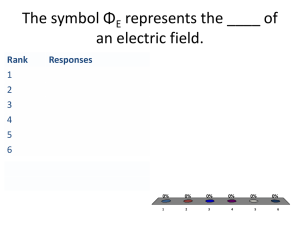

USE for the Graduate Bachelor of

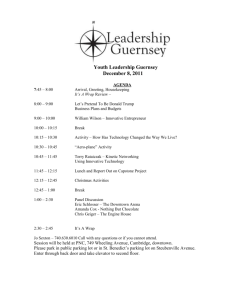

advertisement