Drivers of Organizational Commitment

Academic Article Winter 2009 25

By Scott B. Friend, Danny N. Bellenger, and James S. Boles

The purpose of this manuscript is to explore drivers of commitment within sales organizations and to document the results based on the antecedents and context-dependent conditions. The goal of this article is to provide researchers and managers a unifying guide regarding salesperson organizational commitment, as well as alert researchers of equivocal path relationships which may need future investigation. To accomplish this, a comprehensive review of published academic sales literature was conducted. This review provided the basis for a model of the salesperson driver-commitment relationship and the different contextual scenarios which may modify these linkages.

An Introduction to Commitment

Attempting to identify what drives salesperson organizational commitment has been a consistent challenge for both practitioners and academics. The concept of commitment is of strong interest because it has been linked to turnover and organizational performance.

Barksdale et al. (2003) note that commitment is particularly unique and relevant in the salesforce because top performing salespeople view themselves as an asset whose value is not related to the firm they work for, but instead attributed to their individual ability to sell.

Managers need to understand mechanisms and characteristics which facilitate the commitment of top sales performers in their selling (Flaherty et al. 1999), turnover intentions (Johnston et al. 1990; Bashaw &

Grant 1994), absenteeism (e.g., Farrell &

Stamm 1988), and job satisfaction (e.g., Low et al. 2001; Schwepker 2001). In sum, employee

Scholl 1981). commitment influences organizational effectiveness (Schein 1970;

This review is the first to provide an exhaustive conceptual summary of the broad array of drivers of organizational commitment within the sales literature. The goal of this manuscript is to identify antecedents of commitment found in sales research, while simultaneously taking notice of the definition, measurement instruments and moderating firm because, the goal of sales management can be summarized as creating a sales force of variables captured in various studies in order to identify potential drivers of the equivocal high performers who are also highly findings. committed to the sales organization.

Commitment Defined

The risks associated with the salesperson’s attributions of personal value are relevant within modern salesforce research, such as a firm’s risk associated with salesperson owned loyalty (Palmatier et al. 2007) and key contact employee turnover (Bendapudi & Leone

2002). Jaramillo et al.’s (2005) meta-analysis cites job performance characteristics that are influenced by salesperson organizational commitment; including, customer-oriented

Bashaw and Grant (1994, p.43) identified and defined three dimensions of commitment: job, career and organizational. While each of these concepts are important, organizational commitment is the most referenced construct identified within the sales literature and provides the desired link to the retention of top performers. Jaramillo et al. (2005, p.706) identify two approaches organizational commitment: to defining

Vol. 9, No. 1

26 Journal of Selling & Major Account Management

First, commitment is understood as an employee’s intention to continue working in the organization (e.g., Meyer 1997). Second, organizational commitment may be defined as an attitude in the form of an attachment that exists between the individual and the organization, and is reflected in the relative strength of an employee’s psychological identification and involvement with the organization (Mowday et al. 1979).

The two approaches discussed by Jaramillo et al. (2005) are respectively synonymous with the behavioral and attitudinal approach of classifying organizational commitment (Chonko 1986).

Salesperson attitudinal commitment, which is more commonly cited, refers to the individual salesperson’s general orientation toward the organization (Chonko 1986); including the employee’s desire to remain with the organization, desire to exert high levels of effort on behalf of the organization and identification with the organization’s goals

(Scholl 1981).

Commitment Measured

Jaramillo et al. (2005) identify the organizational commitment questionnaire

(Porter et al. 1974; Meyer et al. 1993) as the measurement instrument of choice within their meta-analysis. While this scale may be the most prevalent, it is not the only scale used to measure commitment. Table 1 identifies the commitment scales used in salesforce research and provides the frequency with which certain scales are used. Table 1 visually confirms the dominance of two primary measurement scales: (1) the

Organizational Commitment Questionnaire

(Porter et al. 1974; Mowday et al. 1979) and

(2) the four-item scale developed by Hunt et al. (1985).

Antecedents to Commitment

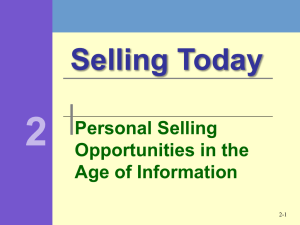

A large variety of antecedents in many different contextual environments are related to salesperson commitment. Four antecedent

Northern Illinois University groups have received attention in the sales literature and are consistent with Scholl’s

(1981) summarization of the drivers of organizational commitment: (1) supervisor relationships, (2)sales organization characteristics,

(3) sales task characteristics and (4) personal characteristics. Figure 1 is a summary model of the forthcoming review regarding the relationships among salesperson organizational commitment, the four categorical drivers, and a number of potentially impactful contextual variables.

Supervisor Relationships

Supervisor relationships are an important mechanism for integrating subordinates into the organization and helping a salesperson develop a sense of personal commitment

(Katz & Kahn 1978; Chonko 1986). This literature synthesis focuses on characteristics of the supervisor-salesperson relationship, such as salesperson trust in the supervisor, communication, and leadership style.

Trust in Supervisor : Trust is depicted as the salesperson’s perception of his or her supervisor’s credibility and benevolence

(Flaherty & Pappas 2000). Morgan and Hunt

(1994) explain the relationship between trust in one’s supervisor and commitment by noting that individuals prefer trusting work relationships, and will commit themselves to the organization to a greater degree when this trust exists (Brashear et al. 2003). A review of the literature regarding salesperson-sales manager trust indicates a number of mechanisms which may be driving the relationship. Flaherty and Pappas (2000) found that while trust appears to be driven by both sales manager procedural justice and distributive justice, it is procedural justice that plays a significantly larger role in forming salesperson trust in their supervisor. This relationship between procedural justice and trust in the sales manager was maintained across career stages. However, salespeople in the exploration, maintenance, or disengagement

Academic Article Winter 2009 27

Table 1. Cited Commitment Measurement Scale and Their Reported Reliabilities

Studies

AC

Or-

Agarwal (1993)

Agarwal (1999)

Amyx & Alford (2005)

Babin et al. (2000)

9 0.85

9 NR

4 0.75

N R 0.89

Barksdale et al. (2003)

Bashaw & Grant (1994)

Boshoff & Mels (1995)

