SCHOOLS IN COMMUNITY EMPOWERMENT: SCHOOL G. DONATO

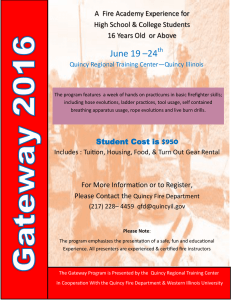

advertisement