LATIN AMERICA SOCIO-RELIGIOUS STUDIES PROGRAM (PROLADES)

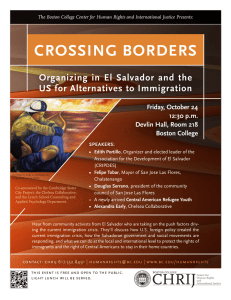

advertisement