verify

as

complex

real

system. 9

climatic

to verify

(however, attempts

we

manageable,

To keep this

the

to

simulation

process

a single

to

validate,

has

and until now

of climate,

major models.

for the three

scrutinized

consider

albeit

a

We have chosen to validate the energy transport because it

fundamental one.

is fundamental

will

isolated

even

aspects of model performance have not been extensive to date).

study

It is

all aspects of GCM performance in simulating the earth's

it might change

climate and how

the

as

are for all

since the GCM's

Further refinement of scope is necessary,

The

from

results

not been

a validation

of

energy transports do not yield definitive answers to questions of credibility of

the models, but constitute an important case study from which to explore this

issue.

The role of energy transport can be understood in terms of the earth's

annual

radiative

energy

The

budget.

earth

receives

significantly

more

solar (short wave) energy in the tropics than in the polar

annually

averaged

regions.

The emitted longwave energy is more uniform over the globe, and is

unable to completely offset the equator to pole gradient in the solar heating,

resulting in

a strong

equator to pole net heating

the fundamental

heating

gradient

is

oceanic

general

circulation

energy

transport.

radiative

Since

and dynamical

deficiencies are occuring.

driving

(Ramanathan,

the

energy

processes,

force

1988),

transport

analysis

This

gradient.

for

and

the atmospheric

results

reflects

radiative

the

a

poleward

action

of both

in

of it may indicate

We will also use a one-dimensional

and

where model

energy balance

climate model to study how sensitive the climate is to the energy transport.

9

0f course, the GCM's are gross simplifications of the real climatic system, but they capture many of

the essential processes and feedbacks, and possibly even some of the intrinsic internal behaviour. As

While we

such, they are far too complex and sophisticated for us to fathom all their interconnections.

can perform sensitivity experiments with GCM's, and examine important processes in isolation with

simpler models, the GCM's remain black boxes to some degree.

1

Introduction

17

the

earth,

which

temperature

energy

in

turn

gradient,

transport

which

is thus

not modelled

through

climate.

component

an important

the

ice-albedo

the meridional

Validation

in the overall

of the

verification

greenhouse change projections.

role in

a fundamental

If the transports play

are

climate

regional

influences

of GCMs used for developing

yet

the

influences

The energy transport also determines

mechanism.10

feedback

iceline position on

an important role in determining the

The transport plays

as

well

we

suspect,

are

what

the climate,

determining

the

implications

for

We will consider this

credibility of the models and greenhouse predictions?

and outline the process by which credibility is generally established.

question,

There are no sufficient tests that can be performed to validate the models, so

that confidence

theory

and

is established

this point is crucial for the policy

Understanding

observations.

a gestalt of

by considering

in the predictions

analysis of greenhouse theory if any sense is to be made of it at all by the nonthe

Otherwise,

climatologist.

debate

validation

greenhouse

degenerate

can

into a series of apparent refutations and confirmations.

The

task

second

address

is to

of greenhouse

knowledge on validation

the

of translating

problem

domain to

the scientific

theory from

available

the public domain, in so far as this is relevant to the formulation of policy

responses

many

to greenhouse

levels.

testimony

channels

reaching

press,

radio,

This translation

is between

of communication

television

interviews,

magazines.

All

and

and

occurs

through

One of the more

to politicians.

of scientists

goes on at

of knowledge

most direct forms of translation

of the

One

Congressional

change.

and the media in

scientists

through

popular

fora

articles

have

in

various

newspapers

and

shortcomings,

and the lack of available time and space is common to all of

those listed above.

greenhouse

theory

literature.

Keeping

communication

far

By far the most sophisticated

(and

with

also

the

our focus

root

on

source)

source of information on

is

fundamentals,

the

we

scientific

have

journal

chosen

to

10

Ice-albedo feedback begins when an initial warming causes sea ice and snow to melt. This shrinking

Incrementally more

of the snow and sea ice margins results in a lower albedo in these regions.

incoming radiation can then be absorbed in the formerly ice- and snow-covered areas, thereby

resulting in further warming, more snow and ice melt, and so on until equilibrium is established. For

cooling, the reverse occurs.

