Cryptic population structuring in Scandinavian lynx: reply to Pamilo

advertisement

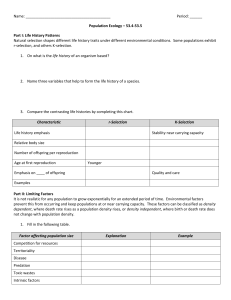

Molecular Ecology (2006) 15, 1189– 1192 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02782.x COMMENT Blackwell Publishing Ltd Cryptic population structuring in Scandinavian lynx: reply to Pamilo P . E . J O R D E ,*† E . K . R U E N E S S ,* N . C . S T E N S E T H * and K . S . J A K O B S E N * *Centre for Ecological and Evolutionary Synthesis (CEES), University of Oslo, PO Box 1066 Blindern, N-0316 Oslo, Norway, †Institute of Marine Research, Flødevigen Research Station, N-4817 His, Norway Abstract In a recent Commentary in this journal, Pamilo (2004) criticized our analysis of the spatial genetic structure of the Eurasian lynx in Scandinavia (Rueness et al. 2003). The analyses uncovered a marked geographical differentiation along the Scandinavian peninsula with an apparent linear gradient in the north–south direction. We used computer simulations to check on the proposition that the observed geographical structure could have arisen by genetic drift and isolation by distance in the approximate 25 generations that have passed since the last bottleneck. Pamilo disapproved of our choice of population model and also how we compared the outcome of the simulations with data. As these issues should be of interest to a wider audience we discuss them in some detail. Keywords: computer simulations, genetic structure, isolation by distance, lynx, recolonization Received 5 September 2005; revision accepted 23 September 2005 Background ‘How cryptic is the Scandinavian lynx?’ asks Pamilo in his commentary published in Molecular Ecology last year (Pamilo 2004). His paper is a critique of our paper entitled ‘Cryptic population structure in a large, mobile mammalian predator: the Scandinavian lynx’ (Rueness et al. 2003) published in the same journal. Pamilo’s criticism contains several misunderstandings and errors, and in this reply we address the more general ones. Additional details will be provided by the authors upon request. The genetic population structuring of the Scandinavian lynx, first described by Hellborg et al. (2002), is surprisingly pronounced, given the high mobility of the species and the short time since recolonization, presumably since the 1950s. Aiming at a deeper understanding of the differentiation mechanism(s), Rueness et al. (2003) expanded on the previous analysis and included additional samples from Scandinavia. The earlier study by Hellborg et al. (2002) included 29 individuals with only approximately known Correspondence: Per Erik Jorde, Fax: +47 37 05 90 01; E-mail: p.e.jorde@bio.uio.no © 2006 Blackwell Publishing Ltd sampling locations, and these individuals could for that reason not be included in the later analysis, which focused on fine-scaled geographical structure. In addition to a common central Scandinavian lynx population, Rueness et al. (2003) demonstrated the occurrence of two distinct groups or populations: one in southern Norway and one in the northernmost part of Scandinavia. Combining the population genetic patterns we observed, through both individual-based and frequency-based genetic analyses, with information about history, geography and lynx biology, we concluded that the population history of the Scandinavian lynx most likely is more complex than earlier assumed. In particular, we found with the aid of computer simulations that the observed pattern was not likely to have arisen after migration from a hypothetical single source population in the brief time span available. Choice of simulation model The pattern of genetic differentiation in lynx in Scandinavia was found to increase linearly with geographical distance. Because such a linear pattern is expected theoretically in a standard one-dimensional stepping-stone model, we chose this model as a basis for our computer simulations. The 1190 P . E . J O R D E E T A L . Table 1 FST/(1 – FST) and its slope simulated with different total population array length (number of population units). The computer simulations were carried out as described in Rueness et al. (2003), using Ne = 25, t = 25 generations, and averaging over 10 000 replicate runs. Simulated population array length Distance 5 10 100 1000 1 step 2 steps 3 steps 4 steps Slope 0.068 0.104 0.133 0.161 0.031 0.066 0.098 0.121 0.139 0.024 0.065 0.093 0.113 0.127 0.021 0.065 0.092 0.112 0.126 0.020 Note that the simulated slopes are identical or nearly so for all array lengths, except for the very shortest one (with five populations). The latter reveals inflated FST values between the terminal populations (four steps apart), probably caused by these populations receiving only half the number of immigrants (three instead of six per generation). This ‘edge-effect’ probably has no counterpart in real lynx populations, which receive immigrants from outside Scandinavia, at least in the north (Rueness et al. 2003). simulations aimed at testing the null hypothesis that the present genetic structure in Scandinavian lynx has arisen by random genetic drift and geographically restricted gene flow, after expansion from a single source population some 25 generations ago. We initiated the population array with