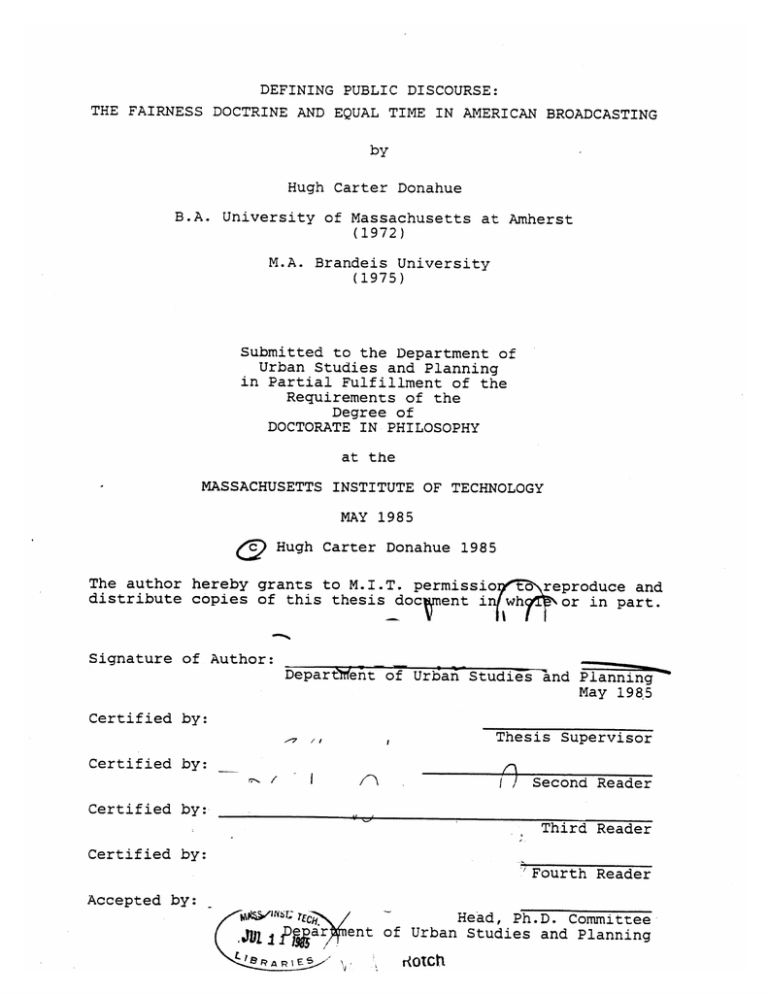

PUBLIC AND EQUAL Hugh Carter Donahue

advertisement