Boyle (1977)

6 0.87

4 0.77

7 0.76

4 0.77

4 0.91

8 0.92

6 0.87

Brashear et al. (2006)

Chu-Mei (2007)

Dubinsky & Mattson (1979)

Dubinsky & Skinner (1984)

Dubinsky et al. (1992)

Farrell (2005)

Flaherty & Pappas (2000)

Grant et al. (2001)

Huddleston et al. (2002)

Hunt et al. (1985)

4 0.75

6 0.89

1 NA

4 0.80

15 0.90

15 0.86

15 0.86

Dubinsky et al. (1993)

Dubinsky et al. (1997) - Japan (top);

US (bottom)

Evans et al. (2002)

15 0.92

7 0.85

9 0.92

9 0.98

9 0.90

5 0.77

4 0.85

15 0.91

Ingram et al. (1989)

Johlke & Duhan (2001)

Johlke et al. (2000)

4 0.84

4 0.80

4 0.80

Johnston et al. (1990)

MacKenzie et al. (1998)

15

15

NR

0.87

McColl-Kennedy & Anderson (2005) 4

McNeilly & Goldsmith (1991) 14

NR

0.87

Moideenkutty et al. (2001)

Pettijohn et al. (2007)

Rhoads et al. (1994)

Roberts & Chonko (1999)

Roberts & Coulson (1999)

Russ & McNeilly (1995)

Sager & Johnston (1989)

3 0.86

X

15 0.79

6 0.77

4 0.84

4 0.86

14 0.92

15 0.87

5 0.79

Schaefer & Pettijohn (2006)

Schul & W ren (1992)

Siguaw & Honneycutt Jr. (1995)

Singh (1998)

Tyagi & W otruba (1998)

W aters (2007) - Voluntary redundant

(top); Involuntary (bottom)

W atson & Papamarcos (2002)

W eeks et al. (2004) - US

W eeks et al. (2006) - Mexico

Yilmaz (2002)

5 0.90

13 0.91

15 NR

4 0.83

15 0.92

6 0.88

6 0.85

15 0.88

4 0.86

4 0.86

4 0.88

9 0.92

*

X

X

X

Commitment Scales

X

X

X

*

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

*

*

X

X

= Affective ganizational

Vol. 9, No. 1

28 Journal of Selling & Major Account Management

Figure 1. A Model of Salesperson Organizational Commitment

Job

Characteristics

Culture

Context

Performance

Rewards

Organi zational

Cli mate

Supervisor Behaviors:

•Trust

•Communication

•Leadership Style

Organization Characteristics:

•Fairness

•Ethical Climate

Career

Stage

Salesperson

Organizational

Commitment

Task Characteristics:

•Role Stress

•Job Satisfaction

Personal Characteristics:

•Gender

•Age

•Education stages of their career did not possess a perceived relationship between distributive justice and trust. Only when salespeople were in the establishment stage did distributive justice have a significant effect on trust.

Flaherty and Pappas (2000) conclude the trust construct can act as a mediator between fairness and organizational commitment, as well as job satisfaction and commitment.

Watson and Papamarcos (2002) also report that trust in management positively and significantly influences organizational commitment. Watson and Papamarcos (2002) looked at trust alongside reliable communication and positive perceptions of normative frameworks. The combination of communication reliability and trust in management outperformed demographics in regard to explaining significant levels of variance in organizational commitment.

Communication : Effective sales manager communication, defined by frequency, formality, content indirectness, and bidirectional movement, may be among the most powerful tools for improving firm outcomes (Johlke &

Northern Illinois University

Duhan 2001). Johlke and Duhan (2001) demonstrate that among their three competing models, the PEO model has the highest explanatory power. The PEO model is essentially a four stage process in which sales manager communication quality is associated with salesperson communication satisfaction, and communication satisfaction is positively associated with a salesperson’s organizational commitment. Additionally, Johlke et al. (2000) further support the effects of a sales manager’s pattern of communication influencing a salesperson’s organizational commitment, specifically through ambiguity, job performance, and job satisfaction

While the operationalization of communication patterns varies across studies, the relationship appears to be robust when considering the variety of measurement scales of organizational commitment; Johlke et al. (2000) relied on the

4-item scale adapted from Hunt et al. (1985) while Watson and Papamarcos (2002) used the

15-item OCQ scale as specified by Mowday et al. (1979).

Academic Article

Leadership Style :

Many researchers include leadership style in their assessment of commitment based on findings by Johnston et al. (1990), which shows that leadership role clarification and leadership consideration positively affect organizational commitment in the early stages of employment (Brashear et al. 2006). Boshoff and Mels (1995) note that salespeople who believe their leaders to be considerate, compared to those who do not, have greater organizational commitment. This relationship is supported indirectly through the construct of role conflict; suggesting that organizational commitment can be enhanced if supervisors adopt a more considerate leadership style, thus reducing role conflict.

However, McColl-Kennedy and Anderson

(2005) found that supervisor leadership failed independent tests of a direct relationship with organizational commitment. Further, they also found that the highest levels of commitment were experienced when female and male sales representatives were teamed up with female managers, indicating potential gender effects.

Additional Factors : There are additional variables associated with the relationship between supervisor characteristics and commitment. For example, Brashear et al.

(2006) test four different types of mentors in the sales setting, and their differing effects on salesperson commitment. Additionally, Evans et al. (2002) and Amyx and Alford (2005) both look at perceptual congruency between the salesperson and the sales manager; however their differing perspectives of congruency provides limited means of comparing the results across studies.

Sales Organization Characteristics

Amyx and Alford (2005) state that organizations fail to develop long-term relationships with their salespeople because of employee perceptions that the organization is not genuinely concerned with the welfare of

Winter 2009 29 their salespeople. These salespeople in turn resist organizational commitment; resist accepting organizational goals and resist achieving performance goals. Wiener (1982) summarizes the organizational determinants of salesperson organizational commitment based on two categories: (1) values of loyalty and duty and (2) individual-organization value congruency. Emphasis is placed on individualorganizational value congruency because organizations can control this relationship through socialization (Dubinsky et al. 1986 ).

In line with this determinant, we have identified two recurring themes in the literature which offer the opportunity for comparison across studies. These themes are organizational fairness and ethical climate.

