Marketing Education: Experiencing New Frontiers MARKETING EDUCATORS’ ASSOCIATION

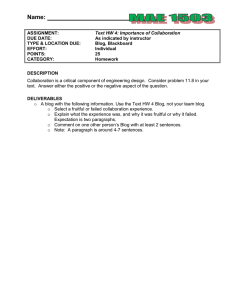

advertisement