US Support for REDD+: Reflections on the Past and Future Outlook

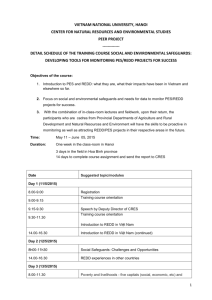

advertisement