WP 754-74 November, 1974

advertisement

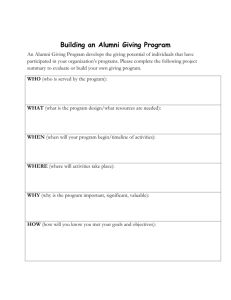

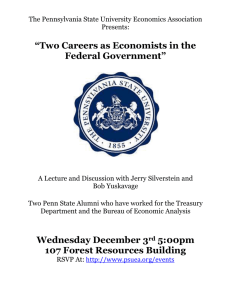

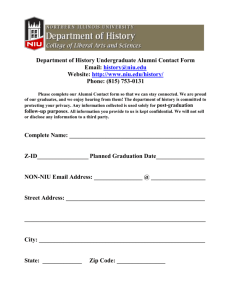

A TAXONOMY OF TECHNICALLY BASED CAREERS* LOTTE BAILYN and EDGAR H. SCHEIN November, 1974 WP 754-74 *From L. Bailyn and E. H. Schein, Work Involvement in Technically Based Careers: A Study of M.I.T Alumni at Mid-Career, (in progress, 1974). _1_^____(__1_____1___11^_11_____1_1 Chapter 2 A Taxonomy of Technically Based Careers When we speak of technically based careers, we are referring to a number of general characteristics of the men in the sample. First, all are graduates of a technological institute in which a core of mathematics and science courses was an absolute undergraduate requirement, even among those who majored in "non-technical" fields. And though some respondents now have jobs seemingly unrelated to their undergraduate major (e.g. a physicist now doing photography), the bulk of the careers under study directly reflect this initial technical training. Second, the decision to come to M.I.T. presumably reflects a particular pattern of talents, motives, and values already present in high school. The desire to be educated in science and technology implies, on the part of a high school graduate, an already existing commitment to a particular range of fields. People who are attracted to the fields of science and engineering have certain personality traits and needs that distinguish them from those who enter the field of humanities. Those in science and engineering show, at an early age, an inclination toward scientific, mechanical, quantitative activities rather than aesthetic ones (Sternberg, 1955; Hudson, 1967). Compared to those in humanities, they are less people-oriented and more thing-oriented--they would rather deal with objects than people (Roe, 1957; Rosenberg, 1957; Perrucci and Gerstl, 1969). Scientists and engineers have a high need for achievement (Dipboye and Anderson, 1961; Izard, 1960) as well as a high need for selfexpression (Rosenberg, 1957; Perrucci and Gerstl, 1969). They are concerned with order and stability (Moore and Levy, 1951; Steiner, 1953; Izard, 1960; Roe, 1961; Perrucci and Gerstl, 1969) and are less flexible than those in humanities. They also differ in their cognitive styles, having been found to be more convergent than divergent (Hudson, 1967; Kolb and Goldman, 1973). ____1_111^·^1_111_·--1111_11__ .11__.. III -2- Though there is no direct evidence of the personality, cognitive style, and values of the respondents when they first entered M.I.T., they most likely fit the scientific pattern, a pattern that would have been further reinforced by their undergraduate curriculum. homogeneous group: staff positions As graduates, therefore, they were a relatively over half (51%) entered the world of work in engineering And though, subsequently, their careers followed a variety of paths, it is important to keep this common base in mind in analyzing their current occupational roles. Occupational Categories--The External Career The process of finding a taxonomy of objectively defined careers went through several stages. The first step was to code the respondents' present occupation into a valid and meaningful set of occupational categories that would reflect the technical bias of the.sample. This meant, for instance, that engineers and scientists were not combined, as is often done in occupational classifications, and that technical managers were kept separate from other functional managers, even though such groups are often combined in surveys of managers. The final set of categories chosen is shown in Table 1. Before looking at the frequencies, it is necessary to explain the meaning of some of these categories, particularly in the area of "management." We wanted to differentiate unambiguously those respondents who were clearly entrepreneurial in their orientation, those who were clearly oriented toward general management per se, and those who were oriented toward a particular business or technical function. We did not want to confuse any of these categories with that of the manager whose job reflects involvement in a family concern, where it would be difficult to judge how much of his 1 A further 