equal allele frequencies in all populations in order to study how rapid genetic differentiation builds up from an undifferentiated source population. Biologically, this initial condition represents the situation where the source population expands rapidly to fill the vacant habitat, corresponding to the ‘radiation’ model of Slatkin (1993: p. 267). There is thus no discrepancy between our verbal hypothesis on one hand and our simulation model on the other, as claimed by Pamilo. The standard stepping-stone model assumes a long array of populations (and is sometimes made to be circular) to avoid ‘edge effects’ caused by the terminal populations (Table 1; Maruyama 1970). We used an arbitrary length of 100 populations in the simulations, but studied differentiation among neighbouring five populations only, i.e. populations separated by at most four migration steps. Pamilo claims that such a long (100) chain of connected populations approaches drift–migration equilibrium much more slowly than an array with only five populations. This is a misunderstanding because the total length of the population array has little influence on the building up of genetic differentiation among nearby populations (Fig. 1; see also Slatkin 1993). The amount of differentiation between populations separated by a given distance at a given time Fig. 1 Results of computer simulations depicting the approach towards drift–migration equilibrium in a finite stepping-stone model (length = 100 populations of size N = 25). The dashed lines represent FST/(1 – FST) values after t generations, starting with uniform allele frequencies at t = 0. The solid line represents the theoretical equilibrium slope of 1/(4Nm) or 0.043. is therefore largely independent of the length of the total population array (Table 1). The simple stepping-stone model obviously cannot capture all the details of the real situation (nor is it supposed to), but has the important virtue of requiring very few parameters. Namely, just m, the rate of exchange among neighbouring populations, and Ne, the effective size of local populations. (The standard stepping-stone model also includes an additional long-distance rate, minf, but this term only lowers the overall amount of differentiation and was therefore ignored.) To evaluate the genetic pattern expected from this model, we simulated all realistic values of Ne (12–200) and used an empirical estimate for M (the product of m and Ne). As Pamilo observes, the estimation of M assumes that the Scandinavian lynx populations are in drift–migration equilibrium. As discussed in our original paper, this assumption is reasonable under the present null hypothesis because the observed pattern is linear as far as can be determined (cf. Figure 4 in Rueness et al. 2003), and it would not be linear had it not yet reached equilibrium (cf. Fig. 1). This is so if the null hypothesis is correct. If it is not, then a linear relationship may or may not arise outside equilibrium, but in such situations the null hypothesis should be rejected anyway, as was indeed the case. Pamilo obviously concur with our approach of using computer simulations to evaluate the mechanisms behind the present genetic structure of Scandinavian lynx. He also, © 2006 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Molecular Ecology, 15, 1189– 1192 L Y N X P O P U L A T I O N S T R U C T U R E 1191 implicitly, agrees with the basic structure of our model, in which the elongated Scandinavian peninsula is partitioned into five geographical areas or ‘populations’ in a linear configuration. Where our approaches differ is that we choose the simplest model that could possibly explain the data and evaluate that model over the (almost) entire parameter space of the only free variable (Ne) in the model. This evaluation was necessary because the real values are very poorly known. Pamilo, in contrast, takes a different approach and apparently tries to find a model that best fits the data. His model introduces several additional parameters (a population growth rate, a carrying capacity, and four different migration rates) with fixed, arbitrary values. Pamilo’s ad hoc approach is useful to demonstrate what is possible, but is problematic when the purpose is to test hypotheses; if his model had been rejected by the data, how many other parameters values or model variations should be tried? Comparing computer simulations with data The slope of FST/(1 – FST) against distance in a onedimensional habitat is robust to geographical scaling and depends only on dispersal (Rousset 1997). Consequently, we compare simulations and data by comparing the simulated slopes to the observed one. The comparison must take uncertainty (sampling errors) into account and there are two different approaches that may be taken to do this. First, one may do as Pamilo did and simulate the uncertainty that can be expected from sampling a finite number of loci (and individuals) for genetic analysis. In the comparison the observed slope is then regarded as a fixed value and one checks if it lies within the simulated range, say within the range that includes 95% of the simulations. Alternatively, one may follow the more conventional hypothesis testing route, as we did, and use the