Socioeconomic Monitoring of Coos Bay District and Three Local Communities NorThweST ForeST PLaN

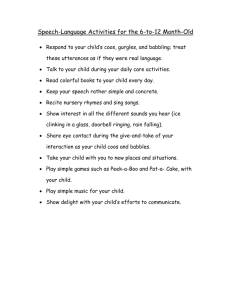

advertisement