Necessity is the Mother of Invention: Why Salesperson

advertisement

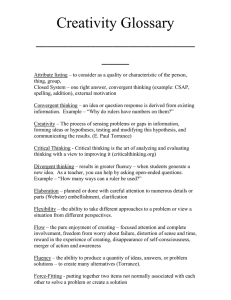

20 Journal of Selling & Major Account Management Necessity is the Mother of Invention: Why Salesperson Creativity is More Important Now than Ever and What We Can Do to Encourage it By David Strutton, Iryna Pentina and Ellen Bolman Pullins The role that creativity may play in facilitating selling success or customer retention has received little attention in the sales or sales management literatures. Yet, given recent changes in the nature of the selling role, creativity may be increasingly important. The act of creation is – or, as reasoned below, absolutely should be – part of the professional salesperson’s job and selling arsenal. Based on the current sales and organizational creativity literatures, we justify, develop and explain a two-stage Sales Creativity Matrix. This matrix introduces five methods through which management might inspire greater ideational creativity among salespeople and five methods through which salespeople might more effectively identify the most useful sales ideas. INTRODUCTION The academic sales and sales management literatures are filled with models explaining what makes salespeople perform more effectively (e.g. Zoltners, Sinha and Lorimer, 2008). Earlier studies focused on personality characteristics and appearance (Lamont and Lundstrom, 1977), adaptive selling capabilities (Weitz, Sujan and Sujan, 1986), and flexibility (Castleberry and Shepherd, 1993). More recently, relationship development skills (Marshall, Goebel and Moncrief, 2003) and the ability to function within a sales team (DeeterSchmelz and Ramsey, 1995) have been identified as key success factors. However, the role of a salesperson’s or a sales team’s creativity has been largely ignored (Wang and Netemeyer, 2004). This is especially troubling since today’s world of selling has been radically reshaped by increased global competition, cutting-edge sales technologies, rapid empowerment of buyers and fragmentation of markets (Moncrief and Marshall, 2005). Such new Northern Illinois University approaches as relationship selling, valueadded and consultative selling are critical to sales function-based competitive advantage in an increasingly commoditized business world, and require sufficient strategic planning that can benefit greatly if sales agents and teams exhibit more creative approaches at each step of the selling process (Piercy and Lane, 2005). The role of creativity in enhancing business processes and functional outcomes has long been recognized. By 1943, Joseph Schumpeter was already writing that capitalism evolves primarily through “creative destruction” that produces, through mutations from within, innovative tech nol ogi es an d orga niz ati on s. Organizational creativity has since been linked to outcomes such as organizational learning (Levinthal and March, 1993), strategic differentiation and sustainable competitive advantage (Porter, 1996), as well as improved new product performance (Im and Workman, 2004), with these relationships becoming stronger in Academic Article turbulent environments characterized by high uncertainty and competiveness (Ford, Sharman and Dean, 2008). The evolution of sales from a marginal activity to a strategic value-creating function responsible for integrating internal departments and customer-facing channels for increased organizational productivity (Geiger and Guenzi, 2009) and competitive differentiation (Piercy and Lane, 2005) logically evokes the need for creativity research in the sales context. Although practitioner-oriented sales literature emphasizes the need for creative, problem-solving sales practices as markets evolve and technology advances (Wang and Netemeyer, 2004), very little attempt has been made to inform best sales practice based on the conceptual, empirical and theoretical literature. To address this gap, the current paper attempts to provide new insights for the practicing managers and salespersons regarding the role of creativity in developing customer solutions and satisfaction, and in securing customer delight and profitable relationships (Zoltner, Sinha and Lonmer, 2008). The remainder of this paper begins with a brief literature review to define creativity and an overview of the state of creativity research as it may relate to professional selling today. It then explores why creativity is so important in selling. Following this, a matrix of the role creativity should be taking in the selling organization is developed that contains pragmatic suggestions for practicing sales managers. LITERATURE REVIEW Creativity has been defined in many ways, such as an individual trait, a cognitive process, a multi -level process, an outcome, a component of problem-solving, and even an organizational outcome. As a cognitive process, for example, Summer 2009 21 Koestler (1964) defined it as a “bisociative process,” the connecting of two previously unrelated matrices of thought to produce a new insight. Alternatively, creativity can be conceptualized as a syndrome with a number of elements including cognitive, personality, and motivational, as well as contextual factors (Mumford & Gustafson, 1988). Ackoff and Vergara (1981) defined it as the ability to break through constraints imposed by habit and tradition so as to find new solutions to problems, strongly connecting it to problemsolving. In sales it has been more connected to the number of new ideas or different behaviors (Wang & Netemeyer, 2004). A summary of some of the key definitions in each area is included in Table 1. For our purposes, it is a process of connecting contextual variables to environmental cues to find new solutions to problems, generate new ideas, and/or perform the sales job uniquely. It is probably worthwhile to consider the role of creativity in problem-solving explicitly. This is a controversial topic, with arguments on both sides: that creativity is a special case of problemsolving and that problem-solving is a special case of creativity. Despite this, most agree that the core processes required for creative problem solving are problem identification and construction, identification of relevant information, generation of new