Ice grows and increases the albedo and energy loss, leading to further

cooling and growth of ice.

1

Introduction

18

analyse

this

medium

for

the

translation

of

greenhouse

theory

(and

the

problems of validating theory) to the policy level.

The

interpreted

coverage

in

disseminating

also

interpretation

shapes

the

of the journal

that media interpretation

linking science

with

knowledge

receipt

articles

of the

policy

theory

and

and

the

theory

knowledge

determining

controversies

publicly.

of

theory

presentation.

greenhouse journal

and in

been

has

Press coverage of journals is

and resultant

the credibility of greenhouse

greenhouse

of

of

theory

greenhouse

in the press throughout its history.

instrumental

assesses

on

literature

journal

science

literature

Press

through

We believe

is important in

how the policy

community

theory.

Thus,

we

will consider

relating

to

are

presented

in

the

are then

interpreted

by

the

journal

literature,

media.

The New York Times will be used as the principle media source, because

it is well archived

discussion

research

of

results

articles

and is among the most sophisticated of the presses in its

environmental

relevant

various patterns

attempt

how the journal

it

how

to classify

them

context contributes

to

Misinterpretation

validating

to

and types

issues.

greenhouse

of misinterpretation

the occurence

theory

can

media

the

is

frequent,

be identified.

the failure

and show how

in

to

We

provide

and

will

appropriate

Though

of misinterpretation.

of

instances

of misinterpretation of the validation of theory probably result from errors by

the media as well as scientists, we primarily will be concerned with the role of

scientists.

above, it is hoped that we

Through the sequence of analyses described

can identify what the major problems associated with validation of greenhouse

theory

are,

and

the

how

problems

are

being

dealt

community in presentation to the policy community.

have

policy

scientists

think

framework

about

when

the

validation

communicating

attempt at this last problem would try to account

the

by

science

A longer range goal is to

problem

validation

with

in

relationship

to

the

Any serious

information.

for the factors motivating

scientists in framing their results, which is too big a task for this thesis.

In subsequent

the role of climate

climate models.

chapters

we will briefly outline

greenhouse

theory and

models, before reviewing previous work on validation of

We will then describe

the three climate models

considered

1

Introduction

19

here, the output used

from the models,

and the observational

data used

to

The results for validation of the models will be

with the models.

Implications of errors

presented, and implications of the results considered.

in the energy transport on climate sensitivity will be examined by

compare

Taking

parameterizing 1-D energy balance models with output from the GCMs.

the validation issue in a wider context, chapter eight will present a scienceThe penultimate chapter will consider how well

policy validation framework.

greenhouse theory is presented,

and conclusions will follow.

1

Introduction

20

2 GREENHOUSE THEORY

2.1

Greenhouse

Perhaps

way

good

been discussed

has

to

in the

widely

through

a

We note that greenhouse

scientific

without close attention to language definition.

is

theory

greenhouse

introduce

definition of parts of the theory.

and

breakdown

theory

a

effect

literature

the press

and

This has resulted in a blurring

of distinction between key parts of the theory.

Following

'greenhouse

effect'

physics

(primarily

radiatively

whereby

at the earth's

than

the

change'

to

we

will

to

refer

use

absorption

gases

warm surface of the earth.

in the infrared

dioxide and ozone)

different

blackbody

absorb

by

of

temperature

the longwave

radiative

anthropogenic

gases

a

and clouds, maintains

of

the

considerably

radiation

The

planet. 11

emitted

by

the

This energy is reemitted back to the surface, and

This yields a

also back into space at much colder atmospheric temperatures.

nothing

parts

various trace

in the lower troposphere

surface and

equivalent

active trace

net trapping of

terms

the

The greenhouse effect refers to the well known and basic

water vapour, carbon

temperature

greater

'greenhouse

and

greenhouse theory.

radiative

communication)

(personal

Handel

energy

or greenhouse

in this definition,

effect.

is

there

Note that

time dependent.

nor even anything

The above description of the greenhouse effect can be set in quantitive

The effective radiating temperature of the earth,

terms quite easily as follows:

Te, is determined by the requirement that infrared emission from the planet

balance the absorbed

solar radiation thus:

47cR 2aTe = nR 2(1-A)q,

where R is the radius of the earth, a

(2.1)

the

constant,

Stefan-Boltzmann

A

the

albedo of the earth, and qo the flux of solar radiation at the mean earth-sun

distance.

