The Indo-European Subjunctive and questions ... chronology

advertisement

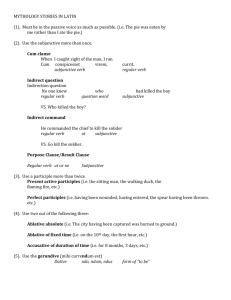

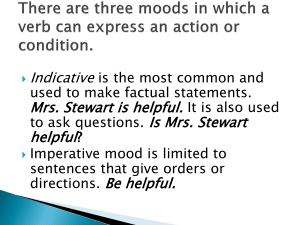

The Indo-European Subjunctive and questions of relative chronology Eystein Dahl, University of Oslo 0. Although the Indo-European languages to a large degree are typologically similar, the wellknown differences in the verbal systems of the individual languages present serious difficulties for the reconstruction of the proto-language. In the present paper I will discuss some of the grams found in the earliest attested IE languages which are used with future time reference and how these forms may be related. 1. It is a widely accepted fact that the semantic notion of futurity is not purely temporal. In many languages the forms used for expressing future time reference may also express supposition, intention, desire and other modal meanings. Bybee et al. (1994) observed that there is a significant cross-linguistic tendency that languages may have more than one form expressing future time. In their view, this may be a consequence of the independent development of individual grams having different sources or from the same sources at different periods. The possible sources for grams having future time reference are manifold and, as pointed out by Bybee and her colleagues, there is a considerable potential for grams having future meaning to develop differences in their range of use. Considering that a substantial lapse of time must be assumed between the latest phase of PIE and the earliest surviving sources, it is therefore not surprising that the individual IE languages differ considerably as to what gram types may be used to express future time. At least five different formations exist in the daughter languages having future as one of their uses, cf. point 1. Handout. 2. The thematic subjunctive has two stem allomorphs, the short vowel subjunctive, of the type 3.sg.act. *h1éset(i), cf. ved. ásat(i), gr. , lat. erit. and the long-vowel-subjunctive of type *bhér t(i), ved. bhár t(i), gr. , lat. leget. Although the two mentioned stem allomorphs seem to have been complementary distributed in PIE, as the short-vowel forms were formed from athematic tense stems and the long-vowel forms originally were formed from thematic stems only, there is a marked tendency in Indo-Iranian and Greek to substitute 1 the long-vowel subjunctive for the short-vowel subjunctive, so that the short-vowel subjunctive is completely residual in Classical Greek. The thematic subjunctive is especially productive in Indo-Iranian and Greek, where subjunctive forms belonging to practically every stem of the verbal system are found. However, in both these languages the subjunctive occurs beside a more specialized future tense stem and, apart from some sporadic subjunctive forms of this stem in Vedic, the combination of the subjunctive and the future markers does not occur at all. This is probably a consequence of a close semantic relationship in the synchronic verb systems. The PIE thematic subjunctive may therefore be assumed to have had future time reference as one of its main uses, cf. point 2, Handout: The short-vowel subjunctive of athematic root stems seems to have been structurally parallel with the baritone thematic root presents, (punkt 3, handout). Both these stem types have egrade throughout the paradigm. However, it must be admitted that some of the subjunctive forms found in Indo-Iranian to some degree seem to reflect another morphological pattern, as they do not show the expected stem form (cf. punkt 4, handout). Because of the parallel morphological structure of these two categories, the thematic subjunctive has often been regarded as secondarily developed from the baritone presents, cf. e.g. Meier-Brügger 2002. Still, it has been recently argued by Tichy that the metrical value of the long-vowel subjunctive forms in Gathic Avestan points at a distinctive subjunctive suffix *-h1é-, cf. point 5, handout. If this analysis is correct, it would seem that the subjunctive had a very ancient origin indeed. However, the fact that the attestation of the thematic subjunctive in the daughter languages is rather limited speaks in disfavour of such a view. Furthermore, the evidence of Gathic Avestan is in my opinion a rather meagre basis for postulating a distinct suffix in PIE, although it must be acknowledged that the bisyllabic reading of the stem type in question is remarkably consistent in these texts. One could easily imagine that such a metrical value were due to a secondary reanalysis of the long-vowel forms in this language. Therefore, it is in my view more parsimonious to regard the thematic subjunctive as a secondary category, having developed out of the thematic present stems. According to Tichy, the semantic derivation of the