ideas, and the evaluation of these ideas (Basadur, Graen, and Green 1982). Creative problem-solving has three different phases (problem finding, problem solving and solution implementation). In each phase, a two step thinking process of ideation-evaluation occurs. Ideation is the generation of options, different points of view, and perceptions of facts and ideas with out critical judgment. This constitutes the Vol. 9, No. 3 22 Journal of Selling & Major Account Management divergent aspect of the process. On the other hand, evaluation is the judgment and selection of these thoughts. This is the convergence aspect. These are two opposite kinds of thinking skills that are synchronized throughout the process. Given that creativity’s definitions and role in problem-solving are accepted, we then Approach to Creativity Creativity as Individual Trait Creativity as Individual Cognitive Processes Creativity as Multilevel Processes Northern Illinois University need to consider what is known and accepted in the sales literature about creativity. Limited work in the academic sales arena has specifically explored creativity among professional salespeople. Moncrief (1986) concluded that preliminary evidence existed that creativity affects performance. Weilbaker Table 1 Existing Definitions of Creativity Definition References In its narrow sense, creativity refers to the abilities that are most characteristic of creative people. Creativity is a continuous trait in all people; those individuals with recognized creative talents simply have “more of what all of us have” (p.446) People with an innovative problem-solving style approach, consider, solve, and apply problems differently from those with adaptive styles Guilford, J.P. (1950) Insight and productive thinking arise when the thinker grasps the essential features of a problem and their relationships to a final solution Wertheimer, M (1945) Creativity involves “bisociative process” – the connecting of two previously unrelated “matrices of thought” to produce a new insight or invention Koestler, A. (1964) The creative mind is skilled in “lateral” or associative thinking, in which thought can leap from category to category rather than following preexisting paths of cognition de Bono, E. (1991) Creative engagement is a process in which an individual behaviorally, cognitively, and emotionally attempts to produce creative outcomes Kahn, W.A.( 1990) Individual Level: engagement of an individual in a creative act Organizational Level: a process that maps when creative behavior occurs and who engages in creative behavior Drazin, R., M. A. Glynn and R. K. Kazanjian (1999) Individual Creativity: activities undertaken by individual employees within an organization to enhance their capability for developing something which is meaningful and novel within their work environment Organizational Creativity: extent to which the organization has instituted formal approaches and tools, and provided resources to encourage meaningfully novel behavior within the organization Bharadwaj, S. and A. Menon (2000) Kirton, M. (1989) Academic Article Creativity as Outcome Table 1—continued Existing Definitions of Creativity Creative product is anything that produces “effective surprise” in the observer, in addition to a “shock of recognition” that the product or response, although novel, is entirely appropriate A product or response is creative to the extent that appropriate observers independently agree it is creative. Appropriate observers are those familiar with the domain in which the product was created or the response articulated. Thus, creativity can be regarded as the quality of products or responses judged to be creative by appropriate observers, and it can also be regarded as the process by which something so judged is produced. A product or response will be judged as creative to the extent that a) it is both novel and appropriate, useful, correct, or valuable response to the task at hand and b) the task is heuristic (including problem discovery) rather than algorithmic (straightforward) Products, ideas, or procedures that re a) novel or original and b) relevant and useful Creative outcomes are those that are novel and valuable Combined: Internal and External Systems Approach to Creativity Creativity as Organizational Performance Creative ProblemSolving Creativity in sales Componential Approach: Components of creative performance include: a) domain-relevant skills: knowledge, technical skills, talent (cognitive abilities, education) b) creativity-relevant skills: cognitive style, heuristics for generating novel ideas, conducive work style (training, experience, personal traits) c) task motivation: attitudes toward the task, perceptions of own motivation (intrinsic vs. extrinsic interplay) Creativity can be conceptualized as a syndrome with a number of elements: individual cognitive processes, personality, and motivational variables to facilitate application of cognitive processes, and contextual variables such as climate, evaluation, and culture. Any creative idea is affected by three main shaping forces: the field (social institutions selecting the ideas to pursue), the domain (knowledge base and culture disseminating new ideas), and the individual (bringing about creative change). Organizational creativity means deliberately changing procedures to make new, superior levels of quality, quantity, cost, and customer satisfaction possible Creativity is the generation of a valuable, useful new product, service, idea, procedure, or process by individuals working together in a complex social system Summer 2009 23 Bruner, J. (1962) Amabile, T. (1982) Amabile, T. (1983) Oldham, G. and A. Cummings (1996) Ford, C. M. (1996) Amabile, T. (1983) Mumford, M.D. and S.B. Gustafson (1988) Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1988) Basadur, M. and P. A. Hausdorf (1996) Woodman, R. W., J. E. Sawyer and R. W. Griffin (1993) Definition of creativity: ability to break through constraints imposed by habit and tradition so as to find new solutions to problems. Ackoff, R. L. and E. Vergara (1981) Salesperson Creative Performance: the amount of new ideas generated or behaviors exhibited by the salesperson in performing his/her job activities Wang, G. and