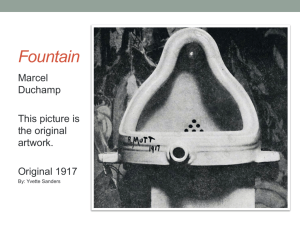

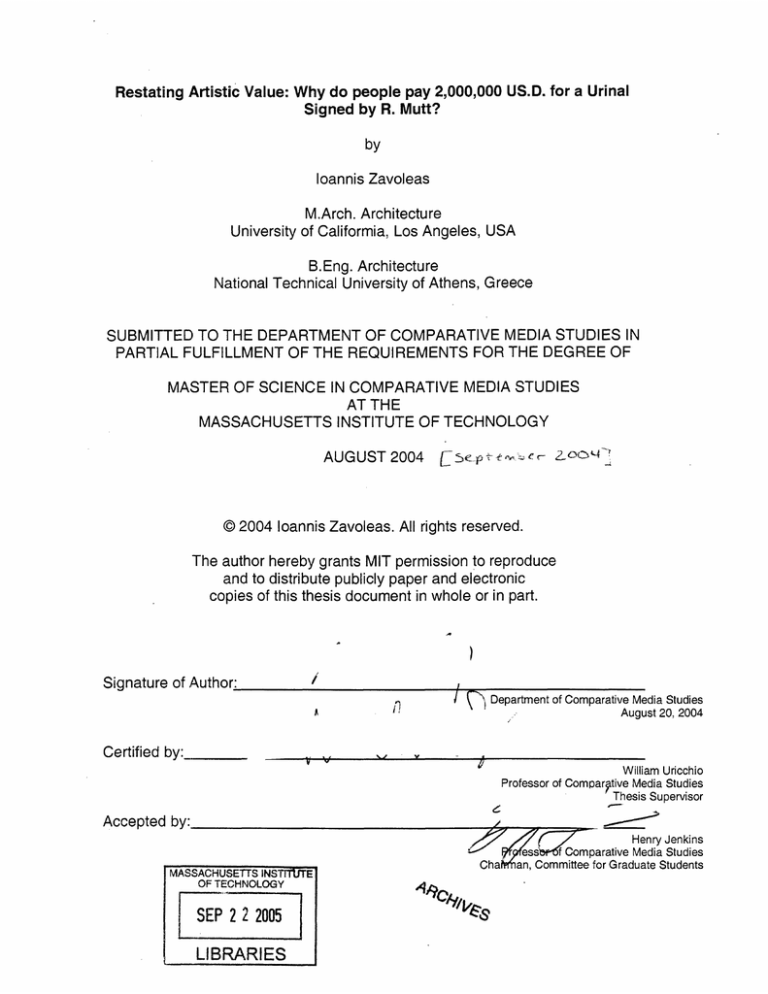

Restating Artistic Value: Why do ... Signed by R. Mutt?

advertisement