12% combine, in their first jobs, engineering with other duties. The figures given are based on the 87% of the respondents for whom information on first jobs is available. -3- performance was the result of his own achievement and how much reflected the initial family position. Nor did we want to confuse first level supervision with management. Given these initial concerns the managerial categories were defined in the following way: 1. Entrepreneurs are those managers who in one way or another are involved in the founding of their own company, regardless of their present rank. That is, some of these men are now presidents, others are technical managers, others are vice-presidents. What is distinctive about them, as evidenced also in other analyses (Roberts and Wainer, 1971; Schein, 1972, 1974) is not their present rank but the fact that they have been involved in entrepreneurial activity. 2. General Managers are men who clearly occupy a position above functional management. These individuals attained their positions through promotion rather than by founding their own company or joining a family business. Sample job titles are president, executive vice-president, general manager, managing director, division president, group-vice-president. 3. one. Functional Managers head a function other than a purely technical For example, vice presidents of finance or personnel directors are functional managers. Some company titles such as secretary, chief counsel, and treasurer were found to be ambiguous--did they belong in the functional or general manager category? In those cases we looked at the entire question- naire and attempted to make a judgment as to which group the man belonged in. Similar analyses were made of a few ambiguous jobs such as vice-president of planning or director of corporate development. 4. Technical Managers are those men who are clearly in charge of a technical function such as basic research or technical sales support. *XS iS0geN research and development, engineering Excluded from this category are first-line technical III -4supervisors, group heads, or team leaders, who described themselves essentially as senior technical people. The individual had to be at least two levels above the working technical level and had to list managerial responsibilities as part of his job. A further subclassification of this category concerned the technical areas involved: engineering, computer applications, and science. Decisions of field were made mainly on the basis of self-description, corroborated, where necessary, by checking back on the undergraduate majors of the respondents. Once the managerial roles were properly defined, the rest ification was simpler. the class- Non-management or staff designations were given to those employees of companies or laboratories who did'not fit the management criteria, and included, therefore, first-level supervisors, team leaders, and project leaders. This group was divided into Technologists, which were further differentiated by technical field, and Business Staff. The latter category includes salesmen, financial analysts, and other functional specialists who are neither in management nor in a purely technical role. The classification of respondents into the Educational and Other categories posed no special problems inasmuch as those categories were straight2 forward and unambiguous. 2 Coding into occupational categories was done by the two authors in conjunction with Dany Siler, research assistant to the project at that time. We used, where necessary, all the items in the questionnaire touching on'the alumni's current occupations, but concentrated mainly on job title and brief description of function. Error was minimized by having at least two of us independently code each questionnaire. In about 95% of the cases (based on a check of one fourth of the questionnaires) the first two coders agreed on their classification, which then became final. If disagreement remained after discussion between the two initial coders, the questionnaire was given to the third person and final classification was based on the consensus of all three researchers. - 5With these definitions in mind let us look at the occupational distribu3 tion presented in Table 1. Initially this