R. G. Netemeyer (2004) Vol. 9, No. 3 24 Journal of Selling & Major Account Management (1990) explored the cognitive and perceptional selling abilities for missionary salespeople. Creativity was one of nine abilities identified as important by salespeople, sales managers, and their customers. He was particularly concerned with creativity as it relates to how salespeople identify customer needs and innovate the ways to approach customers. In 1997, AtuaheneGima noted that salespeople selling new products require a high level of creativity to facilitate the product launch in the market place. He foun that salespeople with an intuitive problem-solving style are more likely to adopt the new product and better support the selling effort associated with it (Atuahene-Gima, 1997). Perhaps the most focused creativity research in sales has been conducted by Wang and Netemeyer (2004). They proposed that creativity is essential to such tasks as finding new prospects, identifying real needs of a customer, and seeking tailored solutions to customer problems. Their findings supported the notion that customer sales depend on understanding problems and tailoring solutions. When salespeople integrate greater creativity into their sales activities, they may be more likely to provide prospects or customers with innovative, useful and thus more desirable solutions through which their problems can be solved and situations improved (Wang and Netemeyer, 2004). The problem-solving approach to selling that has been accepted for sometime (e.g., Weitz, 1981) relies on the findings that problem-solving increases the likelihood of sales and long-term relationships (Eliashbrg, Lilien and Kim, 1995). As the psychological literature has demonstrated, successful problem-solving is also strongly correlated with creative problemsolving (Amabile, 1998). Today’s salesperson often must coordinate many needs across Northern Illinois University multiple functions in both the buying and selling organization (Plouffe & Barclay, 2007). She or he needs to be able to balance two separate sets of objectives and develop win-win alternative solutions so that both parties are satisfied. This salesperson then becomes an integrator of the two firms, not boundary spanning in the traditional sense (Piercy and Lane, 2005), but serving as a conduit for a seamless system of problem-solving. The ability to identify information or problems and generate alternative solutions becomes very important, escalating the need for creativity. One other clearly relevant generalized change is arising within the sales profession. Market sensing requires that successful salespeople be capable of looking beyond their typical role and day to day operations, and understand what is happening in the external environment that is important to the selling firm, much like creative thinkers must sift and sort multiple levels of information to “sense” out what is relevant to the problem at hand (De Bono, 1993). Also, in the midst of integrating multiple functions, salespeople should be able to both sense relevant information, and develop multiple alternatives that meet a variety of differing criteria if they are to be successful. This requires high levels of creativity that can manifest in various ways. A distinction, for example, is made between ‘real -time’ and ‘multi-stage’ creativity (Drazin, Glynn and Kazanjian, 1999; Ford, 1996). Real-time creativity eventuates - largely spontaneously during the brief time frame in which salespeople operate in the actual presence of customers. By contrast, multi-stage creativity unfolds more deliberately. There, sufficient time exists for more judicious generation, evaluation and selection of creative ideas and approaches Academic Article through which any resulting solutions are presented to customers more creatively. Since the real-time creativity is largely spontaneous and individualized, this paper focuses on the multi-stage creativity that is more amenable to managerial input and training and is consistent with the view of sales as more strategic in planning and value creation (Piercy & Lane, 2005; Geiger & Guenzi, 2009). Imagine a Tier 1 automotive parts manufacturer selling to a Big Three manufacturer. Perhaps this particular salesperson has one purchase agent with a specific model that represents most (or all) of her customer base. She discovers they are revamping the model and has to coordinate her engineering staff with the automotive manufacturer’s product line managers in both organizations. She also needs to bring together finance, training, operations individuals, and others. She must be good at sensing the needs of the remodel, developing various alternatives, creating solutions that will “work” from an engineered perspective, but also create greater value for her customer than does the competitor’s proposal. She also has to create the proposal in such a way that it repositions the original offering in an appealing and persuasive manner. This salesperson is likely relying on multi-stage creativity processes. Of particular note, the expanded time frame should enable salespeople and managers to manage the creative process more strategically and effectively. A second distinction that may be relevant within the sales arena is between the two distinct categories of divergent and convergent thinking (Woodman et al., 1993). Divergent thinking encompasses the intellectual predilection and applicable abilities of salespeople to create (i.e., originate) numerous inventive, fully-elaborated Summer 2009 25 and diverse ideas. Convergent thinking encompasses the intellectual discipline and applicable abilities of salespeople to rationally evaluate, critique and identify those best ideas from any batch created during the divergent creative stage (Woodman et al., 1993). Divergent thinking appears essential to ensuring the novelty and appeal of creative sales solutions. Yet as a necessarily complementary factor, convergent thinking may be every bit as essential as a means to ensure the appropriateness and practical suitability of any ideas selected for pursuit. This harks back to the idea of the two types of thinking aligning in creative problemsolving discussed earlier. It makes sense for sales as it is an