Choosing realistic values of A=0.3

and qo=1367W/m

2

(following

11The references to earth and its primary greenhouse gases could easily be removed to allow the

definition of greenhouse effect to apply to other planets as well.

2

Greenhouse theory

21

The mean surface temperature of the earth

Hansen et al. 1981) yields Te=255K.

The 33K difference between this and the blackbody value of

Greenhouse

255K is due to the greenhouse effect of trace gases and clouds.

gases cause the infrared opacity of the atmosphere to increase, and the mean

To achieve radiative balance, the

radiating level to be above the surface.

is about 288K.

temperature of the surface and atmosphere must increase until the emission of

1

radiation from the planet again equals the absorbed solar radiation. 2

Jean-Baptiste

mathematician

The

the

described

Fourier

greenhouse

Fourier essentially understood that the earth's

atmosphere is largely transparent to solar radiation, while it retains some of

Early investigations of this

the longwave radiation emitted from the surface.

basic greenhouse effect were concerned with explaining why the temperature

effect in 1827 (Fourier, 1827).

at the surface of the earth is as warm as it is.

the greenhouse

effect

is

as

as

important

Ramanathan (1988)

in

solar energy

notes that

maintaining

the

temperature of the planet.

change

Greenhouse

2.2

'Greenhouse

change'

refers

an

to

alteration

of the greenhouse

effect

to the time dependant build up of greenhouse gases (carbon dioxide,

chlorofluorocarbons, methane, etc.) in the atmosphere, that perturbs the

related

climatic

the

system

terms

from

greenhouse

greenhouse

climatoligical

effect

is

global

effect

well

field, whereas

radiative

and

equilibrium. 1 3

greenhouse

understood

and

greenhouse change

change

widely

The distinction between

is

since

the

in

the

understood,

and

useful,

acknowledged

is less well

1

still disputed in various details within the climate community. 4

Hansen et al. (1981) describe a useful analogy to the surface temperature resulting from the

greenhouse effect in terms of the depth of water in a leaky bucket with constant inflow rate. If the

holes in the bucket are reduced slightly in size (increased concentration of greenhouse gases), the

water depth (infrared opacity) and water pressure (tropospheric temperature) will increase until the

flow rate out of the holes (the radiation leaving the planet) again equals the inflow rate (the radiation

entering the planet).

13

Greenhouse change could be defined more broadly to refer to changes in trace gas concentrations on

paleoclimatological time scales, leading to warming or cooling. In this paper it will be used mostly in

the sense of recent changes (plus and minus one hundred years or so from the present), and so refers to

the largely anthropogenically induced greenhouse change.

14

1t does not enhance the policy debate to lump the greenhouse effect in with greenhouse change,

thereby attributing unnecessary uncertainty to a part of theory that has been widely accepted.

12

2

Greenhouse theory

22

(unpublished)

Tyndall

15

Chamberlin

and

(1896)

and later Arrhenius

were the first to apply the notion of greenhouse change by considering

In particular, they

changes in atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration.

(1897)

were

carbon

invoking

dioxide

for understanding

mechanisms

The

variations

dioxide

in carbon

changes

epochs.

glacial

past

to

related

past

in how

interested

is

climate

greenhouse

now

theory

variations

of the

the

of

were

change

of climate

one

as

viewed

concentration

major

(Ramanathan,

past

1988).

With the

work

of Arrhenius

greenhouse

(1908)

began

change

to be

viewed as a possible consequence of human activity as well as being related to

George Callendar circa 1940 was the first to

longer term natural variations.