thematic subjunctive from the present indicative is unconvincing. However, such a derivation is corroborated by broad crosslinguistic evidence. In a tense system not having any distinct gram for expressing the future, a form primarily being associated with an imperfective present meaning in many cases can be used with future time reference, particularly when the verbal predicates denote a telic event. This difference between a telic and an atelic reading of present forms even in a language 2 having several means of expressing future time reference may be illustrated by the two Vedic passages found under point 6 in your handout. It is a common assumption that at least some of the ancient IE languages have developed from a common proto-stage where a grammaticalized opposition between imperfective and perfective aspect expressed through different stems of the same verb was central. Hoffmann and Rix have developed a two-stage diachronic model, where this stage is preceded by a stage where lexically determined and derivationally expressed aktionsarten were the primary means of expressing aspectual meanings. The curious fact that PIE seems to have known a rather broad range of competing stem formants, especially in the present system, is easily explained by the hypothesis of Hoffmann and Rix. The stem formants originally were markers of different aktionsarten, which in the new binary aspectual system were reinterpreted as markers of imperfective or perfective aspect. As is well-known, the simple root may occur as a marker of either aspect, something which is probably due to the basic lexical meaning of each verb. However, in the PIE stage of the binary aspectual system there are two stem types which may be regarded as prototypical aspectual stems, namely the imperfective baritone thematic present and the perfective sigmatic aorist. The former is in our context the most interesting, as we have noted that it is structurally parallel to the subjunctive of certain stem types. In his comprehensive monograph on the Vedic first class presents, Got concluded that the primary function of the PIE baritone presents was to furnish inherently telic verbs with a form explicitly expressing the ongoing character of the action. If this analysis is correct, a possible semantic link between the thematic subjunctive and the baritone present arises. An explicitly imperfective form of a telic verb in many cases could be used with future time reference, as previously mentioned. The excessive productivity of the baritone present stem type in several daughter languages may be taken as evidence for its productive character in PIE. In my opinion, this may to a large degree be interpreted as a consequence of the central status a form with neutral imperfective meaning would have in a binary system where imperfective aspect was one of the most central semantic features. Thus the productivity of the baritone present may be plausibly linked with the grammaticalization of the aspectual opposition. Another important consequence of this system change would be that the various present stem formations gradually lost their original semantic characteristics. In the various stages of this process, there would be the possibility that some verbs tended to be associated with a certain present stem formant because of suiting semantics or of type/token frequency or both. In such 3 cases, the second of the two scenarios for morphological renewal proposed by Kuryłowicz would apply, namely that the old morph, originally having a primary and a secondary function, maintained its primary function, being supplanted in its secondary function by a new (derivational) morph, cf. the scheme found under point 7 in your handout. A similar analysis was proposed by Renou (1932), who regarded forms like kárati, gámati etc. as having a semi-modal function in the synchronic system of Vedic, being partly interpretable as forms of the present indicative. Although this approach has been severely criticized by Hoffmann (1955), who argued that these forms were to be analysed as subjunctives of the root aorist, it seems to me that Renou was on a right track, after all. If the proposed analysis is correct, the PIE thematic subjunctive originally was formed directly from the root, as proposed i.a. by Szemerenyi (1990). One could easily imagine that the incipient subjunctive category spread from some verbs, where it was established as a specialised future, to other verbs, in the end being fully grammaticalized and thus generalized to every verb stem. I believe that an important factor in this process could be the increasing use of the subjunctive in subordinate clauses, as is the case in Ancient Greek. There is little comparative evidence for assuming that the present subjunctive actually had a range of uses distinct from the aorist subjunctive when used in main clauses. 