Organizational Fairness : Organizational fairness is a measure of perceived equity of the salesperson’s inputs to rewards received

(Dubinsky et al. 1993). The generally supported relationship indicates that the higher a salesperson’s level of perceived organizational fairness, the higher the degree of commitment.

Dubinsky et al. (1993) extends support for the positive relationship between organizational fairness and organizational commitment based on a sample of Japanese sales personnel - a culture which is equity oriented. These components include pay level and latitude; however pay rules, pay administration, rule administration, work pace, and distribution of tasks are not significantly related. Further research shows that higher order needs (e.g., promotion, recognition and incentives equity) can be even more important to a salesperson’s organizational commitment rather than lower order needs (i.e. salary and raise) (Roberts &

Chonko 1999).

Organizational fairness can be conceptualized as having two dimensions – procedural justice and distributive justice. Roberts and Coulson

(1999) summarize these by identifying their traits. Procedural justice includes pay

Vol. 9, No. 1

30 Journal of Selling & Major Account Management administration, rule extensions, work pace, and latitude; while distributive justice includes more outcome based traits such as pay rules, distributing tasks and pay levels. Roberts and

Chonko (1999) contest previous research (e.g.,

McFarlin & Sweeney 1992) by stating that the outcome (distributive justice) of the sales management’s decision process was more important in explaining organizational commitment than was the procedure used to arrive at the outcome (procedural justice).

Roberts and Coulson’s (1999) findings support this viewpoint. Further, the authors’ show an interaction effect between these two forms of equity in that the effect of distributive justice on organizational commitment is stronger in conditions of low perceived procedural justice than in high perceived procedural justice conditions. Moideenkutty et al., (2001) extend this relationship by including perceived organizational support as a mediating variable; findings show that perceived organizational support fully mediates the effect of procedural justice on affective commitment.

Organizational fairness can also be studied in the context of internal equity, which is positively related to commitment, but demonstrates varying degrees of strength. Roberts and

Chonko (1999) and Roberts and Coulson (1999) indicate that while external equity accounts for

10% of the variance of organizational commitment, internal equity accounts for 14%, and explains more of a salesperson’s organizational commitment. Specifically, of the six facets capturing internal perceptions of equity, perceptions of promotions equity was most important to organizational commitment; while of the five external equity facets, only perceptions of recognition was significant

Ethical Climate: Through ethical climate, sales employees learn the appropriate organizational expectations with respect to moral conduct

(Babin et al. 2000). Weeks et al. (2004) report a firm’s ethical climate is positively related to a

Northern Illinois University salesperson’s organizational commitment - supporting the findings of Babin et al. (2000) and Schwepker (2001). Thus, as stated by

Weeks et al. (2004), individuals who perceive that their organizations are trying to improve the ethical climate should exhibit stronger commitment to that organization, particularly if these ethical values are congruent with their own. However, Weeks et al. (2006) extend this relationship into a cross-cultural comparison of Mexico and the United States, finding that the relationship does not hold across cultures.

While ethical climate positively influences commitment for US salespeople, there is no significant relationship for Mexican salespeople

Additional Factors: While additional organizational characteristic variable groupings are intermediately present, such as organizational support and organization culture, there are not enough published findings to include in this comparative analysis of the sales literature.

These relationships may require further research across contextual settings to improve generalizations or identify contradictory findings.

Sales Task Characteristics

Sales task characteristics encompass role stress and job characteristics (Mathieu & Zajac

1990). Wiener (1982) identifies the following factors as job characteristics: job challenge, feedback, opportunity for social interaction, task identity, group attitudes, and organizational dependability.

Role Stress : Role stress is a form of tension resulting from the job (Kahn et al. 1964) and is representative of role status. Role conflict and ambiguity act as stressors which have a depressing impact on behavioral and psychological job outcomes, such as commitment (Singh 1998). Role ambiguity is likely to occur when a salesperson does not understand the activities, or the importance of these activities, that he or she should perform

Academic Article as a part of his or her job (Walker et al. 1972;

Behrman & Perreault 1984). On the other hand, role conflict occurs when a person experiences job demands or expectations that are incompatible from his or her identified role (Dubinsky & Mattson 1979). The literature search specific to sales personnel indicates that a majority of the articles hypothesize and support a negative relationship for role ambiguity (Dubinsky et al. 1992; Rhoads et al. 1994; MacKenzie et al.

1998; Grant et al. 2001; Barnes et al. 2006) and role conflict (Boshoff & Mels 1995;

MacKenzie et al. 1998; Barksdale et al. 2003) with commitment . However, while these two constructs are often measured together because both tend to predict lower levels of commitment (Johnston et al. 1990; Dubinsky et al. 1992), divergent findings within this assumed relationship are present.

In regard to role ambiguity’s relationship with commitment, Dubinsky and Mattson (1979) suggest that past research is inconsistent. The variance among research hypotheses identified in this search supports this statement. Singh

(1998) hypothesized an inverted U-type relationship between role ambiguity and organizational commitment, as well as for the relationship between role conflict and organizational commitment, based on past research and activation theory. Dubinsky and

Mattson (1979) proposed a non-significant relationship between role conflict and commitment based on past equivocal findings.

Finally, majority of remaining sales-related articles hypothesized a negative relationship between role ambiguity and commitment (e.g.,

Dubinsky & Mattson 1979; Johnston et al.

1990; Grant et al. 2001) and role conflict and commitment (e.g., Dubinsky & Mattson 1979;

Dubinsky et al. 1992; MacKenzie et al. 1998;

Barksdale et al. 2003).

Rhoads et al. (1994) found support for a negative relationship between role ambiguity and organizational commitment; however, the

Winter 2009 31 researchers divided role ambiguity into internal ambiguity (e.g., company flexibility, company proportion, boss demands) and external ambiguity (e.g., customer interaction, customer objection, customer presentation, family). They move away from the characteristically supported relationship at the global level and show that the internal ambiguity subset is the only predictor of organizational commitment, thus excluding external ambiguity. The results from two studies indicate a non-significant relationship

(Johnston et al. 1990; Boshoff & Mels 1995).