Callendar

suggest that human activity had already led to greenhouse change.

effectively

synthesized

emissions,

atmospheric

information

on

CO 2

CO 2 's radiative characteristics, and

fossil

CO 2 concentration,

consumption

fuel

and

He combined

marine and land surface temperatures between 1880 and 1935.

these observations with simplified models of air-sea exchange of CO 2 and

surface

radiation

energy

balance

climate

models

to

a

develop

theory

of

greenhouse change, the essence of which is yet to be disproved (Ramanathan,

The theory contends that increased atmospheric CO 2 concentration can

1988).

be attributed to CO 2 released by fossil fuel combustion, since the exchange of

C 02 between the air and the intermediate ocean waters is not fast enough to

absorb the excess CO 2 from industrial activities. Further, CO 2 strongly absorbs

radiation in the 12-17pm region, and hence the increased CO 2 would radiatively

heat the surface.

The increased CO 2 heating is then invoked by Callendar to

help explain the observed global warming. 16

Subsequently,

short term global surface air temperature

1970) levelled off somewhat, and probably

changes

(1940-

a decline in

helped contribute to

attention to Callendar's

theory.

Following the work of Plass, Revelle, Suess,

the

1950's,

greenhouse

and

Keeling

in

theory

underwent

refinement with the paper by Manabe and Wetherald (1967).

a

significant

They utilized a 1-

15

The reference to Tyndall's involvement here is speculative (Handel, personal communication).

It is interesting to note that Callendar is not distressed by the possibility of warming, since like

Arrhenius (1908), he views the warming as protection against pending ice ages.

16

2

Greenhouse theory

23

D

model to demonstrate

radiative-convective

strongly

are so

coupled by

forcing

greenhouse

relevant

convective

heat and

moisture

the

surface

governs

that

and troposphere

that the surface

transport that the

warming

radiative perturbation of the troposphere as well as that of the surface.

D radiative-convective models opened the way for the development

the

is

The 1of 3-D

climate models, and still form an important tool for interpreting the 3-D model

results.

For a comprehensive

of

description

greenhouse

theory,

the reader

is

We shall proceed with a basic

referred to Ramanathan et al. (1987).

description of a 3-D climate model, and model CO 2 equilibrium experiments.

The particular NCAR, GFDL, and GISS climate models will be described in the

chapter on models.

2.3

will

Climate

models

and

climate

Before discussing the role of climate models in greenhouse theory, we

briefly outline the approach taken in constructing a 3-D model of the

According to the traditional approach (outlined in Schneider

and Dickinson, 1974), a climate model attempts to account for the basic factors

governing climate (solar radiation, ocean circulation, ice cover, vegetation,

winds, etc.) by relating them by the equations expressing conservation of

climate system.

mass,

momentum,

and

energy,

together

with

the

thermodynamical

and

chemical laws governing the change in material composition of the land, sea,

The set of coupled non-linear three-dimensional partial differential

and air.

equations yielded by the theory are solved subject to the external input of

solar radiation,

and for a given initial

state of the earth-atmosphere

system.

In principle, the time dependency of the equations allows for modelling of the

evolution of the dynamical and thermodynamical state of the atmosphere, land

The equations are solved on a three-dimensional grid representing

and ocean.

Some models use a combined grid and spectral

Typical GCM

computational efficiency and accuracy.

latitude, longitude, and height.

representation

for

resolutions are at best a few degrees of latitude and longitude horizontally, and

Processes occuring on scales larger then

a few kilometres or so vertically.

these

are

explicitly

treated,

whereas

phenomena

occuring

on smaller

2

scales

Greenhouse theory

24

such

as

cumulus

convection,

condensation,

transport,

and

cloud

be parameterized. 17

formation must

The task of modelling climate

enormous

turbulent

number of operations.

on a computer involves performing

Following

Stone

an

communication),

(personal

consider solving for say 10 primary variables over a 3-D grid of 100 latitude

points x 100 longitude points x 10 vertical levels.

This yields 106 unknowns at

For 15 minute time steps over a typical simulation period of say

each time step.

Large computers

30 years, the number of unknowns to solve for is about 1012.

are required for such an undertaking.

Schneider

appropriate

and Dickinson

spatial

for

technique

parameterization

and

resolution

"the technique

note that

(1974)

representation,

use

in

the

time

step

of these elements,

along

factors, determines the model."

with

the choice

The use of 3-D

models is a relatively new

2.4

(1975)

among the

For a good description of a single 3-D climate model, Hansen

in further details.

experiments

chemical

a good overview of climate modelling for those interested

Dickinson provides

(1983)

and

of physical

The article by Schneider and

first of the 3-D model papers in the literature.

al.

and

and the particular

addition to greenhouse science, with Manabe and Wetherald

et

size,

approximate

of

construction

theories of climate is a large part of the art of 'modeling',

choice

of selecting

is

comprehensive

and

includes

description

of

sensitivity

as well.

