The Marginal Economic Value of Streamflow from National Forests:

advertisement

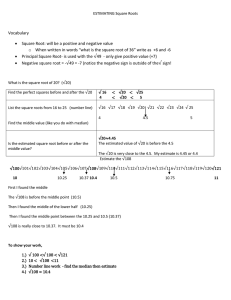

The Marginal Economic Value of Streamflow from National Forests: Evidence from Western Water Markets Thomas C. Brown U.S. Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fort Collins, Colorado Evidence from over 2,000 water market transactions that occurred in the western U.S. over the past 14 years (1990 through 2003) was examined to learn who is selling to whom and for what purpose, how much water is involved, and how much it is selling for. Roughly half of the transactions were sales of water rights; the rest were water leases. The transactions show that the price of water is highly variable both within and between western states, reflecting the localized nature of the factors that affect water prices. Ideally, if water market prices or valuation studies are to be used to help determine the marginal value of water from specific areas such as national forests, information from local markets or local studies should be used. Lacking sitespecific value information, only rough estimates are possible. Keywords: water value, streamflow, economic value, water markets INTRODUCTION The economic value of a good or service is indicated by a willingness to sacrifice other goods and services in order to obtain or retain it, and is typically measured in money terms, usually as willingness to pay (WTP). WTP may be determined for changes in the quantity, quality, or timing of water. This paper deals with the value associated with water quantity, specifically the quantity of streamflow. The value of a small change is what economists call marginal value. Estimates of marginal value are useful in analyzing policies that cause relatively small changes, such as changes in streamflow resulting from vegetation management. Of course, even small changes in streamflow may have numerous additive downstream effects. For example, an acre-foot of streamflow increase may first be used by recreationists, next pass through a hydroelectric plant, then be diverted to a farm, and finally be diverted to a city, all the while helping to dilute wastes and enhance fish habitat. The aggregate value of a change in streamflow is equal to the sum of its values in the different instream and offstream uses to which the water is put during its journey to the sea (e.g., Brown et al. 1990). For the general case, the aggregate value of a small change in streamflow (V*) is given by: M Furniss, C Clifton, and K Ronnenberg, eds., 2007. Advancing the Fundamental Sciences: Proceedings of the Forest Service National Earth Sciences Conference, San Diego, CA, 18-22 October 2004, PNWGTR-689, Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. where i indicates a water diversion or instream use location; αi is the proportion of the marginal acre-foot that reaches a use i (water that is not consumed upstream) (α ≤ 1); βi is the proportion of the marginal acre-foot reaching use i that arrives when it actually can be of use (β ≤ 1); and Vi is the value of the marginal acre-foot in use i assuming the water is put to use (V ≥ 0). The task of estimating the marginal value of streamflow from a national forest thus consists of estimating the Vs and their respective αs and βs. Our focus here is on Vi. There are two basic approaches to estimating the marginal value of water: employing economic valuation methods and observing water market prices. The suite of valuation methods (Gibbons 1986; Young 1996) was developed because markets for goods like water were uncommon and, when present, rarely competitive. However, water market activity has increased in recent years, raising hopes that water markets can offer useful estimates of water value. This paper presents evidence from water market transactions in the western United States. To review how price is related to marginal value, consider the case of offstream uses depicted in Figure 1. If demand (i.e., marginal WTP) for water at a point of use is represented by D, Q1 is the total quantity of streamflow available, and P1 is the cost of transporting (e.g., pumping) the diverted water to the point of use, then users desire to divert Q2 units. Here the net marginal value of the diverted streamflow (V) is P1-P1 = 0 per unit. Alternatively, if water supply were constrained at Q3, Q3 units would be diverted. At a diversion of Q3 units, the marginal value of delivered water is P2, and V = P2-P1. If a competitive market for streamflow existed in this location, the market price would be P1, and if a competitive market for delivered water existed its market price would be P2. BROWN This example thus illustrates two points: (1) streamflow has value at the margin only when there is not enough of it to meet all demands; and (2) if the price includes consideration for storage or delivery, it may overstate the marginal value of streamflow. Figure 1. Marginal value of offstream diversion. WATER MARKETS Water has become scarcer as population, economic growth, and changing values in the West have increased demand