AND CHRISTINE L. ROBERTS

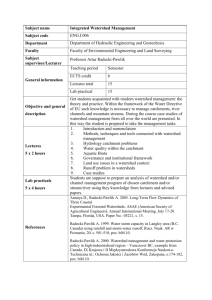

advertisement