F ARMSCAPING

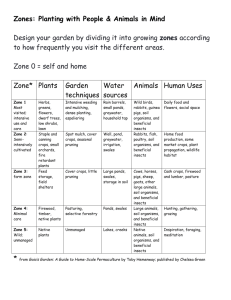

advertisement