information is given separately for each of the three classes in an attempt to identify the differences in distribution of the three age groups. It should be clear, of course, that any such differences that exist may not only be dependent on the different career stages the three groups are in, but may also reflect differences in the tenor of the times in which they were educated. Both of these possible sources of differences must be kept in mind in interpreting the data. In the oldest class, those almost twenty years beyond graduation, the table shows that over 50 per-cent are in some form of management, almost equally divided between technical managers and those in non-technical areas. Another 30 per cent are staff employees of organizations, primarily performing technical functions. Only 6 per cent are in education, and the remainder are in the other professions shown. It is a distribution not unexpected from a group of M.I.T. alumni, and the class four years younger shows a very similar profile, though here the number in education has risen somewhat. In the youngest class, however, (just over ten years after graduation), more differences emerge. In this group there are even more people in education, more technical employees, and more in "other professions," The most obvious difference, the smaller number of managers, is undoubtedly due to age and level of career development. One would expect that over the next eight years many of these alumni who are presently in staff or technical positions would be promoted into management, thus approximating the distribution of managers found in the older groups. The jump in the number of professors and in "other professions," on the other hand, probably reflects a real change in initial career choices based on changing national priorities and social values. 3 The reader must be cautioned that even though the sample represents more than 60 per cent of the total population surveyed, this distribution may not reflect exactly the actual proportion of alumni in the different occupations, since we have no way of knowing whether non-response is correlated systematically with occupation. In particular, previous experience with response rates to a mail questionnaire of technology and chemistry alumni (Shuttleworth, 1940), indicate that the number unemployed as well as those employed outside the field of their training are likely to be underrepresented. -------- ·----- lm 5a TABLE 1 Basic Occupations of Alumni of the Classes of 1951, 1955, and 1959 111 Occupational Category N % 2za --- 52--- MANAGEMENT Entrepreneurs General Managers Functional Managers Technical Managers Science Engineering Computer Applications Other Fields Other Managers Family Business Other, not classifiable NON-MANAGEMENT, EMPLOYED IN COMPANY OR LABORATORY TECHNOLOGIST Science Engineering Computer Applications Other, not classifiable BUSINESS STAFF _ I 1 --. 5 N % 1951 1959 N ___ .... A__ __13Q___28_ 40 26 75 8 5 14 27 15 50 7 4 14 15 9 32 11 84 15 2 16 3 5 63 7 1 17 2 4 1 45 18 10 4 2 * _ 2 * 17 3 3 1 8 2 2 1 4 1 *k 164 30 104 27 173 39 2 108 6 4 20 1 14 '60 9 4 16 2 1 * 1 * 29 5 20 5 26 100 23 3 21 6 22 5 1 5 EDUCATION _ Consultant Engineering and Computer Applications Management and Other Architect/Planner Lawyer Doctor Other (minister, writer, artist, etc UNEMPLOYED . ._ ·~ 2 17 5 39 9 16 3 3 1 2 * 16 3 2 4 1 1 30. 3 3 7 1 1 1~__... 45___12__ 15 6 20 4 4 8 3 1 4 1 1 1 9 8 13 4 5 6 2 2 4 1 1 2 7 15 10 8 12 8 2 3' 2 2 3 2 6 1 7 2 8 2 534 TOTAL RESPONDENTS 1 13 52 --- OTHER PROFESSIONS 3 2 7 .__25 -___18 _____.8___11__ University or College Professor: Science Engineering & Computer Applications** Other Fields Junior College, High School, & Other % 100% 371 100% 446 101% ~ ~ ~ ~ *Less than 1/2% **Professors in computer applications: - --__- -________'______ 1---- 1---,,- .- I -...---. - .....---- .--.-._.. `-. --. -. -II 1951-0; 1955-2; 1959-9. __-...--,---...