While these two studies found the direct path between role conflict and organizational commitment nonsignificant, both found a significant indirect path. Johnston et al. (1990) indicate that role conflict has a significant indirect effect on commitment through role ambiguity and job satisfaction, while Boshoff and Mels (1995) indicate that the relationship is significant only when participation in decision making is included as a moderating variable.

Dubinsky and Mattson (1979) included both role ambiguity and role conflict in their research and examined moderating relationships for both constructs. Age and education were identified as having an effect on the relationship between role ambiguity and commitment. Specifically, the results claim that the relationship was stronger for those age 31-50 compared to those 16-30.

Likewise, the negative relationship between role ambiguity and commitment was stronger for those with less formal education than those with more formal education. Similar relationships have not been corroborated in further published findings, thus this particular relationship needs further investigation to fully understand the generalizability of the impact of age on role ambiguity/role conflict and organizational commitment. Finally,

Dubinsky and Mattson (1979) indicate that experience and job satisfaction reduced the relationships for both role ambiguity and role conflict with organizational commitment.

Vol. 9, No. 1

32 Journal of Selling & Major Account Management

Dubinsky et al. (1992) included both role ambiguity and role conflict in their crosscultural analysis of the potential effects in the

United States, Japan and Korea. The researchers found no significant differences in the relationship between ambiguity and commitment across these countries. However, the hypothesized relationship between role conflict and organizational commitment was only supported in the United States and Japan; the relationship was not significant in Korea.

Agarwal (1993) extends the concept of potential cultural influences on role ambiguity and role conflict by examining the relationships in LPD/HI (low power distance/high individualism) versus HLP/LI

(high power distance/low individualism) cultures. The results support the hypothesis that the negative relationship between role ambiguity and organizational commitment is stronger in LPD/HI cultures than HPD/LI cultures. However, identical hypotheses in regard to role conflict and organizational commitment were not supported for the stronger relationship in LPD/HI cultures than

HPD/LI cultures.

Singh (1998) suggested that job characteristics

(e.g., feedback, participation, variety and autonomy) serve as an indicator of the inverted U-shaped relationship between role ambiguity/role conflict and organizational commitment. An extremely low level of job ambiguity indicates a low level of task variety and job roles detailed through procedural guidelines, which can also lead to increased job tension. Singh (1998) found that an inverted U-shaped relationship exists between role ambiguity and organizational commitment, with task variety serving as a proxy for explaining this relationship.

Job Satisfaction: The relationship between job satisfaction and commitment represents a classic debate among scholars pertaining to the ordering of effects. For an in-depth review and analysis of the various research outcomes

Northern Illinois University of this relationship, Brown and Peterson

(1993) provide a meta-analysis summarizing research specific to the job satisfaction and commitment relationship. Results indicate that job satisfaction positively affects commitment.

Many works have found a positive relationship which moves from job satisfaction to commitment; specifically, Barksdale et al. (2003), Dubinsky and Skinner (1984), Dubinsky et al. (1992),

Grant et al.(2001), Mackenzie et al. (1998), and

Johnston et al. (1990) each confirm the positive causal relationship. Representative of the strength of the satisfaction-commitment relationship, Dubinsky and Skinner (1984) indicate that job satisfaction explained 26% of the variance in organizational commitment.

Yilmaz (2002) provides a unique perspective by separating job satisfaction into intrinsic and extrinsic forms. The author compares the strengths of intrinsic satisfaction to extrinsic satisfaction, as well as test potential moderating relationships of age and organizational tenure. Results indicate that intrinsic job satisfaction is a stronger driver of a salesperson’s affective commitment, and that the impact of intrinsic job satisfaction was not moderated by career stage. The positive relationship between extrinsic job satisfaction and affective commitment for early career salespeople was significantly stronger than for late-career salespeople. In addition, Yilmaz

(2002) assessed two forms of commitment, affective and continuance. Differences exist in that internal job satisfaction relates only indirectly to continuance commitment through its impact on affective commitment; while external job satisfaction was found to exert both a direct and indirect influence on continuance commitment. Finally, external job satisfaction resulted in a stronger impact on continuance commitment among high performing salespeople (as opposed to low) and full commission salespeople (as opposed to salary plus commission).

Academic Article

Additional Factors: Role stress and job satisfaction are fairly representative of the sales task characteristics category, however there remain two specific categories of variables which appear to be underrepresented in the sales literature related to commitment – job involvement and job characteristics. As a result, the relationship between organizational commitment and job involvement, as well as the effects of specific job characteristics (e.g., challenge, feedback, opportunity, social interaction, task identity), were not discussed in this review due to their limited coverage within the sales literature.

Personal Characteristics

Personal characteristics, such as gender, age and education, have been shown to affect a salesperson’s organizational commitment across numerous contexts (Bashaw & Grant 1994); however, this set of drivers represents the highest degree of equivocal findings.

Gender: While the environmental associations surrounding gender within the salesforce has likely diminished over time as social values have changed (i.e., gender-role conflict) and as women’s role in the workforce has become increasingly widespread and accepted (Koberg

& Chusmir 1987), it is still likely that interaction effects exist which influence the basic relationship between gender and organizational commitment. While some research indicates that it is not necessarily gender itself which affects organizational commitment, but rather characteristics such as the job task (Dubinsky et al. 1993; Lefkowitz

1994), there exists a significant amount of alternative research which proposes a direct or mediated relationship between gender and organizational commitment. Within the salesforce literature Busch and Bush (1978) and

Swan et al. (1978) indicate that the evidence of gender differences is ambiguous.

Researchers, such as Bashaw and Grant (1994) and Tyagi and Wotruba (1998), pose that

Winter 2009 33 female salespeople have greater organizational commitment, while others such as Schaefer and Pettijohn (2006) found opposite effects.

Furthermore, Schul and Wren (1992) and

Siguaw and Honeycutt Jr. (1995) indicate no significant differences among males and females in their level of commitment. These highly divergent findings provide cause for further investigation.

Our review finds that commitment is not consistently operationalized throughout these studies, which may account for some of the inconsistent findings. At a deeper level than the scale used to study the relationship, it is possible that characteristics associated with the organization may interact with the gendercommitment relationship. Tyagi and Wotruba

(1998) indicate that female salespersons demonstrate greater job commitment than males; however they also show that females perceived the organizational climate more favorably, as well as indicate a stronger emphasis on organizational identification.

