Issues in the Philosophical Foundations

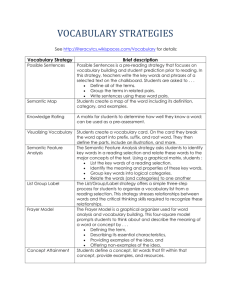

advertisement