-.. -I-- -- . I -6- In the subsequent decade such changes led to a decided broadening of the opportunities for other kinds of careers within M.I.T. But in the sample of graduates from the 'fifties, these trends are still minimal. more is the degree of similarity across the three classes. What strikes one Here are a group of people who are fairly well established in a set of primarily managerial and technical careers. They are people who chose a particular occupational direction early in their lives and are now in the process of stabilizing it (Super, et al., 1963). The education they received, the time in which they received it, and the assumptions on which their initial career choices were made, are all reflected in the occupational roles they are now playing. The occupational distribution of Table 1 includes data on all respondents in the survey. analysis. Its level of detail, however, precludes its use for subsequent We were, therefore, faced with the problem of recombining categories in such a way as to retain the crucial distinctions, but, at the same time, to yield few enoughgtopings with a sufficient number of people in them to permit an investigation of occupational differences. Both the nature of the sample and the numbers involved guided the decisions. As a first step in this direction the three classes were combined into a single group, since the similarities between them seemed to outweigh the small differences that existed. Secondly, some categories were eliminated altogether. Law and medicine, for instance, though obviously important professions and increasingly chosen by M.I.T. graduates, represent too few people in the sample to allow meaningful analysis. For the same reason, we also ignored managers in family businesses, teachers below the college level, and the handful of respondents in other fields or not currently employed. Finally, certain categories 4 Thts is another trend that has accelerated in the ensuing time. Fully 11% of the Class of 1973 entered medical school, and 4% entered law school, in the fall following their M.I.T. graduation. 5 The 140 people eliminated in this way are included in those analyses that do not deal with occupational distinctions. _IX·_FYIIZ___I_---^-- .I LIP-I·O·I-I.·--I1·s(^-1·14(------ ... ----- - 7- were combined: computer applications were included as part of engineering and the distinction between engineering and management consultants was dropped. This process resulted in twelve occupational categories. They are given, together with their distribution, in Table 2, rearranged to reflect more accurately the degree to which they have, at the present time, a technical or scientific core. As can be seen, the entrepreneurs, general managers, functional managers, and business staff are listed together because these occupations have in common n abandonment of the primarily technical emphasis in favor of a business o- managerial emphasis. The technical managers, t working engineers and scientists, and the professors of engineering and science are grouped together because these occupations are still clearly based on a technical core. They represent the predominant part of the sample. The consultants and architects are more difficult to classify on this dimension and hence are kept separate. Career Patterns The question now arises as to whether these twelve occupational groups can be combined into a few more basic patterns. It is evident from Table 3, which gives the undergraduate major, undergraduate performance, graduate school attendance, and initial jobs of these groups, that such a patterning exists. As a matter of fact, the table indicates three groups more or less homogeneous with respect to early career events. Since the goal of the study is to investi-. gate work involvement, its origins and its correlates, in careers that can be presumed to be structurally and psychologically similar to each other, the identification of these patterns represents a first step in this process. Pattern E. Pattern E represents the predominant part of the sample. It is characterized by the following modal tendencies: 1) graduation from the School of Engineering; 2) grades below the honors level; 3) termination of education below the doctoral level; and 4) career entry through an initial ·1__· __I_ __________r_______l_ _II____·_____(__·__1 1-I1lrl-_-·1 7a TABLE 2 Final Occupational Classification N BUSINESS: NO TECHNICAL CORE 359 30% Entrepreneur 82 7% General Manager 50 4% 157 13% 70 6% 749 62% Functional Manager Business Staff OCCUPATIONS WITH A TECHNICAL CORE Technical Manager: Science Engineering 