Susan R. Diamond B. Sc. Stanford University J.D.

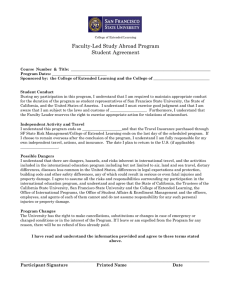

advertisement