3. The sigmatic formations found in various IE languages also deserve a brief treatment. It is evident that all the various sigmatic formations have the verbal root, rather than a stem as their derivational basis. The sigmatic forms seem to have an original agent-oriented intentional or desiderative meaning in common and thus may be regarded as fairly closely related. I cannot treat the relationship between these formations in any great detail, but I will present a rough outline. The so-called si-imperatives constitute a suitable starting-point for the discussion of the sformations. Such forms are primarily found in Vedic, but comparable forms are found in Hittite, Tocharian, Messapic and Old Irish. At first view, these forms are seemingly formed through a combination of the primary ending of the 2.sg.act. with the e-graded verbal root. These forms stand quite isolated in the synchronic verbal systems of the mentioned languages and thus may be regarded as quite archaic. However, in Vedic the si-imperative forms are closely associated with the independent sa-subjunctives of the type satsat, cf. Narten (1964), Cardona (1965). In a seminal article, Szemerenyi (1966) showed that the syntactic use and semantics of the forms in –si in Vedic was similar to that of other subjunctive forms rather than the imperative. To account for the irregular form of these forms, Szemerenyi suggested 4 that the subjunctive forms of the second person singular in Proto-Indo-Iranian (PII) underwent a process of haplology, so that a form like PII *dársasi would yield *dársi, ved. dár i. As may be inferred from the si-imperatives found in other languages, such a process cannot be exclusively Indo-Iranian, but must be assumed to be of a somewhat earlier date, as pointed out by Jasanoff (2003). Contrary to Jasanoffs view, I do not believe that the si-imperatives are sufficient to prove the prehistoric existence of a fully developed thematic subjunctive in the prehistory of Anatolian, for reasons which should already be clear. However, Rasmussen (1985) has convincingly demonstrated that the si-imperatives rather seem to have belonged to an athematic paradigm, reflected by some other residual Vedic and Old Irish forms (cf. Handout, point XXX). Furthermore, the 3.sg.future form of the type duõs may be taken to continue an athematic paradigm, although the status of this form remains somewhat contended. The Old Latin future of type fax , the subjunctive of which has the form faxim seems to continue an originally athematic stem, may also belong to this group of forms. The si-forms may be interpreted as remnants of this athematic formation, being partly included in new paradigms in the individual languages (cf. Vedic) and partly retained as paradigmatically isolated forms (cf. Hittite, Tocharian, Old Irish). The semantic development of the si-imperative seems to presuppose a stage where the desiderative-intentional meaning of the s-forms had developed a more distinctly future meaning, as imperative occurs relatively late on this kind of semantic path. If we on the basis of this evidence suppose that the original sigmatic paradigm was athematic, some further observations can be made. Firstly the *-se/o-formation reflected primarily by the sa-subjunctives found in Indo-Iranian occurring beside non-sigmatic aorist formations, which synchronically differ only slightly from the thematic subjunctive, and the Greek sigmatic future of type . Although there have been some attempts at deriving these formations from the thematic subjunctive forms belonging to the sigmatic aorist, several reasons remain for assuming another origin for these forms. First, as pointed out by Tichy (2004), there is no obvious reason why the subjunctive forms of the sigmatic aorist should have a more aptly characterized morphological structure than corresponding forms from other aorist stems. Second, neither the Indo-Iranian formation nor, more seriously, the Greek future shows any trace of a perfective meaning. Third, imperative forms and participles from these stems are attested both in Indo-Iranian and Greek, and fourth, in some cases the Indo-Iranian forms convey a desiderative-intentional meaning which is not semantically compatible with a development from the thematic subjunctive. It is an unquestionable fact that the thematic 5 subjunctive is primarily used for expressing an expectation of the speaker. In the crosslinguistic survey by Bybee and her colleagues, there are several examples of desiderative forms developing imperative and future uses, but examples of the contrary are rare or nonexisting. Although the possibility of a divergent path of semantic development cannot a priori be excluded, uncommon or unattested semantic developments should rather be avoided in reconstruction. As to the