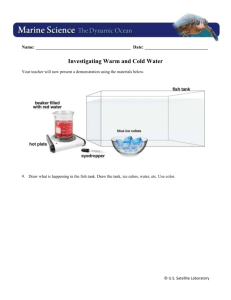

Transformative Copy

advertisement