iterative process with clear decision making stages. In addition, one practical approach to the sales process, Conceptual Selling (Miller & Heiman 2005) –explicitly deals with these concepts, divergent and convergent thinking, as an important constructing the practice of personal selling. While few sales professionals are likely to innately possess the intellectual, functional or temporal prerequisites necessary to engage naturally and optimally in divergent and convergent creativity, purposive management of the creative processes could ensure that most sales professionals develop the necessary creativity-related skill sets (Epstein, Schmidt and Warfel, 2008). While managers could be more or less creative in their own thoughts and activities, their role is critical insofar as they influence the performance of salespeople who report to them (Deeter-Schemltz, Goebal and Kennedy, 2008). Additionally, sales managers could consciously lead or execute through methods and approaches that facilitate or inspire greater original ideation and more creative selection processes amongst members of their sales Vol. 9, No. 3 26 Journal of Selling & Major Account Management forces. managerial implications are derived. MULTI-LEVEL SALES CREATIVITY MATRIX AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR MANAGERS Methods for Stimulating Idea Generation: Divergent Thinking Proposition 1: Sales Managers who construct intersections will improve idea generation for themselves and their sales forces. By combining the concepts of divergent and convergent thinking processes at both the sales manager and salesperson level, Figure 1 depicts the Multi-Level Sales Creativity Matrix that results when the two relevant organizational creativity levels and creativity processes are combined in a unifying scheme. The figure demonstrates sales manager specific examples of both divergent (idea generation) aspects of creativity important to the sales manager’s job, as well as convergent (idea evaluation) aspects. It also shows the salesperson convergent and divergent applications of creativity. Finally, management interaction creativity, which may have components of both convergent and divergent thinking are also identified. Based on the Matrix (Figure 1) and the extant creativity literature, in the discussion that follows a number of broad propositions and specific One strategy for sales managers to encourage creative idea generation might be to deliberately create teams that force intersections between individuals with different perspectives to offer. This strategy involves the formation of managed intersections between sales team members or salespeople and their managers. Amabile (1988, 1998) conceived such intersections as interactive, iterative processes where individuals develop ideas, present each to the group, work further in solitude on successfully vetted issues and then return to the group to further modify and polish surviving ideas. Managed intersections could be devised either to identify unique customer problems or to create new-to-world customer solutions. Such intersections can be established through a two- Divergent Figure 1: Sales Creativity Matrix Sales Manager Salesperson 1. Construct intersection 3. Acknowledge Barriers to Creativity 2. Create Diverse Cross-Functional Teams 4. Shun Conventional Wisdom 5. Engage in Desirable Leadership Behaviors Convergent 6. Integrate Creativity Metrics Sales Manager Salesperson 7. Defer Judgment 9. Answer go-no go questions 8. Assemble Diverse Evaluation Teams Northern Illinois University 10. Assess Idea Risk Academic Article stage process. In the first, leadership could evaluate and classify the entire set of prior experiences and relative hard (i.e., analytical) and soft (i.e., emotional, as in ‘emotional IQ’) strengths that their individual sales reports bring to their job. Likely, individuals who collectively make-up any moderately to large-sized sales unit have emerged from diverse backgrounds, and feature different relative strengths and weaknesses. Cases where this strategy is currently used in practice include weekly sales meetings. One business services firm has a Friday morning meeting every single week. Salespeople are encouraged to share accounts they are struggling with and brainstorming occurs. The salespeople are asked to think about the alternatives generated and to discuss them again at the next meeting. Where possible, teams like this can be assembled deliberately, with the end-goal of maximizing the entire unit’s creativity. Still untapped, yet highly creative, sales ideas surely exist. By strategically facilitating such ‘intersectional exchanges’ of best-practice selling concepts or customer experiences, managers might uncover more creative ideas. Greater numbers of original ideas and, ultimately, creatively useful customer solutions, would almost surely follow. Proposition 2: Sales Managers who create crossfunctional teams will enhance the idea generation of their sales force. Strategically introducing ‘outsiders’ into customer evaluation and sales ideation or presentation processes, and honoring their divergent perspectives, for example, can promote intersectional creativity effects. To illustrate, dependent on the challenges and circumstances being encountered, management might embed cost-oriented production or Summer 2009 27 financial experts with a salesperson or within a selling team. Consistent with Peter and Donnelly’s position (2002), an embedded individual’s divergent, i.e., cross-functional, experiences could ignite intersectional effects that stimulate more original thinking among sales professionals. In one author’s experience, an industrial manufacturer required that headquarters management personnel ride along with salespeople on a fairly regular basis. The first goal of this program was that the HQ managers be exposed to the “real world” and its customers. However, an interesting side effect that arose was that the HQ managers often brought a unique perspective to the field salesperson. On numerous occasions salespeople would end up complimenting the ride-alongs on unique insights or innovative solutions that they brought up. Fashioning and honoring such an official outsider sales role, even