form of the *-se/o-formation, it probably reflects the general tendency found in several IE languages that thematic stems or single forms substituted athematic ones. This tendency seems to be old and is particularly found in the present system. The *-s é/ó-formation also seems transparently derivable from an athematic paradigm, through an affixation of the common present formant in é/ó-. Although both finite and infinite forms of this stem type are attested in Indo-Iranian and Baltic, Jasanoff (1975) argues that the finite forms seem to be secondary, because of the fact that the Vedic evidence shows a preference for forms of the participle. However, this preference is in my view rather to be explained as a consequence of the synchronic situation in Vedic, where several finite forms having future time reference concur, while the participle of the sya-stems, having an intentional or desiderative meaning, does not have any productive rivalling forms. Furthermore, the Gaulish future pissíiumi “I will see” corroborates the assumption that there has been a PIE s é/ó-formation from which both finite and infinite forms could be created. The reduplicated thematic s-stem is primarily attested in Indo-Iranian and Old Irish, but morphologically comparable isolated forms also occur in other languages (cf. Latin disc – ere “to learn” < *di-d -sé- “be willing to perceive”). The exact formal relationship of this formation to the other s-formations is not entirely perspicuous, but its desiderative-intentional meaning found in Indo-Iranian makes the assumption of a common origin tempting. The future meaning of the Old Irish forms may safely be regarded as secondarily developed from a desiderative meaning. 4. On the basis of the present discussion, we may draw the following conclusions: • The comparative evidence allows for postulating two genetically distinct means of expressing future time in PIE. One, the thematic subjunctive, seems to have developed out of the present indicative, the other, the sigmatic formation has a desiderative origin. 6 • The sigmatic formation seems to belong to a fairly remote stage of PIE, as the siimperatives which have been identified in Hittite may be interpreted as remnants of this formation. • The thematic subjunctive is relatively young, as it seems to presuppose at least an early stage of the development of the binary aspectual opposition found in late PIE. No evidence for the thematic subjunctive is found in Anatolian, something which is in perfect accordance with the lack of unequivocal evidence for the aspectual opposition in this language group. • Furthermore, the fact that Ancient Greek presents a seemingly more advanced syntactical use of the thematic subjunctive than Indo-Iranian may be of some significance for the chronological stratification of the IE languages. The Indo-European Subjunctive and questions of relative chronology (Handout): Eystein Dahl, University of Oslo (eystein.dahl@ikos.uio.no) August 6. 2005 1. PIE formations with future time reference: a) The thematic subjunctive h1éset(i) and ásat(i)/bhár t(i), gr. subj. / *bhér t(i), e.g. ved. subj. , lat. fut. erit/leget (cf. 2.sg. leg s), b) A thematic s-formation *sté set(i), e.g. ved. independent “sa-subjunctive” stó·at, gr. fut. . c) An athematic s-formation * é dsti, e.g. lat. v sere. d) A formation characterized by the suffix *-s é/ó- *deh3s éti, e.g. ved. fut. d syáti¸ lith. fut. 1.pl.act. dúosime, gaul. fut. 1.sg.act. pissíiumi. e) An reduplicated thematic s-formation *g hig h séti, e.g. ved. desiderative jigh µsati, oir. fut. ro:mmaid. 2. Thematic subjunctive with future time reference in Greek and Indo-Iranian: Hom. Il. I 262: ” for never did I see such men nor shall I ever see them” RV I 48.3: uv²sa u·² uch²c ca nú 7 ” Dawn has flushed (in the past) and she will flush now” 3. Indicative forms of baritone root stems and subjunctive forms of athematic root stems: a) baritone present stems ind. 3.sg.act. *bhére-ti, cf. ved. bhárati, gr. b) simple athematic root stem (amphidynamic stems) ind. 3.sg. act. *h1és-ti, cf. ved. ásti vs. subj. *h1ése-t(i), cf. ved. ásat(i), lat. erit c) ” Narten presents” ind. 3.sg. act. *stḗ -ti cf. ved. stáuti vs. subj. sté e-t(i), cf. ved. stavat. d) Sigmatic Aorist ind. 3.sg.act. *én Hs-t cf. ved. 1.sg.act. ánai·am vs. subj. *ne se-t(i), cf. ved. ne·ati. 4. Indo-Iranian (Vedic) subjunctive forms not conforming to this pattern: a) Subjunctive forms from athematic reduplicated present stems: 2. 