20 232 2% 19% Staff Technologist Science Engineering 60 306 .5, 25% Professor: Science Engineering 69 62 6% 5% 103 9% Consultant 60 5% Architect 43 4% OTHER OCCUPATIONS *These percentages are based on the 1211 people whose occupations fall into these categories. I III - 8- job in an engineering staff position. The occupations in which the respondents in this pattern end up comprise all of the management groups except science managers, plus business staff, consultants, and staff engineers. This is the Engineering Based Career--the various roles in which an engineer may find himself some ten to twenty years after his engineering training. The bulk of the group is still performing a clearly technical job as staff engineer or engineering manager, but for more than a third of them there has been a movement into a more business oriented career as consultant, manager, or entrepreneur. It is obvious that the business occupations in this group--and, therefore, in the sample as a whole--represent a particular type of business career, primarily that of technically trained engineers in business6 Pattern SP. The SP Pattern, representing a much smaller group, is more professionally oriented: 1) their undergraduate degrees were primarily in science (with the exception of the engineering faculty who, naturally, graduated from the School of Engineering); 2) their undergraduate grades were relatively high; 3) they tend to have doctorates; and 4) their first jobs were not characteristically in engineering staff positions. The occupations represented in this group are professors of engineering, professors of science, working scientists in industry or non-profit laboratories, and a few science managers. Though the numbers are small, it is important to point out that among technical managers., those who are science managers apparently represent a different career pattern from those who are engineering managers. The science managers seem to be a more fully professionalized group than the engineering managers. 6It must be remembered that because of the curriculum requirements of M.I.T. in the'fifties, even those with undergraduate degrees in management have had technical training. 60 . rt 0ONO 0 C Q o c H. rt ::r 0 t IM o rt W M .-. : C. *4 Z 0 ) 0 0 . - - __ - - u - _-I Z 11 M o N aQ ( -I IQ 0o4 H 1.i ., - ii 8a (I OFt tVOQ 0 Ft m (D U) J. h CD - , i 'n N O 0Z co 0, N H O Ct . O0 11 te * t-lm M H' U D MI zc C) Z zH W t: H 0C) rt Y IN DO Ha .'I N w c0 0 tD .l H z C O m C) 0 U' T% o 0 Ha N) 0% N-4 rtf It rn 0. m U) .t ct 00 L- N cn m tI m NPO o Q m 0 N1, r't1 0 0%(0 0% rt N~ 's 4 0NU N _l N m __ l 00 o N 0 I Z II 'c'IO 0 O Ft N) Ha __ , ,, __ ON .r. O .'I .'% -N4 .', I '.o 0 -j %0 Ha N N\ w 00 . 0 (A,4 I 0 N 11 co P ZII , OQ 0 0%n II 0 * 09 M f 1- 0 N It 11 co,0 0% n H 0 M I' C, 3 V C,). zcn 110Q C ) N) 0* P1 H' .M V H. o I 0 00l Il NO LA NI II Ft C 0% lhH. 0. _E - U, I .I I. N) I N" d t-h 1-h n c: F: %D U (a 0 aE O PATTERN P: ARCH/PLAN (N=43) CSi -------------------- -----·------·------ ·-------·- · ..l--..-___L__________________ U Cl) C m z t3 H III - 9 - The most interesting aspect of this pattern, however, is the fact that it includes the engineering professors. What this seems to imply is that in engineering the academic role represents quite a different path from the staff or managerial one, a distinction not found in science. This is corroborated by the differences in undergraduate cumulative grade point averages shown in Table 3. Though all the academics tend to have had higher grades than those who are now technologists or technical managers, this difference is considerably greater for engineers than for scientists. As a matter of fact, engineering professors have the highest grades of any occupational group in the sample. Undergraduate grades most likely acted as a powerful selective force for the engineering majors in our sample: if they were good, their recipients tended to go to graduate school for their doctorates which then propelled them into academic rather than industrial careers. 