for water (Gillilan and Brown 1997). Where institutions allowed it and transaction costs were not excessive, the growing scarcity often brought willing buyers and sellers together in what is called a water market. The term “water market” lacks a precise definition, but once a few voluntary trades of water of relatively common physical and legal characteristics occur, it is said that a water market has developed. Water markets require a well-administered system of transferable water rights. The doctrine of prior appropriation that underlies water law across the West allows for clearly defined and transferable water rights, and state agencies or the courts administer and enforce those rights, although the states differ in how they implement the doctrine and administer the water rights systems (National Research Council 1992). Water market activity may be limited by physical and legal constraints. Physical constraints on water trades, such as uneven water availability and lack of access, are eased by such structures as diversion dams, canals, and storage reservoirs, which extend spatial and temporal control over water delivery. Legal constraints on water sales often exist, perhaps due to state law (e.g., constraints on moving water to another basin, or constraints on the availability of instream flow rights) or federal guidelines for specific water development projects. As scarcity has intensified, some constraints on water markets are being loosened (North 1990; Loomis 1992). 459 If water in a water short area were freely traded in an efficient market, water would be reallocated via trades to the point where each user was consuming at the point where the marginal values in all uses were identical (e.g., the marginal value in irrigation would be equal to the marginal value in municipal use or in instream recreation). In this ideal world, a single market price would emerge that would indicate the marginal value of raw water in that market area. However, in the real world, even in those locations where water markets exist, water rarely trades so easily or completely. Two reasons for this are lack of a homogeneous product and lack of market competitiveness. Lack of homogeneity is a natural consequence of how the prior appropriation doctrine accommodates the stochastic nature of streamflow. The doctrine deals with shortage by assigning priorities to water rights and temporarily canceling permission to divert based on those priorities, beginning with the most junior right and moving as far up the list of priorities as needed to assure delivery to more senior rights. Each individual right may have a unique priority date. Senior rights are worth more than junior rights because senior rights face less risk of shortage. If each right is unique, homogeneity of product is compromised. However, within the overall structure of prior appropriation there exists a quite different approach know as fractional flow rights (Eheart and Lyon 1983). With such rights, all users have equal priority, and shortage is accommodated in a given time period by lowering the allowable diversion for all users. The use of fractional flow rights is common in mutual ditch companies and some water conservancy districts, wherein water is owned as shares of the total amount available (Hartman and Seastone 1970). Within such an organization all members essentially have the same priority, and the effect of a flow increase available to the organization is distributed to the members in proportion to the number of shares each owns, thus providing homogeneity of product. Many of the more active water markets deal in shares of such a company or district. A fundamental tenet of neoclassical economic theory is that competitive markets yield prices that reflect the true marginal economic value of the good being traded. Competitive markets have many buyers and sellers, do not artificially restrict price or ability to trade, have low transaction costs, allow an easy flow of information about prices and potential trades, and internalize all relevant costs and benefits of the transaction. Water markets typically fall short on one or more of these requirements. Many markets areas are so small that sellers and buyers are few. In others, laws, regulations, or customs limit price. In many water markets transaction costs are substantial, involving 460 MARGINAL ECONOMIC VALUE OF STREAMFLOW administrative and legal requirements. In many markets information is not readily available. And externalities (effects on individuals not party to the exchange) commonly exist, especially in the form of changes in water quality and instream flow (Howe et al. 1986; Saliba 1987). Some of these restrictions on the competitiveness of the market (e.g., a limited number of sellers) may elevate the price relative to the price that would be established in a purely competitive market, whereas others tend to depress the price (e.g., government subsidies, transaction costs, regulations or customs). Many of the restrictions, such as transaction costs, will also tend to limit the number of