In addition to associations with the organization, characteristics specific to the job may exists at varying levels between the two genders. Siguaw and Honeycutt (1995), who found no significant organizational commitment gender differences, report that women had lower role ambiguity and role conflict. Further, characteristics associated with supervisors may play a moderating role in the gender-commitment relationship. Russ and McNeilly (1995), indicate that supervisor relationships will have more of an impact on the organizational commitment of female sales representatives.

When additional personal characteristics, such as experience and education are included as covariates, few gender differences may actually materialize (Busch & Bush 1978; Schul &

Wren 1992).

Age : Numerous researchers predict a positive relationship between age and commitment - as salespeople get older they will be more committed (Steers 1977; Angle & Perry 1983;

Vol. 9, No. 1

34 Journal of Selling & Major Account Management

Hunt et al 1985; Pierce & Randall 1987;

Bashaw & Grant 1994). This positive relationship is attributed to the development of personal identification (Hall et al. 1970;

Buchanan 1974), career development and a mature orientation of the salesperson (Cron

1984; Cron & Slocum 1986), limited alternatives and sunk costs in later years, and increasing job satisfaction due to receiving better positions and higher pay (Huddleston et al. 2002). However, there are inconsistencies in the findings concerning the age-commitment relationship results.

The predicted positive relationship between age and commitment was non-significant in two studies (Sager and Johnston 1989; Tyagi and Wotruba 1998). In comparison,

Huddleston et al. (2002) found support for the hypothesized positive relationship between age and organizational commitment. Potentially impactful, Huddleston et al. (2002) measured commitment using a scale developed by Cook and Wall (1980), while Sager and Johnston

(1989) and Tyagi and Wotruba (1998) used comparative scales, respectively citing

Mowday et al. (1979) and Porter et al. (1974).

Beyond the scales, Schaefer and Pettijohn (2006) shed light on the potential inconsistencies among the predicted linear relationships as they indicate the relationship may in fact be an optimum point of inflection. While nonsignificant, their findings showed that salespeople age 25-34 indicated higher levels of professional commitment than salespeople below 24 or older than 35. Thus, depending on how the previously discussed articles defined, measured and reported their outcomes based on age, an inverse u-shaped relationship may be masked within the data points.

Education: The relationship between education and commitment within the sales force is repeatedly hypothesized as a negative relationship (Bashaw &

Grant 1994; Sager & Johnston 1989; Huddleston

Northern Illinois University et al. 2002). The negative relationship is potentially driven by resulting higher expectations the individual places upon the organization (Mowday et al, 1982) or increased opportunities for mobility (Sager &

Johnston 1989).

In addition to the consistency of the hypothesized relationship, the results also tend to be significant and in the proposed direction

(Sager & Johnston 1989; Bashaw & Grant

1994; Huddleston et al. 2002). These consistent results occur across a variety of samples, including Russian retail sales workers

(Huddleston et al. 2002), a cross-national sample of salespeople within the electronics industry in the United States and Japan (Sager

& Johnston 1989), and a diverse collection of ages and companies of industrial salespeople

(Bashaw & Grant 1994).

Additional Factors: A number of additional variables have been studied in relation to salesperson commitment, including: marital status (Bashaw & Grant 1994), family income

(Bashaw & Grant 1994), tenure (Bashaw &

Grant 1994; Russ & McNeilly 1995;

Huddleston et al. 2002), need for achievement

(Amyx & Alford 2005), Type A vs. Type B personality (Amyx & Alford 2005), motivation

(Ingram et al. 1989), and value domains

(Dubinsky et al. 1997). While results all pertain to the overarching categories of personal characteristics and commitment, there is not sufficient literature studying these specific variables within the sales organization context to form a comparative analysis.

Managerial Implications and Future

Research Directions

This review synthesizes empirically tested relationships which should be considered when attempting to understand or influence a salesperson’s organizational commitment.

Further, we confirm that a number of antecedents play a role in driving salesperson commitment, while also recognizing that in

Academic Article Winter 2009 35 reality a sales manager does not always have the capabilities of influencing each factor to reach maximum commitment. This review represents not only a summary of past research findings, but a foundation for future research.

Specifically covered are the relative relationships between commitment and the antecedent groupings of (1) supervisor characteristics, (2) sales organization characteristics, (3) sales task characteristics and

(4) personal characteristics. As specified, there is a general lack of consistency in regard to the means in which organizational commitment has been defined, operationalized and studied, thus leading to an incomplete understanding of the antecedent conditions of salesperson commitment. The inconsistency of the predictors of organizational commitment is particularly salient amongst categorical personal characteristics . Thus, it is recommended that sales managers direct their efforts on organizational based predictors for two primary reasons: (1) organizational variables

(e.g., supervisor relationships, salesperson characteristics.

The results presented in this review indicate that sales managers should focus on three specific mechanisms in order to best predict salesperson organizational commitment: (1) supervisor relationships, (2) sales organization characteristics and (3) sales task characteristics.

These categories are deemed the strongest primarily because they indicated the least amount of variance in their results across the numerous studies reviewed for this manuscript; as well as their higher degree of the direct control by the organization. sales organization characteristics and sales task characteristics) appear to be more consistent predictors of sales person commitment than personal characteristics, and (2) organizational characteristics are under a higher degree of firm control than manipulating and altering

Table 2. Actions to Enhance Organizational Commitment of Sales Representatives

Supervisor Relationships

Build Trust though…

Improve Communication using…

Adapt a Leadership Style in which…

Sales Manager Procedural Justice (i.e., Having the Same Rules for Everyone)

Reliable Sales Manager Communication

Frequent Two-Way Communications the Sales Manager Clarifies the Expectations of the Salesperson and Shows

Consideration

Sales Organization Characteristics

Equal Pay Levels and Latitude for the Salespeople (i.e., No Favorites)

Improve Perceived Fairness through…

Impartial Higher-Order Treatment of Salespeople (e.g., Promotion Fairness,

Recognition Fairness and Incentives Equity)

Sales Organization Distributive Justice (i.e., Fair Distribution)

Hold All Organization to Higher Ethical Standards (e.g., Promotions Equity)

Enhance Ethical Climate through… Perceived Effort to Improve Organizational Ethics

Sales Task Characteristics

Reducing Internal Role Ambiguity (e.g., Clear Boss Demands)

Lower Role Stress through…

Increase Job Satisfaction by…

Making Sure that Expectations are not in Conflict with each other, while also Making the Tasks Clear, Promoting Job Satisfaction or Increasing Salesperson Decision Making Autonomy

Enhancing Intrinsic Job Rewards

Enhancing Extrinsic Job Rewards for Early Career Sales Personnel, High

Performing Sales Personnel, or Full Commission Sales Personnel

Vol. 9, No. 1

36 Journal of Selling & Major Account Management

Specific to these drivers of salesperson commitment, supervisor relationships foster trust, effective lines of communication and guiding leadership, which in turn consistently enhance the salesperson’s commitment.