periodically, could keep new questions and issues arising and intersectional perspectives surfacing when salespeople or selling teams encounter new or existing customer challenges. If actual ride-alongs, or additional sales team members aren’t viable, other methods exist through which management might promote powerful intersectional-stimulating and associative barrier-dampening effects. Their sales reports, for example, could be required to purposefully adopt, inside their minds, perspectives that otherwise would have to be introduced from outside sources. Specifically focused training or continuing education sessions could facilitate this exact result. What sorts of original insights might be inspired if salespeople were required to identify, critically evaluate and resolve emergent customer problems from wholly open-minded Vol. 9, No. 3 28 Journal of Selling & Major Account Management perspectives? Proposition 3: Salespeople who acknowledge barriers to creativity will improve their idea generation. Extremely creative salespeople might frequently encounter the need to overcome the opposition of others, such as sales managers or senior associates, who rather reflexively reject original ideas. Yet, the biggest obstacles to accepting and originating truly creative ideas most salespeople will encounter exist inside their own minds. Johannson (2005) defined these persistent, naturally-arising, deeply-internalized obstacles as ‘associative barriers.’ Associative barriers can act like super-glue affixed to the wheels of otherwise creative progress. Their presence promotes friction, inside all our minds, friction that impedes and inhibits otherwise more naturally-arising creative instincts, abilities and activities of anyone dragged down by them. Even in collaborative, mutually supportive and respectful sales manager-salesperson relationships, associative barriers could emerge readily from connections that sales managers or experienced salespeople have already established with their profession’s or market’s established ideas, principles, processes or methods. Logic dictates that the ‘better informed’ sales managers are, or the more that experienced salespeople ‘learn about how things ought to be done (around here),’ the more likely it is that either group will be weighed down by associative barriers. Creative disadvantages may well characterize selling firms whose managers did not encourage salespeople to lower their associative barriers when seeking creativity, and reward them for succeeding. Both managers and salespeople should be trained to recognize associate barriers, and cautioned to not buy-in to the status quo or Northern Illinois University the “way we’ve always done it.” In addition, rewards can be generated that recognize original idea generation so that the tendency to bury anything too different may be overcome. Proposition 4: Salespeople that shun conventional wisdom will improve their idea generation. Following precedent often makes sense. Conventional thinking is unlikely to become precedent unless it worked in the past. But things can change. And in myriad modern sales environments, many things are changing. In such situations, excessive adherence to conventional thinking might prove an unfortunate framework for evaluating the suitability of original ideas. One example of this attachment to conventional wisdom comes to us from a risk management firm that made a commitment to update their processes and focus on relationship development. The investment was made in thorough retraining and several national kick off meetings. Yet, six months later the business development manager reports that many of the more experienced yet more moderately successful salespeople insist on holding on to the traditional techniques that aren’t working but that they “know” work for them. Salespeople can be encouraged to think out of the box. Creativity training can be valuable and show that it is valued in the sales team’s environment. Salespeople can be challenged by goals and incentives to develop more new ideas. Sales meetings can dedicate time to generating new ideas to typical problems. These practices are often used in some of the best sales forces and can be adapted to help salespeople to look at doing things other than according toconventional wisdom. Academic Article Methods for Managing for Improved Creative Ideation and Evaluation Proposition 5: Sales Managers who engage in desirable leadership behaviors will encourage both more idea generation and better idea evaluation among their salespeople. Sales managers can be mindful to reward creativity in their sales force. Few desirable workplace behaviors arrive completely independent from effective managerial leadership behaviors (Deeter-Schmelz et al., 2008). Managers should materially, equitably and visibly reward creative ideas or solutions. Specifically, the tactic entails a conscious managerial decision to display leadership signals reflecting confidence that creative approaches exist through which current customer challenges or market opportunities can be resolved. But those same behaviors should be devoid of any dogma regarding how the salespeople who report to such managers might achieve the designated creative task. If their managers displayed such behaviors, salespersons might logically conclude that opportunity exists for them to be self-starting, fully engaged, and more creative (Langer, 1989). While any feedback provided to their salespeople could stimulate idea generation efforts, the actual process of attempting to answer questions should also facilitate more creative managerial insights, as well. New questions often stimulate new perspectives. These new perspectives provide substantial information and interpretation to manager ‘respondents.’ If managers extend themselves just a bit, by asking questions of the salespeople, both groups should grow more creative. When managers make it clear they accept occasional deviation from routine selling methods, more naturally creative salespeople seem more likely Summer 2009 29 to step up, create and contribute. In this regard, managers probably should encourage more than incremental improvements in the creative solutions developed by their salespeople and should clearly model creative problem-solving for their salespeople. Proposition 6: Sales Mangers that integrate creativity metrics will encourage both more idea generation and better idea evaluation among their salespeople. Given the “ambiguity” surrounding creativity, managers may steer away from establishing clear metrics for idea generation and evaluation among their salespeople, but this need not be the case. For the sales manager that establishes clear and measurable creativity goals, and actually measures creative performance, increases in both creative idea generation and quality of creative solutions should follow, bringing along the rewards. Because creativity is not always well defined or understood in the sales force, managers should probably work closely with their salespeople in establishing metrics. Firms can also encourage sharing creative approaches and the rewards they generated across divisions or regions. When open conversation about the importance and value of creative ideation and evaluation occur, and then metrics are set, and measured, improvement in overall selling creativity should be expected. As creativity becomes a rewarded behavior, sales managers must make sure to also acknowledge failure and make sure that salespeople are prepared to learn from it. Sales personnel who are capable of creativity will also understand that those who generate more ideas would experience more failures. This simple relationship should be publicly acknowledged by management. Management should encourage salespeople to learn from their creative failures, Vol. 9, No. 3 30 Journal of Selling & Major Account Management and upgrade processes and outcomes as a result. Management should likewise emphasize that making occasional mistakes by expanding their creative vision is acceptable, but that repeating the same mistake is not. False steps, and occasional mistakes, are necessary to lower associative barriers, stimulate intersectional thinking, create and blend new perspectives, and ultimately, generate new ideas. Over the longer term, the best solutions result from the most stretched imaginations (Cummings and O’Connell, 1978). Methods for Ensuring Effective Evaluation: Convergent Thinking Idea Proposition 7: Sales Managers who defer judgment will improve idea evaluation by their sales force. Sales Managers should avoid hurried judgments of any creative ideas or solutions developed by their sales force. Deferring judgments can prove emotionally challenging for many sales managers, as highly qualified managers’ minds tend to judge quickly because they already enjoy deeply rooted field sales expertise. Yet, by judging too hastily, the risk of automatically discarding genuinely original ideas by comparing them to solutions already known to work expands significantly. Thus at this stage creative minds should judge original ideas leisurely to the extent possible. This is especially true in modern markets where customer demands or competitive initiatives can change so rapidly. Ideally, the sales manager would always have the leisure to consider but this is not viable. While sometimes quick decision-making is needed, it is never too late to revisit a new strategy which may have value in other situations. Proposition 8: Sales Managers who exploit naturallyarising inequities will improve idea evaluation in their sales force. Northern Illinois University The composition of any evaluating team employed during this process probably matters greatly. In any unit, some people excel at divergent – or original - thinking. Others may be better at critically evaluating ideas. Likely, few could truthfully claim mastery over each skill set. Thus certain inequities probably exist within most moderate sized or larger sales forces. That ‘diversity’ is subject to exploitation. And for creativity evaluation purposes, it should be. When assembled, creativity identification teams should be constructed such that more robust divergent thinkers complement stronger convergent thinkers. Then, when charging any evaluative team with the task of identifying the most effective ideas or sales solutions, management would not have to encourage team members to blend their diverse perspectives in arriving at their best choice. Instead, the assorted identification team members would naturally do it themselves. By exploiting evaluative team inequities, evaluative team combinations featuring diverse thinkers will yield the best outcomes (Pinto, Pinto and Prescott, 1993). Proposition 9: Salespeople who answer “Go-No Go” questions will improve their idea evaluation. As idea generation increases, the salespeople themselves need tools to help them with idea evaluation. Following are some sample questions that can be shared with salespeople to the various ideas that they are generating for any given customer problem/ selling scenario. Each question should be answered with respect to each original sales idea created during the initial creativity process. Responses should be compared for each now-competing idea. As each idea is being evaluated, the salesperson should remain vigilant of any unique environmental circumstances, competitive Academic Article challenges or customer opportunities that their firm is currently confronting. Such questions might include: • Were this specific sales idea pursued by our firm, and purchased by the focal customer or customer firm, would execution requirements mesh with our firm’s existing or potential capabilities? • Would successful execution of this specific idea fulfill the exact purposes for which it is intended with respect to both our firm and the customer firm? • If the firm acts based on this idea, would it be pursuing more creative endeavors than can be effectively managed? • Would focal salespeople be able to believe with their hearts and minds in the value of the customer solution? Assuming the idea is presented effectively, is it reasonable to believe focal customers could be educated so that they eventually discern the unique value of the solution? No matter how seemingly attractive original sales ideas (solutions) are generated during the idea generation process, the prospect of ultimate sales failure will increase markedly unless the ideas identified by the firm for actual