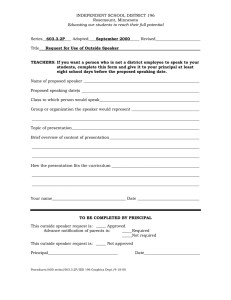

Document 11354467

advertisement