Organizations which properly align their goals and performance objectives with that of the salesperson will enhance salesperson welfare and commitment. The alignment of organization and salesperson is accomplished through drivers such as organizational fairness and ethical climate. The sales task can also be designed in such a way as to promote organizational commitment; creating jobs with greater clarity, less conflict and more variety, thus building job satisfaction and commitment. Table 2 summarizes the mechanisms within supervisor relationships, organizational climate and job design, which managers can most consistently use to increase the organizational commitment of sales representatives.

Based on past findings, sales managers should be hesitant to rely on heuristics based on a salesperson’s personal characteristics as an indication of potential organizational commitment. Based on the relatively inconsistent findings in regard to most of the personal characteristics, a direct relationship with salesperson commitment is less likely to exist across numerous sales settings or organizations. However, it appears that as researchers move away from categorical personal characteristics (e.g., gender and age) and toward traits which are representative of the abilities of an individual (e.g., education), the consistency of the results is improved.

Examples of how the research context can moderate the various relationships with organizational commitment have been are identified in this review. For example, across a number of the categorical drivers of organizational commitment, multiple researchers noted moderated or even U-shaped relationships between the independent and dependent variable when personal characteristics

Northern Illinois University such as age, experience or gender were used as moderators (e.g., Dubinsky & Mattson 1979; McColl-

Kennedy & Anderson 2005).

Researchers have discovered that a potential cause of previously cited inconclusive findings was that many independent variables themselves are not unidimensional, but rather a multidimensional construct with potentially differing effects; such as intrinsic and extrinsic job satisfaction and internal and external job ambiguity (Rhoads et al. 1994; Yilmaz 2002).

Based on the findings outlined in this manuscript, future researchers and practitioners should be sure to factor the personal conditions of the research sample, as well as question the unidimensionality of particular independent variables to fully understand the drivers of commitment.

In addition to identifying contexts in which the current relationships may need additional investigation, a number of factors need to be further studied as potential organizational commitment drivers. These represent variables which lacked the necessary depth or frequency of published research needed in order to compare results across varying contextual scenarios and were generally recognized in the

Additional Factors sections of the manuscript.

Finally, the following are important measurement issues in the sales force organizational commitment domain which should be addressed in future research:

• The majority of the studies reviewed were cross-sectional. Longitudinal research may be able to tease apart empirical grounds of issues pertaining to causal ordering of effect, or provide a larger range of independent variables of interest to fully test hypothesized U-shaped or inverted Ushaped relationships. This may explain why some non-linear relationships appear to be theoretically tenable, but the empirical work in organizational commitment does not always capture the relationship. Additionally, experimentation is an avenue for future extensions.

Academic Article

• A validation of the various organizational commitment scales across various salesforce contexts is needed. The nature of the various scales which lends one to be used more than the others, nor the implications of using one scale over the others, is fully understood. Finally, the pros and cons of defining commitment as behavior versus commitment as an attitude still needs to be answered.

Scott B. Friend College of Business

Administration University of Nebraska-

Lincoln

Danny N. Bellenger . Mack Robinson College of Business Georgia State University

James S. Boles J. Mack Robinson College of

Business Georgia State University

REFERENCES

Agarwal, S 1993, ‘Influence of formalization on role stress, organizational commitment, and work alienation of salespersons: a crossnational comparative study’, Journal of

International Business Studies , vol.24, no.4, pp.715-739.

Allen, NJ & Meyer, JP 1990, ‘The measurement and antecedents of affective continuance and normative commitment to the organization’,

Journal of Occupational Psychology , vol.63, no.1, pp.1-18.

Amyx, D & Alford, BL 2005, ‘The effects of salesperson need for achievement and sales manager leader reward behavior’, Journal of

Personal Selling & Sales Management , vol.25, no.4, pp.345-359.

Angle, H & Perry JL 1983, ‘Organizational commitment: individual and organizational influences’, Work and Occupations , vol.10, no.2, pp.123-146.

Babin, BJ, Boles, JS & Robin DP 2000,

‘Representing the perceived ethical work climate among marketing employees’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science , vol.28, no.3, pp.345-358.

Winter 2009 37

Barksdale Jr., HC, Bellenger, DN, Boles, JS &

Brashear, TG 2003, ‘The impact of realistic job previews and perceptions of training on sales force performance and continuance commitment: a longitudinal test’, Journal of

Personal Selling & Sales Management , vol.26, no.3, pp.125-138.

Barnes, JW, Jackson, DW, Hutt, MD & Kumar,

A 2006, ‘The role of culture strength in shaping sales force outcomes’, Journal of

Personal Selling & Sales Management , vol.26, no.3, pp.255-270

Bashaw, ER & Grant, KS 1994, ‘Exploring distinctive nature of work commitments: their relationships with personal characteristics, job performance, and propensity to leave’, Journal of Personal Selling

& Sales Management , vol.14, no.2, pp.41-56.

Behrman, DN & Perreault, WD 1984, ‘A role stress model of the performance and satisfaction of industrial salespersons’, Journal of Marketing , vol.48, no.4, pp.9-21.

Bendapudi, N & Leone, RP 2002, ‘Managing business-to-business customer relationships following key contact employee turnover in a vendor firm’, Journal of Marketing , vol.66, no.2, pp.83-101.

Boshoff, C & Mels, G 1995, ‘A causal model to evaluate the relationships among supervision, role stress, organizational commitment and internal service quality’,

European Journal of Marketing , vol.29, no.2, pp.23-42.