3.sg.act. dadas, dadat (vs. ind. dád si, dád ti)etc. b) Subjunctive forms from athematic nasal presents: 3.sg.act. p¨öáti (vs. ind. p¨ö²ti). c) Subjunctive forms from intensive stems: 3.sg.act. dardirat (vs. ind. dardar ti) 5. Gathic Avestan long vowel subjunctive forms having bisyllabic reading cf. Monna (1978), Tichy (2002): e.g. paitiš t to be measured –a’at. 6. Future meaning of telic verb vs. non-future meaning of atelic verb in Vedic: RV IX 20.7b: pavítraµ soma gachasi (pr. ind. 2.sg.act.) : ” Soma, you are going into the strainingcloth” RV IX 96.23a: apaghnánn e·i (pr. ind. 2.sg.act) pavam na átr n : ” Pavam na (Soma), you are wandering about, destroying (your) enemies” 7. Phases in the development of the development of the thematic subjunctive: a) Telic verb: *g em- “ go to, come” 8 Root Aorist *g em-, cf. ved. aor. ind. ágan “ he came, has Old Present Stem *g cf. ved. pr. ind. gácchati “ he comes” come” s e- New Present Stem *g eme- cf. ved. aor. subj.: gámati “ he will come” b) Atelic verb: *h1e - “ to go, wander” (Old) Root Present *h1e - cf. ved. pr. ind. éti “ he is wandering” Subjunctive *h1e -e- cf. ved. pr. subj. áyati “ he will, is going to wander” c) Long-vowel subjunctive: *bher- “ to carry” Baritone thematic present *bhere- cf. ved. pr. ind. bhárati “ he carries” Subjunctive *bhere-e- cf. ved. pr. subj. bhár ti “ he will, is going to carry” d) Opposition between present and aorist subjunctive: *bh eh2- “ to grow, arise” Root aorist *bh eh2- cf. ved. aor. ind. ábh t “ he has grown, *bhe h2e- cf. ved. pr. ind. bhávati ” he is growing” arisen” . Baritone Present Aor. subj. h *b eh2e- cf. gath. av. subj. buuait “ he will grow, is going to grow” Pr. subj. *bhe h2e-e- cf. ved. pr. subj. bháv ti ” he will grow, is going to grow” 8. si-imperative beside sa-subjunctive in Vedic (Narten (1964), Cardona (1965), Szemerenyi (1966)): Ved. imperative 2.sg. satsi : subjunctive 3.sg. satsati, cf. aor. ind. ásadat [< *sed-t]. Szemerenyi: dar·i < IIR *darsasi, by haplology. 9 9. si-imperatives in Hittite, Tocharian, Old Irish, Messapic (cf. Rasmussen 1985, Jasanoff 2003): a) Hittite eši “ settle!” , ešši ” perform!” , pa ši ” protect!” . An inherited form *n ši may underlie the sigmatic imperative 2.sg.mid. naiš ut, neš ut “ turn!” . b) Tocharian A päklyo·, B päklyau· (: ved. ró·i) “ hear!” c) Old Irish tair “ come!” , no-m-ain “ spare me!” , tog “ choose!” , aic(c) “ invoke!” , at-ræ “ arise” etc. d) Messapic klaohi “ hear!” 10. Athematic s-paradigm (cf. Rasmussen 1985): Active 1.sg. *sté -s- Middle > ved. stó·am *stu-s-h2ái > ved. stu·é 2.sg. *sté -s-si > ved. stó·i *stu-s-só > ved. stu·é 3.sg. *h3ré -s-ti > oir. at-ré *stu-s-ó > ved. stu·é Perhaps also the 3.sg.act. of the Lithuanian future duõs, Old Latin future fax (the corresponding subjunctive (PIE optative faxim seems to belong to an originally athematic stem). 11. Desiderative origin of the s-formations: a) *-se/o-formation: Vedic nom. pl. mask. abhinák·anto (RV II 24.6) “ wanting to reach” , cf. Kümmel (2000), gr. imp. “we will take with us, will bring” , cf. Tichy (2004). b) *-s é/ó-formation (athematic –s+ é/ó-): ved. participle d syánt- “ wanting to give” . c) Reduplicated s-formation: jigh µsati “ He wants to kill” References: Bybee, J., Perkins, R. and Pagliuca, W. (1994): The Evolution of Grammar. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Cardona, G. (1965): „The Vedic Imperatives in –si“ , in Language 41, I, pp. 1-18. 10 Hoffmann, K. (1955) “ Vedisch gámati” in Münchener Studien zur Sprachwissenschaft 7, pp. 91f. (1970) “ Das Kategoriensystem des indogermanischen Verbums” in Münchener Studien zur Sprachwissenschaft 28, pp. 19-41. Jasanoff, J. (1975): “ The Baltic future” in Indo-European Studies II, Ed. Calvert Watkins. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University. (2003): Hittite and the Indo-European Verb. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Kümmel, M. J. (2000): Das Perfekt im Indoiranischen. Wiesbaden. Kuryłowicz, J. (1964): The Inflectional Categories of Indo-European. Heidelberg: Winter. Meier-Brügger, M. (2000): Indogermanische Sprachwissenschaft. Berlin-New York: De Gruyter. Monna, M.C. (1978): The Gathas of Zarathustra. A Reconstruction of the Text. Amsterdam: Rodopi. Narten, J. (1964): Die sigmatischen Aoriste im Veda. Wiesbaden: Reichert. Rasmussen, J. E. (1985): “ Der Prospektiv – eine verkannte indogermanische Verbalkategorie?” in Grammatische Kategorien Funktion und Geschichte, Ed. Bernfried Schlerath. Wiesbaden: Reichert. Renou, L. (1932): „A propos du subjonctif vedique“ in Bulletin de la société de linguistique de Paris 33 pp. 5-30 Rix, H. (1986): Zur Entstehung des urindogermanischen Modussystems. Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachwissenschaft. Szemerenyi, O (1966): “ The Origin of the Vedic ‘Imperatives’ in –si” in Language 42, I, pp. 1-6. (1989) Einführung in die vergleichende Sprachwissenschaft. Darmstadt: WBG. Tichy, E (2002): „Zur Funktion und Vorgeschichte der idg. Modi” in Indogermanische Syntax-Fragen und Perspektiven, Ed. Hettrich, H. pp. 189ff. (2004): “ Gr. , lat. t und die Mittelzeile der Duenos-Inschrift” in Glotta LXXVIII 1-4, pp. 179-202. 11