uncertainty of the estimated slope. In this latter approach the simulated slope is regarded as a fixed value, being averaged over a sufficiently large number of computer runs to eliminate stochastic variability. The simulated value thus represents the expected value under the stipulated null hypothesis and one then checks if this expected value lies within, say, the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the observed slope. Both of the above approaches to compare simulation results with data can be used, but both also have potential problems with adequately describing sampling variability. In the first approach it is unpractical to (and Pamilo did not) take into account differences among loci in number of alleles and allele frequency profiles, as well as different sample sizes across the study area. These factors all affect the variability among computer runs and therefore the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis. The second approach implicitly includes most of these sources of sampling errors, but it is not clear how to best calculate CI from © 2006 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Molecular Ecology, 15, 1189–1192 the data. Problems arise because the data consist of pairwise measures (FST), and the measures are thus not all independent. In our original paper we used the traditional method of calculating CI, which assumes independence among measures. Using that method we got a 95% CI for the slope from 0.000129 to 0.000176 per km (corresponding to 0.036–0.050 per population step of 283 km). We get reasonably similar results, however, if we instead jackknife over populations (yielding 95% CI from 0.000094 to 0.000209) or bootstrap over independent population pairs (0.000100– 0.000337), using the ibdws version 2.0 Beta software (Jensen et al. 2005). The steepest slope in our simulations, b = 0.00010 per km, which occurred for Ne = 12, lies just at the lower limit of these new CIs and should probably still be judged significant in a one-sided test. (A one-sided test is appropriate because the alternative hypothesis is that the simulated slope is less than the observed one.) It is unclear which of these procedures, if any, is to be preferred for calculating CI from pairwise data, and it is beyond the scope of this note to resolve this issue. At any rate, Pamilo’s claim that we did not take stochastic variation into account is incorrect. Concluding remarks As we have shown in this commentary, our original analysis was appropriate. It was unfortunate that Pamilo’s commentary was published without our consultation and that it contains a number of misunderstandings. Pamilo’s model does nevertheless represent an interesting alternative to, although not necessarily more realistic than, our model. Because the two models, representing different hypotheses about the lynx recolonization process in Scandinavia, led to different conclusions despite being based on the same data, it seems that FST in the present case does not contain enough information to distinguish among alternative hypotheses. This sobering lesson may reflect a more general fact and should be kept in mind also in other studies. Nevertheless, when additional evidence, as presented and discussed in detail in the original paper, is brought into consideration, an origin from multiple sources remains the most likely scenario for the present lynx populations in Scandinavia. References Hellborg L, Walker CW, Rueness EK et al. (2002) Differentiation and levels of genetic variation in northern European lynx (Lynx lynx) populations revealed by microsatellites and mitochondrial DNA analysis. Conservation Genetics, 3, 97–111. Jensen JL, Bohonak AJ, Kelley ST (2005) Isolation by distance, web service. BMC Genetics, 6, 13 (http://phage.sdsu.edu/∼jensen/). Maruyama T (1970) Analysis of population structure. I. Onedimensional stepping-stone models of finite length. Annals of Human Genetics, London, 34, 201–219. 1192 P . E . J O R D E E T A L . Pamilo P (2004) How cryptic is the Scandinavian lynx? Molecular Ecology, 13, 3257– 3259. Rousset F (1997) Genetic differentiation and estimation of gene flow from F-statistics under isolation by distance. Genetics, 145, 1219–1228. Rueness EK, Jorde PE, Hellborg L, Stenseth NC, Ellegren H, Jakobsen KS (2003) Cryptic population structure in a large, mobile mammalian predator: the Scandinavian lynx. Molecular Ecology, 12, 2623–2633. Slatkin M (1993) Isolation by distance in equilibrium and nonequilibrium populations. Evolution, 47, 264 – 279. The data behind the present work was generated as a part of Eli K. Rueness’ PhD thesis. She is now a post doc working on the molecular ecology of lynx and other species. Per Erik Jorde is a population geneticist focusing on temporal genetic change and spatial genetic structure. He performed the computer simulations in this and in the original paper. Nils Chr. Stenseth, head of the CEES (http://biologi.uio.no/cees/), is a population biologist working on marine, freshwater and terrestrial systems. Kjetill S. Jakobsen is an evolutionary geneticist with particular interest in the interplay between ecology and genetics. © 2006 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Molecular Ecology, 15, 1189– 1192