Boyle, BA 1997, ‘A multi-dimensional perspective on salesperson commitment’,

Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing , vol.12, no.6, pp.354-367.

Brashear, TG, Bellenger, DN, Boles, JS &

Barksdale Jr., HC 2006, ‘An exploratory study of the relative effectiveness of different types of sales force mentors’,

Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management , vol.26, no.1, pp.7-18.

Vol. 9, No. 1

38 Journal of Selling & Major Account Management

Brashear, TG, Boles, JS, Bellenger, DN &

Brooks, CM 2003, ‘An empirical test of trust

-building processes and outcomes in sales manager--salesperson relationships’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science , vol.31, no.2, pp.189-200.

Brown, SP & Peterson, RA 1993, ‘Antecedents and consequences of salesperson job satisfaction: meta-analysis and assessment of causal effects’, Journal of Marketing Research

(JMR) , vol.30, no.1, pp.63-77.

Buchanan, B 1974, ‘Building organizational commitment: the socialization of managers in work organizations’, Administrative Science

Quarterly , vol.19, no.4, pp.533-546.

Busch, P & Bush, RF 1978, ‘Women contrasted to men in the industrial salesforce: job satisfaction, values, role clarity, performance, and propensity to leave’, Journal of Marketing

Research (JMR) , vol.15, no.3, pp.438-448.

Chonko, LB 1986, ‘Organizational commitment in the sales force’, Journal of Personal Selling &

Sales Management , vol.6, no.3, pp.19-27.

Chu-Mei, L 2007, ‘The early employment influences of sales representatives on the development of organizational commitment’,

Employee Relations , vol.29, no.1, pp.5-15.

Cook, J & Wall, T 1980, ‘New work attitude measures of trust, organizational commitment and personal need nonfulfillment’, Journal of Occupational Psychology, vol.53, no.1, pp.39-52.

Cron, WL 1984, ‘Industrial salesperson development: a career stages perspective’, Journal of

Marketing , vol.48, no.4, pp.41-52.

Cron, WL & Slocum Jr., JW 1986, ‘The influence of career stages on salespeople’s job attitudes work perceptions, and performance’, Journal of Marketing Research (JMR) , vol.23, no.2, pp.119-129.

Donnelly Jr., JH & Ivancevich, JM 1975, ‘Role clarity and salesmen’, Journal of Marketing , vol.39, no.1, pp.71-74.

Dubinsky, AJ, Howell, RD, Ingram, TN &

Bellenger, DN 1986, ‘Salesforce socialization’, Journal of Marketing , vol.50, no.4, pp.192-207.

Dubinsky, AJ, Jolson, MA, Michaels, RE,

Kotabe, M & Lim, CU 1993, ‘Perceptions of motivational components: salesmen and saleswomen revisited’, The Journal of Personal

Selling & Sales Management , vol.13, no.4, pp.25-37.

Dubinsky, AJ, Kotabe, M & Chae Un, L 1993,

‘Effects of organizational fairness on

Japanese sales personnel’, Journal of

International Marketing , vol.1, no.4, pp.5-24.

Johlke, MC, Duhan, DF, Howell, RD & Wilkes,

RW 2000, ‘An integrated model of sales managers’ communication practices’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science , vol.28, no.2, pp.263-277.

Johnston, MW, Parasuraman, A, Furell, CM &

Black, WC 1990, ‘A longitudinal assessment of the impact of selected organizational influences on salespeople’s organizational commitment during early employment’,

Journal of Marketing Research (JMR) , vol.27, no.3, pp.333-344.

Kahn, RL, Wolfe, DM, Quinn, RP, Snoek, JD &

Rosenthal, RA 1964, Organizational stress ,

John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York.

Katz, D & Kahn, RL 1978, The Social Psychology of

Organization , Wiley, New York.

Koberg, CS & Chusmir, LH 1987, ‘Impact of sex role conflict on job-related attitudes’, Journal of Human Behavior and Learning , vol.4, no.3, pp.51-59.

Lefkowitz, J 1994, ‘Sex-related differences in job attitudes and dispositional variables: now you see them’, Academy of Management Journal , vol.37, no.2, pp.323-349.

Low, GS, Cravens, DW, Grant, K & Moncrief,

WC 2001, ‘Antecedents and consequences of salesperson burnout’, European Journal of

Marketing , vol.35, no.5/6. pp.587-611.

Northern Illinois University

Academic Article

MacKenzie, SB, Podsakoff, PM & Ahearne, M

1998, ‘Some possible antecedents and consequences of in-role and extra-role salesperson performance’, Journal of

Marketing , vol.62, no.3, pp.87-98.

Mathieu, JE & Zajac, DM 1990, ‘A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of organizational…’, vol.108, no.2, pp.171-194.

McColl-Kennedy, JR & Anderson, RD 2005,

‘Subordinate-manager gender combination and perceived leadership style influence on emotions, self-esteem and organizational commitment’, Journal of Business Research , vol.58, no.2, pp.115-125.

McFarlin, DB & Sweeney, PD 1992, ‘Research notes. Distributive and procedural justice as predictors of satisfaction with personal and organizational outcomes’, Academy of

Management Journal , vol.35, no.3, pp.626-637.

McGee, GW & Ford, RC 1987, ‘Two (or more?) dimensions of organizational commitment: reexamination of the affective and continuance commitment scales’, Journal of

Applied Psychology , vol.72, no.4, pp.838-842.

McNeilly, K & Goldsmith, RE 1991, ‘The moderating effects of gender and performance on job satisfaction and intentions to leave in the sales force’, Journal of

Business Research , vol.22, no.3, pp.219-232.

Meyer, JP 1997, ‘Organizational commitment’,

International Review of Industrial and

Organizational Psychology , vol.12, pp.175-228.

Meyer, JP & Allen, NJ 1991, ‘A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment’, Human

Resource Management Review , vol.1, no.1, pp.61-98.

Meyer, JP, Allen, NJ & Smith, CA 1993,

‘Commitment to organizations and occupations: extension and test of a three-component conceptualization’, Journal of Applied

Psychology , vol.78, no.4, pp.538-551.