7 The occupations and educational backgrounds of the respondents in this pattern indicate that it can be thought of as the Scientific Professionally it presumes a doctorate, an orientation toward science, and Based Career: an orientation toward research and teaching. Pattern P. The alumni in Pattern P represent a small group of architects and planners trained specifically for their current positions while at M.I.T. They are the only group of any magnitude in the sample from what is often referred to as the "free" professions--the only representatives of the more usual Professional Career. Because of the homogeneity in career origins of the sample already described, the major "free" professions--law, medicine, theology--are almost entirely missing. 7 There is much more movement into universities from companies or labs among scientists than among engineers. If we look at all people whose first jobs were in engineering staff positions (no matter what career pattern they now fall in) only 5% are now teaching. If, in contrast, we take all those whose first jobs were in science staff positions, almost one third (29%) are now teaching in some capacity. - 10 - Preliminary Occupational Differences Some of the values and work-related attitudes and feelings associated with these patterns are discussed in future chapters. present some background to these future findings. Here, however, we want to Table 4 indicates some differences that exist among the occupations in their background, and in some of their occupational and family characteristics. The first part of the table shows the occupational status of the respondents' fathers. None of the differences are very large, but a number of things are worth noting. Looking first at the career patterns as a whole, one notes that the engineering based alumni are somewhat less likely to have had professional fathers and more likely to have had businessmen fathers, though they do not differ from the other groups at the lower end of the occupational distribution. Scientific professional alumni and architect/planners are more likely to have had professional fathers. As other occupational research has shown (Osipow, 1973), father's occupation is in general somewhat correlated with son's occupation. Within each career pattern one notes further that among the alumni who are presently entrepreneurs, there is a disproportionate number of small businessmen fathers, whereas among those who are now general managers we see a disproportionate number of fathers in major business enterprises. come from blue collar homes. Very few of the general managers Staff engineers and engineering managers are less likely to have had fathers in major businesses and more likely to have had fathers with blue collar occupations. This latter finding corroborates the idea that engineering is one of the major avenues for upward social mobility in our society. Engineering professors do not differ markedly from the staff engineers and engineering managers in fathers' background, which further supports the assertion that their different career evolution was a function of their higher grades stimulating them toward graduate school, rather than initially different career _____ III H Ft oN I oh O o ee 0 z 0 H. 0 I'd Ft 0 H m CD v I I 000> - 0 Ft 0000 0000 OCD mU (D Ft 0 CD rt H Co H E- 0. Ft D oJ TTr ot 0 CD CD co m, F-h D U) co 0 0 p)r H rt H- n O L.. o '? 0 O 03 H 10a t :r (D Pi ch cn 0 Ft 0 P, co I) rt C) r_ cV1 rt .. c oa H-axo ,>wHaN~ 1N "Q%0 = 0 -4Q l" A H ~.O oo~~~~~ H CYN . N NI Lo o H' 00 ,I H 00 l II 0% CIN H Un -,, t- ,-. = .- I O N N N " N II N 00 rt O 3 C3 r H M ca 0 O 0-. 0 00 0% O O ON - O n P tn o rZ: H OQ 1.0 U cO00 .- N N H N H N ~ N oN H Il ,-I .'I N N1 P bf IM H z: N, 0 .,I N.Q.-Uoo'o No 0 0 00 N H W Q c C *N W 'IQ N U' .I N W N N Npl H 00 NI s H C' 0A z H I 0 0 - O N 00 0N H ON % .- . Nt 0 z n H U t C <T CDE 1 cn 0 " m 0 ci loe ale8 H W 0-1 pi o I tOQ 3 H No '*1 3o I h W N N ' 02 zIInv C) N 0 0 c =1 CD 3 rt e:: n n IN0 . -I aQ N,NA Q II O C o r, 'O zZ Ln rt 4-J. H CD n N a m on P Oq Itrt ,Q O NN N n C H m P. nc rt 00 * - - 11, 1,11 = CD W U.) LI) N NN,-N -4 s 00 N INNQ o O NoI I H C Cl H H H H N H P. N '0 Nc .In N U' , N 9 = = I0 W vD \0 O O o 0 O t-n I6Q N0N N WW .1Q .1- LN o-Q NN 1.1 U It Cl) H H ' 4 H 17-- I iDH I-4 Cl)ti. -i Ro~ rH Ol) U C O. N W 4S O X.- wba " t-n I,- O o. t .n N O O o 0 00O O INQ N H H H H- H W N D NI W . oN U' N 00 o O VN O 0 Q' U' o'N 0 H U. -r O N N O NN 0 5 N8 N4 00 a U' " H -4 N NN cn Z: W 1-1-· 0)0*- HR t cl . II rt ) TA I- l I J ....... I - N N .