Greenhouse

change

modelling

experiments

To model the response of the climate system to greenhouse forcing, the

amount of CO 2 and other trace gases is simply increased in the radiation

scheme

of the model.

atmosphere,

which

in

This

turn

reduces the amount of energy

alters

the temperature

and then

leaving the

other climate

variables in the model such as winds, cloud cover, and precipitation patterns.

All that modellers require to generate the response of the system to an initial

perturbation

is

fundamental

equations,

17Parameterization

the

ability

to

in this

calculate

the

case absorption

physical

forcing

of radiation

terms

by gases

in

the

in the

is short for parametric representation.

2

Greenhouse theory

25

for conservation

equation

performed

a transient

as

energy

infancy however.

a transient

(Rind

experiment,

system to the forcing.

the climate

et al.

demonstrating

Transient

Ideally,

1988).

the gradual

are

experiments

this

is

response

of

still in their

represents the first published results of

Hansen et al. (1988)

experiment.

of

consistency

For

selected

of

from

results

across

comparison

the more traditional

modelling

we

groups,

equilibrium

GCM CO 2

have

response

In the equilibrium CO 2 response experiments, the model

experiments to study.

is first run for a number of years (typically 10 or 20 years of model time) with

The last ten years

boundary conditions and forcing factors as they are today.

or so of this control run provides an important test of how well the climate

model

simulates the

response

experiment

real climate

is to introduce

conditions or forcing factors.

doubling

instantaneous

The next step in the equilibrium

system.

a perturbation

In the experiments

carbon

of atmospheric

of the boundary

of one

considered here, this is an

dioxide

concentration.

18

Note

simulation of current climate in the control run is important for

experiment, since the doubling of CO 2 induces a perturbation on the

that accurate

the

If the current climate is not correct, then the accuracy of the

current climate.

perturbed climate

linearities

are

simulation may be called

important

and

cannot

into question in so far as non-

be linearized

with

sufficient

Because of the importance of the control run in the CO 2 sensitivity

accuracy.

experiment,

later analysis of transports in the major 3-D models will be for results from the

control

run

After

simulations.

instantaneously

doubling

number of years for the perturbed run.

CO 2 , the model is again run for a

The difference between the perturbed

run and the control run is a measure of the sensitivity of the model to the

The commonly quoted

prescribed change between two equilibrium conditions.

2 to 5K temperature change for a doubling of CO 2 in the atmosphere is based on

the results of these equilibrium experiments with GCM's. 1 9

18

The change of carbon dioxide in the models is usually taken as a surrogate for a change in all of the

greenhouse gases (Kellogg and Zhao, 1988).

19

The global surface air temperature changes resulting from these experiments for the models

considered in this work are: NCAR:3.5K; GFDL:4.OK; and GISS:4.2K, (and for UKMO:5.2K).

2

Greenhouse theory

26

of

doubling

CO 2

of

use

make

frequently

change

the

advocating

Arguments

for

the

GCM

predictions

temperature

Current

in the atmosphere.

greenhouse

to

responses

policy

need

GCM predictions

for

a

are rather

The greenhouse

sobering, and are quoted to stress the gravity of the problem.

policy arguments usually note that if the temperature response is as predicted

by the GCM's,

change will be virtually without

then the rate of temperature

precedent, and may have major implications for ecosystems and social systems.

We note then, that some arguments for greenhouse policy responses are

on the results of GCM model simulations, and so

predicated to some degree

investigation of the credibility of the models is a policy-relevant pursuit.

2.5

change

Greenhouse

controversies

From a policy perspective, a lack of consensus in a scientific community

on a particular theory weakens

seriously,

and

of scientific

part

are

disputes

Since

implemented.

policies

will be taken

the likelihood that the theory

development and will always exist to some degree, policymakers must ascertain

whether existing disputes are significant or relevant to the range of possible

policy options or not.