trades. Studies of water markets have usually focused in detail on one or a few specific markets (e.g., Hartman and Seastone 1970; Saliba et al. 1987; Michelsen 1994; Howe and Goemans 2003). Only with a detailed examination can the numerous characteristics of the individual markets be given their due consideration. This study, in contrast, takes a broad look across the western United States, emphasizing geographical scope rather than in-depth focus (see also Brown 2006). This “big picture” approach offers a look at how water prices in general have changed over the past few years and how they differ across locations or across the purposes for which the water was purchased. When water is sold in the West, either a water right changes hands or use of the right is essentially leased for a period of time. Ownership of a water right conveys access to a specified quantity of water in perpetuity, subject to particulars such as priority, timing, and location. With a water “lease” as used herein, the holder of the right agrees to deliver, or allow the buyer access to, a certain quantity of water over a stated time period, subject to conditions such as timing of access and location. One-time transfers of water (essentially short-term leases) are sometimes called “spot market” trades or “rental” transactions. This paper reports on both sales and leases of water rights. METHODS The broad-scale examination of water prices reported here is made possible by the Water Strategist and its predecessor the Water Intelligence Monthly, published by Stratecon, Inc., of Claremont, California, which have summarized many of the available western water market transactions in reports released on a monthly or quarterly basis. Fourteen years of transactions reported by these publications (1990-2003) were tabulated to provide the estimates of the price of water described here. It is important to note that these publications did not report on all the transactions that occurred. Especially in the case of water leases, large numbers of trades were not summarized. Neither are the included transactions a random sample. Thus, the current report indicates the nature, but not the breadth or precise character of western water trades. Each water transaction entry in the Water Strategist or Water Intelligence Monthly briefly summarizes one or more actual trades. The entries do not allow a full understanding of what influenced the price, and are not always consistent in how the transactions are described (perhaps because some information was not available). Nevertheless, most of the entries provide sufficient information for a rudimentary analysis of the factors influencing water market prices, and together they form the most comprehensive set of information available about water market trades in the western United States. The entries typically include buyer, seller, purpose for which the water was purchased, type of transaction (whether purchase or lease of a water right), and the source of the water (surface water, ground water, effluent, or potable water). Buyers and sellers are categorized herein as one of the following: (1) municipality; (2) irrigator (farmer or rancher); (3) private environmental protection entity (e.g., public trust concern, or private entity such as the Nature Conservancy); (4) private entity providing water to many users, such as a water “district,” “association,” or “company,” referred to here as a “water district”; (5) public agency (federal or state government agency, conservancy district, or other water “authority”); (6) other entity (e.g., power company, mining company, developer, investor, country club, feedlot, individual homeowner); or (7) several entities (when several buyers or sellers of different types were listed, such that the transaction could not be neatly assigned to one of the other categories. The purpose of the transaction was characterized as one of the following: (1) municipal or domestic (including commercial and industrial if serviced by a municipality, and golf courses and other landscape irrigation); (2) agricultural irrigation; (3) environmental (e.g., instream flow augmentation); (4) other (e.g., thermoelectric cooling, recreation, mining, aquifer recharge, augmentation of flows leaving the state per court order, supply to individual businesses such as feedlot or manufacturing plant, an investment of undefined characteristics, unspecified); or (5) several (several purposes, such that the transaction could not be neatly assigned to one of the other categories). Some entries covered several related transactions. For example, several sellers or several buyers, or both, may have been included in the entry. Or several transactions within the same market may have been listed together in the same entry. Such entries were broken down into separate cases for analysis if distinct prices were listed and different categories BROWN 461 Figure 2. Trends in total number of acre-feet transferred . of buyers, sellers, or purposes were involved. After this disaggregation process, a total of 2,447 transactions