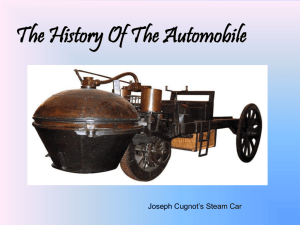

Future of the Automobile Program

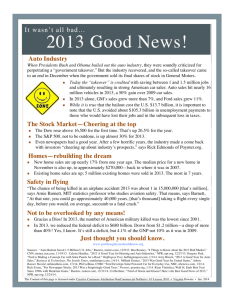

advertisement