execution fit with existing production, marketing or customer constraints. Nor should ‘successful’ ideas ever require a selling firm to acquire new, enabling resource advantages at too high a cost (Crawford and DiBenedetto, 2006). Clearly, answering each question affirmatively, in the order presented, might lessen the likelihood that a deficient creative sales solution is selected. Directly answering each question should pointedly require evaluators to visualize how and whether each idea being evaluated could be Summer 2009 31 integrated into a sales approach, and executed successfully. Customization of the questions, to account for unique constraints that might be encountered in particular selling situations, is also clearly possible. Proposition 10: Salespeople who assess idea risk will improve their idea evaluation. Salespeople need to evaluate risk for the ideas that they generate. Even when each question is answered positively for an idea, final choices will still be accompanied by various types of unmitigated risk. (These risks include the risk of choosing nothing at all.) Thus the risks associated with vetting ideas still surviving at this point should themselves be evaluated from a psychological perspective that increases the prospect that the true ‘best’ original sales idea is selected – despite its risk. To achieve this result, salespeople should evaluate the risks associated with actually choosing any still competing idea from a properly balanced risk perspective. Perhaps the key precondition for continued success at this point of the identification process is mindful avoidance of certain highly predictable psychological traps. Because such ‘traps’ are predictable, they are generally manageable. By avoiding these traps, sales professionals will have attained a more balanced view of risk. Such a balanced risk perspective can prove crucial, insofar as successfully managed risk and genuine creativity are likely to rise or fall in concert. Absent a proper risk perspective, otherwise original ideas could be eliminated from further consideration because they were wrongly deemed too risky. Unique choices, such as any decision to choose and pursue a boldly innovative sales idea, may generate, at the outset, unique consequences. To account for this predictable phenomenon, the key consequences that would likely ensue from Vol. 9, No. 3 32 Journal of Selling & Major Account Management both the sales firm’s and focal customer’s perspective if each of the creative sales ideas still in play after the go/no go question have been answered should be mapped out. For instance, a salesperson could estimate the negative or positive values associative with the outcomes presumed to be associated with implementing each sales idea, as well as the probability that each outcome would occur. David Strutton Professor of Marketing Director, New Product Development Scholars Program P.O. Box 311396 University of North Texas Denton, TX 76203-1396 Strutton@unt.edu SUMMARY Creativity does not come easily or naturally to many people, and the best approach to ideabased creative selling would likely be different on a firm-by-firm and customer-by-customer basis. No one-size-fits-all creative customer solution could ever exist. But these facts do nothing to degrade the lasting, universal value, of creative selling, and the need to pursue and exercise it properly. Based on modern empirical evidence and historically-verified creative approaches, the Sales Creativity Matrix may facilitate additional, more effectual and more effectively managed sales creativity within sales organizations. It can facilitate ‘divergent’ creative activities within sales units, and allow those same units to engage more effectively in ‘convergent’ creative activities. These ‘divergent’ activities should promote the generation of greater numbers of creative ideas within any sales unit. In turn, the ‘convergent’ activities should facilitate the identification of the best/ most useful ideas from amongst any batch stimulated as a result of the divergent process. Iryna Pentina Assistant Professor of Marketing University of Toledo 2801 W. Bancroft St., MS 103 Toledo, Ohio 43606 ipentin@utnet.utoledo.edu Ellen Bolman Pullins Professor of Marketing Schmidt Research Professor of Sales & Sales Management University of Toledo 2801 W. Bancroft St., MS 103 Toledo, Ohio 43606 Ellen.pullins@utoledo.edu REFERENCES Ackoff, Russel L. and Elsa Vergara (1981), “Creativity in Problem-Solving and Planning: A Review,” European Journal of Operational Research, 7, pp. 1-13 Amabile, T. M. (1982), Social Psychology of Creativity: A consensual Assessment technique. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 997-1013. Amabile, T. M. (1983), The Social Psychology of Creativity: A Componential Conceptualization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45 (2), 357-376. Northern Illinois University Academic Article Summer 2009 33 Amabile, T. M. (1988), “A Model of Creativity and Innovation in Organizations,” Research in Organizational Behavior, 10, 23-167. Cummings, L. L. and M. J. O’Connell (1978), “Organizational Innovation,” Journal of Business Research, 6, 33-50. Amabile, T. M. (1998), “How to Kill Creativity,” Harvard Business Review, September-October, 77-87. De Bono, E. (1991), Lateral and vertical thinking. In J. Henry (Ed.), Creative Management, pp. 16-23. London: Sage. Atuahene-Gima, K. (1997), “Adoption of New Products by the Sales Force: The Construct, Research Propositions, and Managerial Implications,” Journal of Product Innovation Management,” 14, 498-514. De Bono, E. (1993), Serious creativity: using the power of lateral thinking to create new ideas. Harper Business, New York. Basadur, Min and Peter A. Hausdorf (1996), “Measuring Divergent Thinking Attitudes related to Creative Problem Solving and Innovation management,” Creativity Research journal, 9 (1), 21-32. Beatty, J. (1998). The World According to Peter Drucker. The Free Press: New York, NY. Bharadwaj, S. and A. Menon (2000), “Making Innovation Happen in Organizations: Individual Creativity Mechanisms, Organizational Creativity Mechanisms or Both?” Journal of Product Innovation Management, 17, 424-434. Bruner, J. (1962), The conditions of Creativity. In Gruber, G. Terrell, and M. Wertheimer (Eds.), Contemporary Approaches to Creative Thinking. New York: Athernon Press. Castleberry, S. B. and C. D. Shepherd (1993), “Effective Interpersonal Listening and Personal Selling,” Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 13 (Winter), 35-49. Crawford, M. & Di Benedetto, A. (2006). New Products Management. McGraw-Hill/Irwin: New York. Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1988), Society, Culture, and Person: A systems view of creativity. In R. G. Sternberg (Ed.). The Nature of Creativity: Contemporary Psychological Perspectives, pp. 325339, New York: Cambridge University Press. Deeter-Schmelz, D. R. and R. Ramsey (1995), “A Conceptualization of the Functions and Roles of Formalized Selling and Buying Teams,” Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 15 (Spring), 47-60. Deeter-Schmelz, D. R., D. J. Goebel, and K. N. Kennedy (2008), “What Are the Characteristics of an Effective Sales Manager? An Exploratory Study Comparing Salesperson and Sales Manager Perspectives,” Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 28 (1), 7-20. DiLiello, T.C. and J.D. Houghton (2008), “Creative Potential and Practised Creativity: Identifying Untapped Creativity in Organizations,” Creativity and Innovation Management, 17 (1), 37-46. Drazin, R., M. A. Glynn and R. K. Kazanjian (1999), “Multilevel Theorizing about Creativity in Organizations: A Sensemaking Perspective,” Academy of Management Review, 24 (2), 286-307. Eliashberg, J., G. Lilien, and N. Kim (1995), “Searching for Generalizations in Business Marketing Negotiations,” Marketing Science, 14 (3), 647-660. Epstein, R., S. M. Schmidt and R. Warfel (2008), “Measuring and Training Creativity Competencies: Validation of a New Test,” Creativity Research Journal,, 20 (1), 7-12. Vol. 9, No. 3 34 Journal of Selling & Major Account Management Ford, C. M. (1996), “A Theory of Individual Creative Action in Multiple Social Domains,” Academy of Management Review, 21, 1112-1142. Ford, C. M., M. P. Sharfman, and James W. Dean (2008), “Factors Associated with Creative Strategic Decisions,” Creativity and Innovation Management, 17 (3), 171-185). Geiger, S. and P. Guenzi (2009), “The Sales Function in the Twenty-First Century: Where Are We and Where Do We Go from Here?” European Journal of Marketing, 43 (7), 873-89. Guilford, J.P.(1950) Creativity. Psychologist, 5, 444-454. American Gurteen, D. (1998), “Knowledge, Creativity and Innovation,” Journal of Knowledge Management, 2 (1), 5-13. Im, S. and J. P. Workman Jr. (2004), “Market Orientation, Creativity, and New Product Performance in High-Technology Firms,” Journal of Marketing, 68, 114-132. Lamont, L. M and W. J. Lundstrom (1977), “Identifying Successful Industrial Salesmen by Personality and Personal Characteristics,” Journal of Marketing Research, 14 (November), 517-529. Langer, E. (1989) Mindfullness. Perseus Book Group: Cambridge, Mass. Levinthal, D.A. and March, J.G. (1993), “The Myopia of Learning,” Strategic Management Journal, 14, 95-112. Marshall, G. W., D. J. Goebel and W. C. Moncrief (2003), “Hiring for Success at the Buyer-Seller Interface,” Journal of Business Research, 56, 247-255. Miller, R. B. and S. E. Heiman (2005), The New Conceptual Selling, Warner Business Books, New York. Moncrief, W. C. (1986). “Selling Activity and Sales Position Taxonomies for Industrial Salesforces,” Journal of Marketing Research, 23 (3), 261-70. Johannson, F. (2005). The Medici Effect. Harvard Business School Press: Boston, Mass. Moncrief, W. C. and G. W. Marshall (2005), “The Evolution of the Seven Steps of Selling,” Industrial Marketing Management, 34, 13-22. Kahn, W.A.( 1990), Psychological Conditions of Personal Engagement and Disengagement at Work, Academy of Management Journal, 33: 692-724. Mumford, M. D. and S. B. Gustafson (1988), “Creativity Syndrome: Integration, Application and Innovation,” Psychological Bulletin, 103, 27-43. Kirton, M. (1989), Adaptors and Innovators: Styles of Creativity and Problem-Solving New York: Routledge. Oldham, G. and A. Cummings (1996), “Employee Creativity: Personal and Contextual Factors at Work,” Academy of Management Journal, 39, 607-634. Koestler, A. (1964), The Act of Creation. New York: Dell. Kurtzberg, T. R. and T. M. Amabile (2001), “From Guilford to Creative Synergy: Opening the Black Box of Team-Level Creativity,” Creativity Research Journal, 13 (3 and 4), 285-294. Northern Illinois University Peter, J. Paul and J. H. Donnelly (2002), Preface to Marketing Management, 9th edition, McGrawHill. Piercy, N. F. and N. Lane (2005). Strategic Imperatives for Transformation in the Conventional Sales Organization. Journal of Change Management, 5(3), 249-266. Academic Article Summer 2009 35 Pinto, M. B., Pinto, J. K. & Prescott, J. E. (1993). Antecedents and Consequences of Project Team Cross-Functional Cooperation. Management Science, 39 (10), 1281-1297. Porter, M. E. (1996), “What is Strategy?” Harvard Business Review, November-December, 61-78. Sutton, R.I. and A. Hargadon (1996), “Brainstorming Groups in Context: Effectiveness in a Product,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 41, 685-718. Wang, G. and R. G. Netemeyer (2004), “Salesperson Creative Performance: Conceptualization, Measurement, and Nomological Validity,” Journal of Business Research, 57, 805-812. Weilbaker, D. C. (1990), “The Identification of Selling Abilities Needed for Missionary Type Sales,” Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, X, 45-58. Weitz, B. A. (1981), “Effectiveness in Sales Interactions: A Contingency Framework,” Journal of Marketing, 45 (1), 85-103. Weitz, B. A., H. Sujan, and M. Sujan (1986), “Knowledge, Motivation, and Adaptive Behavior: A Framework fro Improving Selling Effectiveness,” Journal of Marketing, 50 (October), 174-191. Wertheimer, M. (1945), Productive Thinking. New York: Harper & Row. Woodman, R. W., J. E. Sawyer and R. W. Griffin (1993), “Toward a Theory of Organizational Creativity,” Academy of Management Review, 18 (2), 293-321. Zoltners, A. A., Prabhakant, S., and S. E. Lorimer (2008), “Sales Force Effectiveness: A Framework for Researchers and Practitioners,” Journal of Personal Selling ad Sales Management, 2, 8 (2), 115-131. Vol. 9, No. 3