Previous

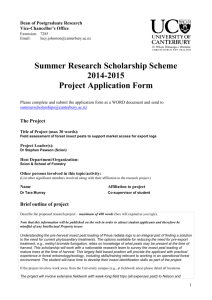

advertisement