Winter 2009 39

Moideenkutty, U, Blau, G, Kumar, R &

Nalakath, A 2001, ‘Perceived organizational support as a mediator of the relationship of perceived situational factors to affective organizational commitment’, Applied

Psychology: An International Review , vol.50, no.4, pp.615-634.

Morgan, RM & Hunt, SD 1994, ‘The commitment and trust theory in relationship marketing’, Journal of Marketing , vol.58, no.3, pp.20-38.

Mowday, RT, Steers, RM & Porter, LW 1979,

‘The measurement of organizational commitment’, Journal of Vocational Behavior , vol.14, no.2, pp.224-247.

Mowday, RT, Porter, LW & Steers, RM 1982, Employee organization linkages , Academic Press, San

Francisco.

Palmatier, RW, Scheer, LK & Steenkamp, JB

2007, ‘Customer loyalty to whom? Managing the benefits and risks of salesperson-owned loyalty’, Journal of Marketing Research ( J M R ) , vol.44, no.2, pp.185-199.

Pettijohn, CE, Pettijohn LS & Taylor, AJ 2007,

‘Does salesperson perception of the importance of sales skills improve sales performance, customer orientation, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment, and reduce turnover?’, Journal of Personal

Selling & Sales Management , vol.27, no.1, pp.75-88.

Pierce, JL & Randall, BD 1987, ‘Organizational commitment: pre-employment propensity and initial work experiences’, Journal of

Management , vol.13, no.1, pp.163-178.

Porter, LW, Steers RM, Mowday, RT & Boulian,

PV 1974, ‘Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover among psychiatric technicians’, Journal of Applied Psychology , vol.59, no.5, pp.603-609.

Rhoads, GK, Singh, J & Goodell, PW 1994, ‘The multiple dimensions of role ambiguity and their impact upon psychological and behavioral outcomes of industrial salespeople’, Journal of Personal Selling & Sales

Management , vol.14, no.3, pp.1-24.

Vol. 9, No. 1

40 Journal of Selling & Major Account Management

Roberts, JA & Chonko, LB 1999, ‘The role of perceived equity and justice in managing the modern sales force’, Journal of Marketing

Management ¸vol.9, no.2, pp.84-94.

Roberts, JA & Coulson, KR 1999, ‘Salesperson perceptions of equity and justice and their impact on organizational commitment’,

Journal of Marketing Theory & Practice , vol.7, no.1, pp.1-16.

Russ, FA & McNeilly KM 1995, ‘Links among satisfaction, commitment, and turnover intentions: the moderating effect of experience, gender, and performance’, Journal of Business Research , vol.34, no.1, pp.57-65.

Sager, JK & Johnston, MW 1989, ‘Antecedents and outcomes of organizational commitment: a study of salespeople’, Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management , vol.9, no.1, pp.30-41.

Schaefer, AD & Pettijohn, CE 2006, ‘The relevance of authenticity in personal selling: is genuineness an asset or liability?’, Journal of

Marketing Theory & Practice , vol.14, no.1, pp.25-35.

Schein, EH 1970,

Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Northern Illinois University

Organizational psychology ,

Scholl, RW 1981, ‘Differentiating organizational commitment from expectancy as a motivating force’, Academy of management review , vol.6, no.4, pp.589-599.

Schul, PL & Wren, BM 1992, ‘The emerging role of women in industrial selling: a decade of change’, Journal of Marketing , vol.56, no.3, pp.38-54.

Schwepker Jr., CH 2001, ‘Ethical climate’s relat ions hi p t o job satisfacti on, organizational commitment and turnover intention in the salesforce’, Journal of Business

Research , vol.54, no.1, pp.39-52.

Siguaw, JA & Honeycutt Jr., ED 1995, ‘An examination of gender differences in selling behaviors and job attitudes’, Industrial

Marketing Management , vol.24, no.1, pp.45-52.

Singh, J 1998, ‘Striking a balance in boundaryspanning positions: an investigation of some unconventional influences of role stressors and job characteristics on job outcomes of salespeople’, Journal of Marketing , vol.62, no.3, pp.69-86.

Stafford, EM, Jackson, PR & Banks, MH 1980,

‘Employment, work involvement, and mental health in less qualified young people’,

Journal of Occupational Psychology , vol.53, no.4, pp.291-304.

Steers, RM 1977, ‘Antecedents and outcomes of organizational commitment’, Administrative

Science Quarterly , vol.22, no.1, pp.46-56.

Swan, JE, Futrell, CM & Todd, JT 1978, ‘Same job-different views: women and men in industrial sales’, Journal of Marketing vol.42, no.1, pp.92-100.

Tyagi, PK & Wotruba, TR 1998, ‘Do gender and age really matter in direct selling? An exploratory investigation’, Journal of Marketing

Management , vol.8, no.2, pp.25-36.

Walker, OC, Churchill, GA & Ford, NM 1972,

‘The reactions to role conflict: the case of the industrial salesman’, Journal of Business

Administration , vol.3, pp.25-36

Waters, L 2007, ‘Experiential differences between voluntary and involuntary job redundancy on depression, job-search activity, affective employee outcomes and reemployment quality’, Journal of Occupational

& Organizational Psychology , vol.80, no.2, pp.279-299.

Watson, GW & Papamarcos, SD 2002, ‘Social capital and organizational commitment’,

Journal of Business & Psychology , vol.16, no.4, pp.537-552.

Weeks, WA, Loe, TW, Chonko, LB, Martinez,

CR & Wakefield, K 2006, ‘Cognitive moral development and the impact of perceived organizational ethical climate on the search for sales force excellence: a cross-cultural study’, Journal of Personal Selling & Sales

Management , vol.26, no.2, pp.205-217.

Academic Article

Weeks, WA, Loe, TW, Chonko, LB &

Wakefield, K 2004, ‘The effect of perceived ethical climate on the search for sales force excellence’, Journal of Personal Selling & Sales

Management , vol.24, no.3, pp.199-214.

Wiener, Y 1982, ‘Commitment in organizations: a normative view’, Academy of Management

Review , vol.7, no.3, pp.418-428.

Yilmaz, C 2002, ‘Salesperson performance and job attitudes revisited: an extended model andeffects of potential moderators’, European

Journal of Marketing , vol.36, no.11/12, pp.1389-1414.

Winter 2009 41

Vol. 9, No. 1