were available for the 1990-2003 period. The Colorado Big Thompson (CBT) market is the most active market for water rights in the West, with up to 30 or more purchases per quarter by municipalities alone. It is also a market about which market information is readily available. The entries listed 949 CBT trades over the 14 years. Because the sale price for CBT shares differed little among trades completed during a given month, and because the volumes traded were typically small (averaging 40 acre-feet), all CBT transactions of a single purpose within a given month were tabulated as one case for analysis in order to avoid having CBT transactions overwhelm the summary statistics. This aggregation process left a total of 228 CBT cases for the 14-year period, and thus a total of 1,726 cases (2,447 - 721 CBT transactions consolidated) for analysis. Of these 1,726 cases, 349 were omitted from further analysis because key information was missing (such as price or amount of water transferred), something other than raw water (i.e., effluent or treated water) was involved, the price included payment for things other than water (e.g., land), or the transaction was not a market sale (e.g., it was an exchange or a donation). Thus, 1,377 qualifying cases (1,726 - 349 missing information) were left for analysis. Figure 2 shows the total water volume by year of the qualifying cases and the full set of cases. Prices, expressed on a per acre-foot basis, were adjusted to year 2003 dollars using the consumer price index. Prices for water rights were converted to an annual basis using a 3% interest rate, which is approximately the mean annual growth rate in real gross domestic product over the past 20 years in the U.S. Although mean prices are also reported, this analysis emphasizes median prices, which more accurately indicate the price of a typical water sale when the price distributions are skewed. Prices paid for untreated water often include reimbursement for water management, including such services as storage and conveyance, in addition to the cost of the raw water in the stream. Such prices are analogous to P2 in Figure 1 given supply at Q3. Because our primary interest is in the value of streamflow, costs of water management were not included in the price when such costs could be separated out. However, storage and delivery services are so commonly a part of water transactions that such services were often not even mentioned in the entries. Most prices reported here probably include some consideration for the value of water management services. RESULTS All results reported here are based on the 1,377 cases meeting the criteria for further analysis explained above. Figure 3 shows the number of cases by a convenient geographic breakdown, climatic division (www.cdc.noaa.gov). Fourteen states have qualifying cases (all states in Figure 3 except North Dakota, South Dakota, and Nebraska). Three climatic divisions within these states have over 75 cases: division 4 in northeast Colorado, including Denver, Fort Collins, and other cities along the northern Front Range; division 5 in California, capturing the southern (San Joaquin River) portion of the Central Valley and on down to the Bakersfield area; and division 10 at the southern tip of Texas, along the Rio Grande as it enters the Gulf near Brownsville. Nine climatic divisions had between 26 and 75 cases-three in California, two in Texas, and one each in Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, and Nevada. Thirteen climatic divisions had between 11 and 25 cases, and 43 had from 1 to 10 cases. Another 44 climatic divisions in the 14 states had no cases. 462 MARGINAL ECONOMIC VALUE OF STREAMFLOW Figure 3. Number of cases meeting criteria for analysis of market prices, 1990-2003, by climatic division (divisions are numbered independently within each state). Quantity of Water Sold A median of 804 acre-feet was transferred per case (the mean is 17,234 acre-feet). Table 1 lists the volume transferred by state. Three states (Arizona, California, and Idaho) account for 75% of the water transferred. In all years much more water has been transferred via leases than via rights (Figure 4), which reflects in part the fact that water transfers are easier to agree upon and arrange on a temporary than on a permanent basis. The median lease size over the 14 years is 6000 acre-feet per Table 1. Western water market activity and prices by state, 1990-2003 (both Arizona leases and rights, price in California year 2003 dollars per acreColorado foot per year). Idaho Kansas Montana New Mexico Nevada Oklahoma Oregon Texas Utah * Cases with a $0 price were Washington not included. $0 indicates Wyoming rounding of a very low price. All case, compared with 110 acre-feet for water rights cases. There is considerable annual variation in amount of water transferred for both types of transactions, but no apparent relation between the two trends (R = 0.13). Ten percent (141) of the cases involve groundwater, with the remainder (1,236) being of surface water. However, only 4% of the water