GAO VOLUNTARY ORGANIZATIONS FEMA Should More

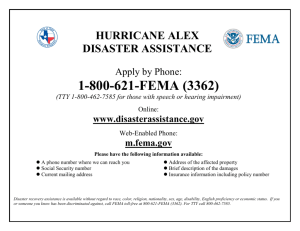

advertisement