With this in mind, we turn to a discussion of greenhouse

disputes.

theory

In

greenhouse

theory,

the

effect

greenhouse

undisputed.

is virtually

With respect to greenhouse change, the important parts of the theory are the

determination of the greenhouse forcing, and the climatic response to the

forcing.

trace gas concentration

about.

of the radiative forcings associated with changes in

The magnitudes

However,

are reasonably

greenhouse

change

well understood,

is disputed

and not much argued

as to whether the climatic

change resulting from the greenhouse forcing will be as large as the models

predict, and as to whether the change is yet detectable.

Criticizm

crudity

of the

(ocean response,

models

in

neglecting

or

results

from

some simple models.

conflicting results, the work of Idso (1980)

surface

various

oversimplifying

clouds and moist dynamics, vegetation, hydrology,

ocassionally on conflicting

using

is based on the

of the magnitude of the model predictions

energy

balance

and Newell

considerations

stands

processes

etc.),

In regard

and

to

and Dopplick (1979)

out.

2

These

works

Greenhouse theory

27

less temperature

an order of magnitude

predicted

doubling

response to CO 2

These results have been explained by Ramanathan (1981) on

than the GCM's.

the basis that the "important tropospheric CO 2 radiative heating is ignored by

both Newell and Dopplick (1979) and Idso (1980)."

Probably the most potent criticizms related to global scale shortcomings

in the GCM's involve the representation of clouds and the role of cloud

For the current climate, Ramanathan et al. (1989) find that clouds

feedbacks.

play a major role in determining the radiative balance of the atmosphere, and

That is, clouds presently cool the

presently constitute a negative feedback.

than

they

radiation).

it

heat

The

question

reflecting

greenhouse

their

(through

crucial

in

effect

albedo

their

(through

planet

regarding

radiation)

shortwave

change

greenhouse

longwave

trapping

in

effect

more

is how

the

For the current

cloud mix would change in response to greenhouse forcing.

GCM's employing predictive cloud schemes, cloud changes provide a

significant positive feedback.

small increase

For the GISS model this occurs as a result of a

greenhouse

(enhancing cloud

in mean cloud height

effects) 2 0 ,

and a small decrease in cloud cover (decreasing their albedo effect) (Hansen et

Since current cloud schemes in the models are quite crude and cloud

al. 1984).

contain

significant uncertainty.

the predictions,

to

significantly

contribute

feedbacks

Uncertainty

alone

the

model

predictions

implies nothing

about

the

direction of potential error in the feedback, though there are some indications

in this regard, which we will consider.

feedback can occur as a result of changes in cloud

The 3-D models consider (albeit crudely)

and height.

Changes in cloud

composition, coverage,

As mentioned, the

changes in cloud coverage and height, but not composition.

changes in coverage and height in. the models are such as to lead to positive

As regards cloud composition, it is thought that the greater

feedback.

availability

of

water

vapour

for

condensation

in

a

greenhouse

warmed

atmosphere could lead to a systematic increase in cloud liquid water contents,

though the relevant physics are not well understood (Somerville and Remer,

1984).

In the 1-D

radiative-convective

model of Somerville

and Remer, the

20

As cloud top height is increased, the cloud top temperature becomes progressively lower than the

surface temperature, reducing the emission of longwave radiation from cloud top to space, and thus

enhancing the radiative heating of the troposphere and surface.

2

Greenhouse theory

28

of increased

cirrus)

is to increase

Mitchell

(1988)

In the

there

Remer,

temperature

of climate

is

limited observational

liquid

water

Somerville

content

with

above 273K.

et al.

by Twomey

mechanism was proposed

Another negative feedback

Twomey pointed out that an increase in tropospheric

(1984).

two.

and Remer may

data employed by

cloud

in

change

little

factor of

a

by

sensitivity

water content depends on factors other

correct, cloud liquid

than temperature.

and

decrease

notes that although the results of Somerville

be qualitatively

than thin

of clouds more than the greenhouse

the albedo effect

possible

and

other

(for clouds

This yields a negative feedback for cloud optical thickness

effect of clouds.

changes,

liquid water content

cloud

result

particulates will

lead to an increase in the number density of cloud condensation nuclei, which

A variant of this feedback involving

can enhance cloud optical depth.

biogenic processes was proposed by Charlson et al. (1987).

