IMMINENCE AND IMMANENCE: by J.

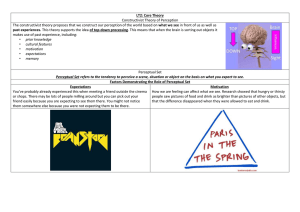

advertisement