- .Q N .) N N oN 0 Nq l-. PATTERN P: ARCH/PLAN (N=43) - C) CI H. (jQ OQ H H CD ot H _, No cc -4 0' U)I 0 l' =1 H-" 5 m H tD 0-l cI Ft CD H H- H- 03 Ft (D t tow I0 C o n- OQ 0 ID 00 CD CD i-" m 10b 0 n 0 r ' 0 C% Vi Q MQ O I - - -~~~~~~~~ * H ~ Io (P w H. O 01Q p "- _ C W -- o (0 P1 4 m o .Y n 0n 0 ,H z a t1t C rtc 0Ml r rt -- P1 = Ix: C t H. m CD ._ 0 00 N- in N1-Q .Q - H oo NoQ ZZ II0 '.0 i I I 0% c00 Ng H Oe H WL N o - o .,, 0 NI-1 H~ --4 --J N,, s m 00 NI 0 0% N z L in N a% .H H- N14 Lo -J N I., Ft 'I c-c o '*" 00 H*CD 0 CDI o o a .'e a iH ,'-4 0o 00 Vi I r § CA I1 . 0 o2 H Vie In H0 r H H H -4 0%9 N% U oD5 OQO Pe0 '.0 0 0 n V 1O . 14 a% 0 4.- c - o H -P l bn N01 Ft I- - 00 0 co l4 NP N ·-- H N ., H1 N o H !t ---- CO I " H N . ~ ~ ~ ~ - n0 Ft 'I.s O be H' t' 4'- TI N o H N a- tn oN NT Ill -J N - - - 11 I H H l N v3 H 0 cn H · r L I HH0% 4 II 0% - a s oN LA H i."" '40 III . s_ )W 0% - H i- a n QQ IZ. IV C " tn "~ Q P. o0 \0 0% co H 0 M H PH 0. Vi ale Vi 00 sa Vi LAJ .1 01H t%) '. Hj P-4 H 0% wA W _ . . N" W4 Ha cc H Vi~ NN .~~~~· " ····--- -------------- W "0% f N96 ) 0% N 014 0% HNr rn 0 N W w N I, H Nk H ae H ,Q Hw I's tM H tz C: C N 0 z I4 r CA (n -- J :: H el ----- ,-Q oR *t '.0 H 01N 0% N8 O "N ------ -J ) H 0 1N N ------ - -·-·- H PATTERN P: ARCH/PLAN (N=43) tV Ne -· -· - III - aspirations. 11 - Science professors, in contrast, have a higher proportion of fathers in the top professions as well as a higher proportion in blue collar occupations. Perhaps the academic career in science tends to draw those people whose talents are so inclined even if their socio-economic background is to some extent incongruent with it. The second part of Table 4 deals with certain current occupational characteristics. It shows, first, the sector of the economy within which the alumni are presently working--private or profit making, non-profit organizations, and national As might be expected, almost all of the Pattern E alumni or local government. work in the private sector. likely to work there. In contrast, the Pattern SP alumni are much less In the case of the professors this finding is trivial since they work in a non-profit institution by definition. But in the case of the staff scientists and science managers it represents a real difference: there is a greater tendency for them to work in non-profit or government laboratories, relative to engineering staff and managers. This part of the table also shows the income distribution of the career patterns. Looking first at Pattern E, one notes both very high incomes--the entrepreneurs, general managers, and consultants--and very low incomes--business staff and engineering staff. Alumni in Pattern SP have generally lower incomes than the Pattern E alumni, which is primarily a reflection of lower academic salaries, especially among professors of science. Engineering professors have higher salaries than science professors, but still only come even with engineering staff or managers. Staff scientists like staff engineers have very low salaries, relative to the other groups, in spite of the fact that they have a higher proportion of doctorates. Some of these differences could be due to age and career stage, but elsewhere (Bailyn and Schein, 1972) we have shown that they persist even when one controls for age. - 12 - Finally, the third part of Table 4 presents data on some current family characteristics of the alumni: 1) the stage at which their family is; 2) their wife's professional status (based mainly on level of education); and 3) their wife's working status at the time of the survey. Not surprisingly, the managerial groups are farther along in their family cycle than most other groups and professors are less far along, a reflection of the relative ages of these 8 groups. Among those who are married, the Pattern E alumni are more likely to have non-professional wives than the Pattern SP alumni, with the exception of the science managers who closely resemble the other managerial groups. The most extreme case of this is found in the general managers, among whom 88% have non-professional wives. Professors and staff scientists, in contrast, are most likely to have professional wives. The