transferred in these trades has been ground water, as suggested by the fact that the average water volumes per case are 6,679 acre-feet for groundwater and 18,438 for surface water. Number of cases Volume (N) (1000 acre-feet) 86 294 427 64 16 5 59 69 3 43 207 43 25 36 1,377 7,910 8,104 443 2,802 11 15 525 1,299 81 261 1,376 122 563 219 23,731 Mean 51 96 133 15 40 20 77 125 246 31 104 34 70 37 96 Price Median Min* 48 66 81 6 48 6 55 106 118 9 28 16 32 40 56 0 0 1 0 13 2 1 6 46 1 7 5 3 3 0 Max 115 1,000 630 251 54 56 607 375 575 302 2,258 165 343 93 2,258 BROWN 463 Figure 4. Trends in total quantity of water transferred (qualifying cases only). Price of Water A quick look at Table 1 reveals at least three findings of interest about water prices. First, mean prices exceed median prices for the complete set of cases (a mean of $96 per acre-foot per year versus a median of $56) and for all but two states. Second, the range in price is substantial for each state, with most minimums near $0 and maximums typically in the $100s (the maximum of $2,258 is for a lease by a mining company). Clearly, water changes hands at a variety of prices. Third, the median prices vary substantially among the states, ranging from below $10 in Idaho and Oregon to over $80 in Colorado and Nevada (ignoring Oklahoma and Montana because of their small numbers of cases). There is no apparent relation between number of cases and median price. Also of note is that water trades are much more common in some states (e.g., California and Colorado) than others (e.g., Montana and Oklahoma). Water scarcity no doubt plays some role in determining the number of trades, but institutional and legal differences are probably the most important factors affecting sale frequency among the western states. To begin to understand the reasons for the range of median prices, consider Table 2, which summarizes the sales by type of transaction, either a lease or a perpetual right. Over all states, the median price for leases ($47 per acre-foot per year) is about two-thirds that of rights ($72) given the 3% interest rate for annualizing prices of rights. However, the median price of leases exceeds the median annualized price of rights in most states. The overall superiority of median water rights prices results largely from the fact that 56% of the water rights cases are for Colorado, a state where the median price of water rights far exceeded the median price of leases. Fully 216 (59%) of the 369 water rights cases for Colorado are of CBT shares, and another 129 (35%) are for other water rights along the northern Front Range within or near the area of the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District where CBT shares trade (in climate division 4, Figure 3). Also of interest is that for 10 of the 14 states the number of lease cases exceeded the number of rights cases. The exceptionally high number of water rights transactions in Colorado reflects the relative ease with which such transactions can be accomplished and the strong demand for secure water supplies by the fast-growing cities along the Front Range. Table 3 summarizes the cases by the purpose for which the water was purchased. Over half (739) of the purchases were for municipal purposes, another 23% (321) were for irrigation, and 11% (150) were for environmental purposes. The median price paid for municipal uses ($77) Table 2. Western water market prices by state and type of transaction, 1990-2003 (year 2003 dollars per acre-foot per year). Leases Median N ($) Arizona California Colorado Idaho Kansas Montana New Mexico Nevada Oklahoma Oregon Texas Utah Washington Wyoming All 48 250 58 49 11 5 29 4 2 34 159 11 21 34 715 58 68 18 8 50 6 55 83 347 9 29 7 37 40 47 Rights Median N ($) 38 44 369 15 5 0 30 65 1 9 48 32 4 2 662 40 37 84 3 16 76 109 46 7 24 17 13 43 72 464 MARGINAL ECONOMIC VALUE OF STREAMFLOW Table 3. Western water market prices by purpose of buyer, 1990-2003 (both leases and rights, year 2003 dollars per acrefoot per year). Purpose Municipal Irrigation Environment Other Several All N 739 321 150 105 62 1377 Mean Median ($) ($) 118 46 56 180 51 96 77 28 40 62 56 56 Min ($)# Max ($) 0 1 0 2 2 0 1607 490 450 2258 190 2258 # Cases with a $0 price were not included. $0 indicates rounding of a very low price. was nearly three times that paid for irrigation water ($28) and nearly twice that paid for environmental purposes ($40). Purchases for municipal purposes tended to be of water rights (453 cases involving rights versus 286 for leases), suggesting that municipalities desire-and are able to pay for-dependability of supply. Purchases for irrigation and environmental purposes tended to be of leases. For the three principal purposes for which water was purchased (municipal supply, irrigation, and environmental protection), there is a wide range in median price across the states (Table 4). The overall median price paid for municipal water ($77 per acre-foot per year) is heavily influenced by sales in Colorado, where the median price of the 250 cases is $88. Other states with both high