Document 11282042

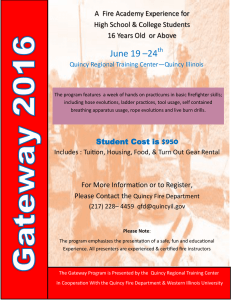

advertisement