data with respect to whether or not wives are currently working show similar results. Most of the Pattern E alumni have non-working wives, with the general managers again showing this in its most extreme form; Pattern SP alumni are more likely to have working wives except for the science managers; architects tend to fall in between the other patterns except that they have the highest proportion of wives who work part time. It is obvious, therefore, that though the patterns differ from each other in terms of the occupational backgrounds of fathers, which sector of the economy they tend to work in, their income, and their present family situation, there are also clear and understandable differences on these variables among the occupations within a given pattern. Still, it is evident from the analysis pre- sented here, that some degree of patterning does exist in people's careers. On the basis of undergraduate major, undergraduate performance, graduate degree, 8It should be remembered that the trend to go into academic careers was stronger in the more recent group of graduates (Class of 1959). This class also had fewer managers, so professors are more likely to be younger than managers. I I II loarars - - 13 - first job, and present job we were able to identifyr three career patterns: Pattern E or an engineering based career, which branches into staff engineering, consulting, business staff, and management (including entrepreneurs); Pattern SP or a scientific professionally based career, which branches into being a professor, a staff scientist, or a science manager; and, finally, Pattern P, a purely professional career defined in this sample by a small number of architects and planners, which results primarily in performing in the specific profession for which one was trained. REFERENCES Bailyn, L. and E.H. Schein, 1972. "Where Are They Now and How Are They Doing?" Technology Review, 74, 3-11. Dipboye, W.J., and W.F. Anderson, 1961. "Occupational Stereotypes and Manifest Needs," Journal of Counseling Psychology, 8, 29-6-304. Hudson, L., 1967. Contrary Imaginations: A Psychological Study of the English Schoolboy, Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books. Izard, C.E., 1960. "Personality Characteristics of Engineers as Measured by the Journal of Applied Psychology, 44, 332-335. EPPS," Kolb, D., and M. Goldman, 1973. Toward a Typology of Learning Styles and Learning Environments: An Investigation of the Impact of Learning Styles and Discipline Demands on the Academic. Performance, Social Adaptation and Career Choices of MIT Seniors, Sloan School of Management Working Paper, No. 688-73. Moore, H., and S.J. Levy, 1951. Personnel, 28, 148-153. Osipow, S.H., 1973. Crofts. "Artful Contriver: A Study of Engineers," Appleton-Century- Theories of Career Development, New York: Perrucci, R., and J. Gerstl, 1969. Profession Without Community: Engineers in American Society, New York: Random House. Roberts. E.B., and H.A. Wainer, 1971. "Some Characteristics of Technical Entrepreneurs," IEEE Transactions of Engineering Management, 18, 100-109. Roe, A., 1957. "Early Determinants of Vocational Choice," Journal of Counseling Psychology, 4, 212-217. , 1961. "The Psychology of the Scientist," Science, 134, 456-459. Rosenberg, M., 1957. Occupations and Values, Glencoe, Illinois: Free Press. Schein, .E.H., 1972. The General Manager: A Profile, Distinguished Management Scholar Lecture given to the Eastern Academy of Management, Boston, Mass. , 1974. Career Anchors and Career Paths: A Panel Study of Management School Graduates, Sloan School of Management Working Paper, #707-74. Shuttleworth, F.K., 1940. Sampling Errors Involved in Incomplete Returns to Mail Questionnaires, Paper presented to the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, Pennsylvania State College, and summarized in Psychological Bulletin, 37, 437. Steiner, M., 1953. "The Search for Occupational Personalities: Rorschach Test in Industry," Personnel, 29, 335-343. The Sternberg, C., 1955. "Personality Trait Patterns of College Students Majoring in Different Fields," Psychological Monongraphs, 69, (whole #403). Super, D.E., et al., 1963. Career Development: New York: CEEB Research Monograph #4. "--s- A Self-Concept Theory, `-----