median Table 4. Western water market prices by state and purpose of buyer, 1990-2003 (both leases and rights, year 2003 dollars per acre-foot per year). Municipal Median N ($) Arizona California Colorado Idaho Kansas Montana New Mexico Nevada Oklahoma Oregon Texas Utah Washington Wyoming All 47 149 250 5 14 0 26 59 3 0 141 28 3 14 739 48 96 88 6 48 77 110 118 26 20 40 77 77 Irrigation Environmental Median Median N ($) N ($) 12 66 110 31 2 1 4 0 0 20 40 13 5 17 321 45 45 72 4 51 6 50 8 24 7 17 5 28 5 51 19 19 0 3 10 7 0 19 0 2 15 0 150 45 64 20 8 2 47 43 26 40 32 40 prices for municipal purposes and a substantial number of cases are California (median of $96), Nevada ($110), and Wyoming ($77). Excepting Colorado, the median price of the remaining 489 sales for municipal purposes is $57. The overall median price paid for irrigation water ($28) is also heavily influenced by Colorado, which had over one-third of these cases and a median price of $72. Other states with a substantial number of cases include California (median of $45), Idaho ($4), and Texas ($24). Excepting Colorado, the median price of the remaining 211 cases for irrigation purposes is $16. Among purchases for environmental purposes, states with the highest median prices and with at least ten cases are California ($64), Colorado ($20), Idaho ($8), Oregon ($26), and Washington ($32). Who Sold to Whom, and for What Purpose? Irrigators are the sellers in 38% (531) of the cases (Table 5), not counting when they might appear among the 222 cases involving several sellers. Public agencies are the sellers for another 16% (224) of the cases. These public agency sales include those involving State Water Project or Central Valley Project water in California, Central Arizona Project water in Arizona, and water managed by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in many states, including Colorado, Oregon, and Wyoming. Nearly all public agency sales were leases. Municipalities were the most common buyers of water, accounting for 27% (375) of the cases (Table 5), not counting when they might appear among the 206 cases involving several buyers. Other active buyers were public agencies with 17% (234) of the cases, farmers with 15% (204) of the cases, and water districts with 13% (183) of the cases. Trends in Occurrence and Price The number of cases per year (across all states and purposes) ranges from a minimum of 77 in 1995 to a maximum of 142 in 1999 (Figure 5). Recent years show an increase in the number of cases (over the 14 year period, the four highest numbers of cases occurred in 1999, 2001, 2002, and 2003); the overall increasing trend is statistically significant at the 0.05 probability level based on the MannKendall test for time trends (test statistic = k = 2.56). Examining sales of leases and rights separately reveals that the number of leases has increased substantially over the past 14 years (k = 3.60), whereas the numbers of sales of rights show no trend (k = -0.49). The median price per year (across all states and purposes) ranges from $34 in 1998 to $76 in 1991 (Figure 5). No overall trend is evident (k = 0.24). However, looking BROWN 465 Table 5. Number of western water market trades from seller to buyer, 1990-2003 (both leases and rights). Seller Buyer Municipality Irrigation Environmental Municipality Irrigator Environmental Water district Public agency Other Several Total 26 175 1 21 39 60 53 375 8 96 0 19 48 12 21 204 0 10 1 1 1 1 0 14 Total Water district Public agency Other Several 7 60 0 38 32 26 20 183 18 95 1 32 46 22 20 234 6 40 0 8 18 68 21 161 4 55 0 16 40 4 87 206 69 531 3 135 224 193 222 1377 Figure 5. Trend in median price of water, all water uses (includes both leases and rights, year 2003 dollars). separately at sales of leases and rights reveals that the median price of rights has increased significantly (k = 2.07), whereas the price of leases has not (k = 0.00). Colorado, especially the Front Range area, is largely responsible for the overall increase in the price of water rights. Price Differences Across Markets Space constraints preclude presenting details here about individual water markets. An analysis of separate markets revealed the following findings. First, prices at a given time can vary considerably even among markets located quite close to each other. Such markets often differ in local economic conditions, availability of alternative supplies (such as groundwater as a supplement for surface water), extent of water distribution infrastructure, and past decisions to obtain secure surface water rights. Second, prices in competitive markets can change dramatically over time in response to development pressures or weather cycles. Third, prices of leases in many markets are heavily influenced by administrative criteria, and thus not competitively set (exceptions to this observation include the Texas Rio Grande lease market). Fourth, water rights are typically sold in relatively competitive situations where the prices are determined by individual negotiations between buyer and seller. CONCLUSIONS Analysis of the trades reported by Stratecon allows the following general statements (which may not represent the full population of western trades): 1. The incidence of water market trades is geographically variable. Markets are very active in a few areas of the West, but most areas apparently had few trades over the past 14 years. Although three states (California, Colorado, and Texas) account for three-fourths of the qualifying sales, even in these states some areas had very few trades. 