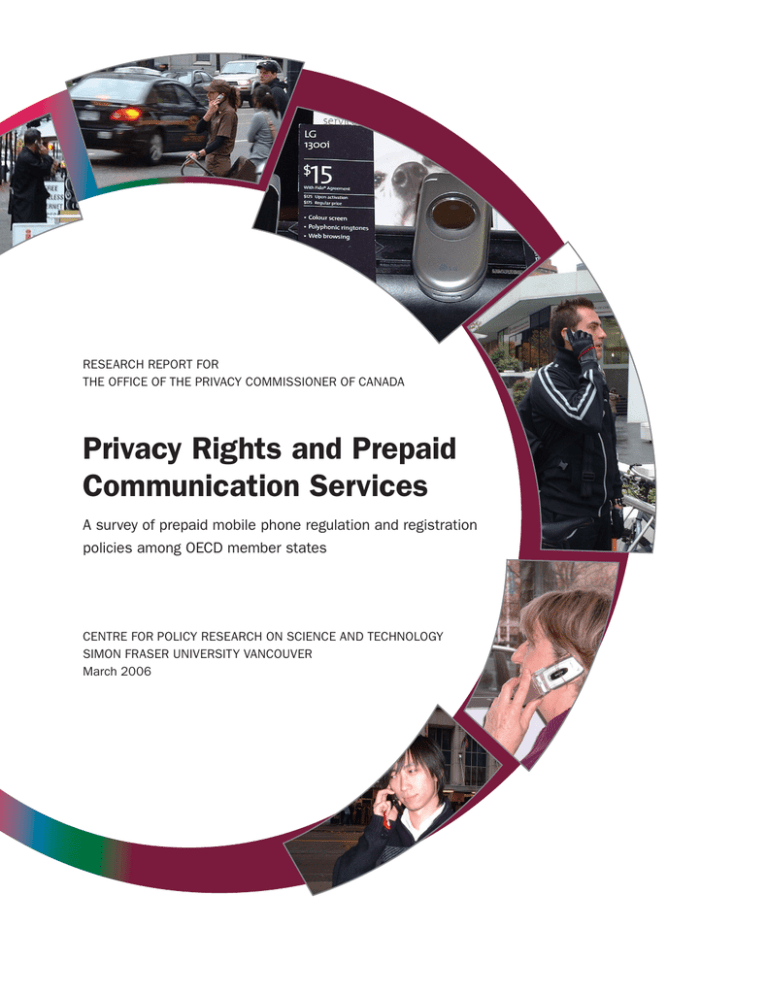

Privacy Rights and Prepaid Communication Services policies among OECD member states

advertisement