A MARKETING MODEL FOR A SOFTWARE FIRM by MARCO VILLA

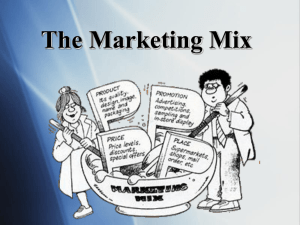

advertisement