2. In a given year, at least ten times as much water changes hands via leases as changes hands via sales of water rights. The median size of leases is over 50 times that of water rights sales. 466 MARGINAL ECONOMIC VALUE OF STREAMFLOW 3. Across the western states, the median price of water is highly variable, with Colorado and Nevada having the highest medians, and Idaho and Oregon having the lowest medians, when sales of leases and rights are combined. However, the price of water is also highly variable within every state, reflecting the particular physical and legal characteristics of individual water markets. This variability makes it risky to transfer a value from one location to another, thus complicating the process of benefit transfer. 4. Among the major purposes for which water was purchased, purchases for municipal uses have the highest median price ($77) and account for over half of all trades. Purchases for agricultural irrigation and environmental protection have lower median prices (roughly $35). 5. Purchases for municipal purposes have tended to be of water rights, whereas purchases for irrigation, environmental, or other purposes have tended to be of leases. 6. Irrigators were the sellers in about 40% of the transactions. Public agencies, such as federal agencies managing large water storage and delivery projects, were the sellers in another 16% or so of the transactions. Municipalities were the most common buyers, accounting for about 30% of the transactions. Other common buyers were farmers, public agencies, and water districts. 7. Across all cases, the median price of leases in real terms showed no consistent trend over the past 14 years, whereas the median price of water rights showed an upward trend. Water market activity in aggregate offers a broad and rich understanding of the value of water. Water values can be substantial, but because they also are highly variable both geographically and temporarily, care must be used in applying water market prices to analyze policies affecting streamflow. Acknowledgement: Alex Bujak, research assistant with Colorado State University, ably helped summarize the transactions and maintain the database. LITERATURE CITED Brown, TC. 2006. Trends in water market activity and price in the western United States. Water Resources Research 42, WO9402, doi: 10.1029/2005WR004180. Brown, TC, BL Harding, and EA Payton. 1990. Marginal economic value of streamflow: A case study for the Colorado River Basin. Water Resources Research 26(12): 2845-2859. Eheart, JW, and RM Lyon. 1983. Alternative structures for water rights markets. Water Resources Research 19(4): 887-894. Gibbons, DC. 1986. The economic value of water. Washington, D.C.: Resources for the Future. Gillilan, DM, and TC Brown. 1997. Instream flow protection: Seeking a balance in western water use. Washington, DC: Island Press. Hartman, LM, and D Seastone. 1970. Water transfers: Economic efficiency and alternative institutions. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press. Howe, CW, and C Goemans. 2003. Water transfers and their impacts: Lessons from three Colorado water markets. Journal of the American Water Resources Association 39(5): 1055-1065. Howe, CW, DR Schurmeier, and WDJ Shaw. 1986. Innovations in water management: Lessons from the Colorado-Big Thompson Project and Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District. In: KD Frederick (ed.), Scarce water and institutional change. Washington, D.C.: Resources for the Future: 171-200. Loomis, JB. 1992. The 1991 State of California Water Bank: Water marketing takes a quantum leap. Rivers 3(2): 129-134. Michelsen, AM. 1994. Administrative, institutional, and structural characteristics of an active water market. Water Resources Bulletin 30(6): 971-982. National Research Council. 1992. Water transfers in the West: efficiency, equity, and the environment. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. North, DC. 1990. Institutions, institutional change, and economic performance. New York: Cambridge University Press. Saliba, BC. 1987. Do water markets “work”? Market transfers and trade-offs in the southwestern states. Water Resources Research 23(7): 1113-1122. Saliba, BC, DB Bush, and WE Martin. 1987. Water marketing in the Southwest--can market prices be used to evaluate water supply augmentation projects?, General Technical Report RM-144. Fort Collins, CO: USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station,. Young, RA. 1996. Measuring economic benefits for water investments and policies, Technical Paper 338. Washington, DC: World Bank.