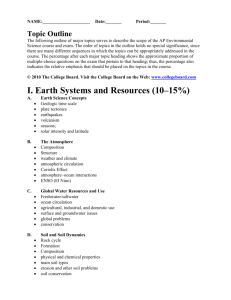

Culture and Conservation B

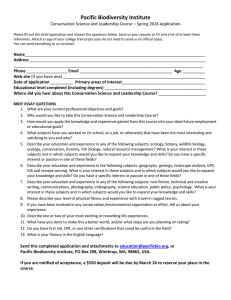

advertisement