The Structure that Builds the Movement

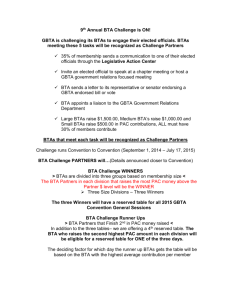

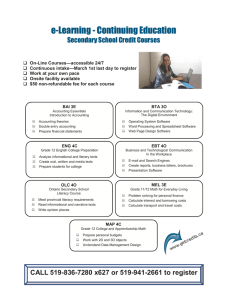

advertisement