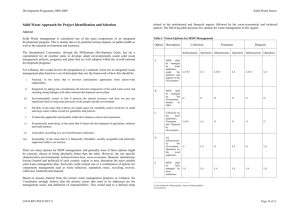

The Community Choice Between Resource Recovery

advertisement