Over the oceans, the

number density of cloud condensation nuclei is influenced by the emission of

An increase in surface temperature

dimethyl sulfide from marine organisms.

could lead to an increase

in dimethyl

processes

are

certainly

plausible,

and thus also to an

notes that while the above

Ramanathan (1988)

increase in cloud optical depth.

microphysical

sulfide emissions,

the

of these

extent

global

demonstrated.

processes has not yet been satisfactorily

Some of the cloud physics not included in the model cloud schemes could

provide significant additional positive feedback also (Ramanathan and Handel,

communication).

personal

extent

and

longer

For instance,

allowed

lived than

vertical

heat

cirrus clouds may be of larger areal

for

transport

which

in the models,

than

the

microphysics

are

more

of

cloud

concerned

with

formation.

Cirrus shields would probably provide an additional positive cloud

feedback due to the dominance of their greenhouse effect.

In a

(1979)

1979 assessment

allowed

of cloud

a +1 0 C error in CO 2

uncertainties in high cloud effects.

temperature,

feedback effects on

doubling

response

temperature

NRC

due

to

Writing prior to such work as Somerville

and Remer (1984) and Twomey et al. (1984) they were unable to find evidence

for an appreciable negative feedback due to changes in low and middle cloud

2

Greenhouse theory

29

0

albedos or other causes, and allowed only 0.5 C as an additional margin for

2

error on the low side due to cloud feedback uncertainty. 1

The point of this discussion of cloud feedbacks is to illuminate the

controversy and complexity, and to recognize that criticizm of the magnitude

of the warmings produced by the models is not unfounded, but doesn't

necessarily

invalidate

the predictions

either.

Other areas in which GCM's are criticized is over the representation of

oceans, ond over the validity of equilibrium response as opposed to transient

Schneider and Thompson (1981) attemped to weigh the

seriousness of deliberately neglecting heat capacity of the deep oceans in most

models and of using a fixed-CO 2 increase instead of a time evolving scenario of

C 02 increase. The actual mixed layer of the oceans is generally deeper in high

response experiments.

latitudes than in low latitudes, and would therefore tend to heat up more slowly

Thus, although albedo/temperature processes would cause

in high latitudes.

high latitudes to warm more in equilibrium, mid-latitudes and some high

latitude

regions

would

not necessarily

warm up

as

fast as

lower latitudes

Just how important

during the transition period towards the new equilibrium.

actually

this process is depends on how rapidly the CO 2 concentration

If CO 2 increases rapidly, neglecting the transient would

increases with time.

be a more serious error than if CO 2

Schneider (1984)

increases

notes that atmospheric

more

addition,

In

slowly.

with

water vapour increases

surface

temperature increase, accounting for perhaps 25 to 40% of the equilibrium

During the transient warming

surface temperature response to CO 2 increase.

period, oceanic response may well lag that of the atmosphere, thereby

temporarily

reducing

occur after equilibrium

the

water

vapour

increment

that

would

eventually

was reached.

The transient warming response would also be affected by the rates at

which water from the ocean mixed layer mixes with water below it, and by

changes in the rate in response to climatic change. In the Hansen et al. (1988)

transient response experiment, the uptake of heat perturbations by the ocean

Bryan and

beneath the mixed layer is approximated as vertical diffusion.

21

0

Their overall estimate considering all sources of uncertainty was 3*C±1.5 C.

2

Greenhouse theory

30

(1985)

model.

During the greenhouse warming episode, their model yields a partial

collapse

of the

up

twice

investigate

thermohaline

ocean

much

as

as

heat

conclude

that

"an enhanced

feedback

for

greenhouse

circulation

thermohaline

circulation 2 2 , allowing the ocean to take

predicted

be

would

found in the numerical

simple

diffusive

and

Spelman

Bryan

the

However,

a

would produce

of heat

sequestering

warming.

by

conditions.

climatic

normal

under

approximation

CO 2 perturbations